By Ira Kantor

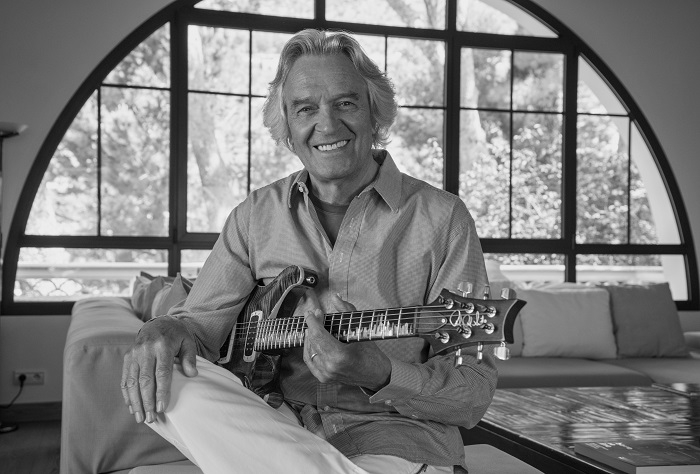

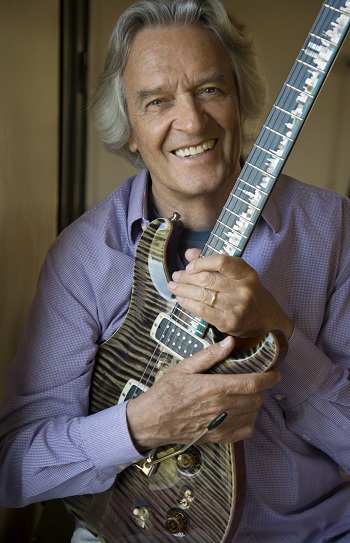

In advance of his new album, Black Light (read our review here), fusion legend John McLaughlin took time to speak with Elmore from the little village of Cap-d’Ail in the south of France about the musicians who helped inspire several of the album’s “homage tracks,” the state of the record industry and why he gels so well with the guys in his band, the 4th Dimension.

Elmore: Your new album kicks off with “Here Come the Jiis,” an homage to your prior band, Shakti. Who are the Jiis and who specifically is this track paying tribute to?

John McLaughlin: It’s one of a number of pieces on the album that’s in a way a kind of an homage to departed friends, to departed colleagues whom I love and miss. “Here Come the Jiis” refers to the young mandolin player in the Shakti group with whom I played for 14 years (Uppalapu “Mandolin” Shrinivas) and who we lost last year at the tender age of 45 of liver failure. It was really a tragic death. He was a brilliant, wonderful musician and human being, a prodigy playing concerts since he’s seven years old.

“Jiis” is plural because when the band would meet—and I’m talking about the Shakti band here—Shrinivas would always arrive with the percussion player. They’d walk in and everybody would say, “Here come the Jiis! We’re delighted to see you.” I tried to say “Here Come the Ji”—it just didn’t work. I’m so used to saying after all these years, “Here come the Jiis” and it’s really both of them.

But in my heart it’s really the homage to Shrinivas, who was one of the greatest musicians I’ve ever played with really. He was such a joyful, funny person. We had more laughs than I can count. And the tune was like that. It’s a very joyful tune. It’s up-tempo, bright, sunny, with a lot of percussion going on. That’s how I remember Shrinivas.

See below for the exclusive premiere of “Here Come the Jiis”:

EM: Another track, “Gaza City,” seems a bit more somber. Is it a commentary on ongoing conflicts in that region that have occurred for years?

JM: Absolutely. You’re right on the mark. With my wife, we’ve been supporting this particular NGO (non-governmental organization) in Ramallah, Palestine for the last ten years. To make a long story short, it’s an NGO that uses music therapy to heal traumatized children, and adults too for that matter. So I’ve been over there a couple of times—not for concerts, charity concerts, because nobody has any money over there—but just solidarity concerts and it was really the bombardment of Gaza City last year that still upsets me, frankly.

Of course what is known is we’re not going to change the world. But as a musician and as an artist, this is my reaction to it. It’s kind of a melancholic tune, isn’t it? I was there last spring before the summer bombardment and it’s not exactly how people see it on TV.

EM: You also have a tribute to the late Paco de Lucia on the album. What did he mean to you personally and musically over the years?

JM: Well, let me rewind real quick back to 1978 or late 1977, around that time. I was in Paris, in somebody’s car, and I was listening to the radio and all of a sudden this track from Paco came on. I had never heard of Paco de Lucia in ’78. Anyway, I listened to the end of the piece and they said, that was Paco de Lucia. “I’ve got to meet this guy,” I thought, because I should remind you that when I was 14 years old, I discovered flamenco music. I used to skip school and hitchhike down to Manchester so I could see and hear flamenco guitar players. I actually wanted to be a flamenco guitar player because I fell in love with that music.

But you need a teacher and in the village where I was living, I mean they had never even heard of flamenco. So in the end, I got caught by jazz, but the love of flamenco never left me. In particular it was Miles Davis who caught me. When I heard these two particular albums he made—Miles Ahead and Sketches of Spain—in which he so elegantly expressed his own particular love of the Hispanic traditions, I really felt I was in good company here.

In any event, I was lucky because Paco was in Paris at that same time. I found out where he was and I said, listen, you are amazing and I don’t want to just make a record with you; I want us to work together and do something. So we sat down, we jammed and he said, let’s do it. I said, well, if we get another guitar player, we’ll have a lot of variation. So I got Larry Coryell. Larry came in and we started touring towards the end of ’78. We did two major tours of Europe at that time. Until that time, Larry had some personal issues he really had to deal with and it just wasn’t working out. And Paco suggested Al Di Meola, since they’d already collaborated. So that was the guitar trio.

Subsequently, Paco and I became very close. He was really like a brother to me. As a human being, he was exceptional. And you know what the title “El Hombre Que Sabia” [on Black Light] means? It means “The Man Who Knew.” It’s not that he knew something; he just knew. He was a marvelous inspiration.

So let’s fast forward to the beginning of last year. We’d been thinking about recording. (Incidentally, we did a tour in the ’80s and there’s a recording that’s going to be coming out of one of the concerts at Montreux early next year finally. I just finished the mix on that. I’m thrilled about that.) We got a number of pieces together for a recording and, just before he left for Central America, he died, on the 25th of February. I had just sent him this piece now retitled “El Hombre Que Sabia” and he was particularly fond of this tune. He was really happy that we were going to record together, of course.

After he died, I started finally working on this record. I said, I got to find a way to just show how much I love him and miss him. And this tune that he was fond of, I rearranged it for the band and I think it came out very well. I mean, it was really written for two guitarists, but it is such a tribute to the guys in the band. They approached it with such sensitivity. They did a great job.

That’s Paco to me. I could talk for an hour just about the impact he’s had on me.

EM: Will other collaboration tracks with Paco de Lucia come out in some way? Or is there other music from your collaborations yet to be released?

JM: Well, I know there was a recording made in Berlin, maybe, and we’re going back a long time here. There were a number of video and audio recordings made during that particular tour and because it was Montreux—I’ve been going to Montreux for over 40 years now. It’s taken me 28 years to convince them to put it out. Finally they sent me the stereo track and said, well, see what you can do; can you just polish it up and make it ready. That’s finished now. There’s got to be some other things somewhere. I don’t know where they are and maybe they’ll kind of come out of the closet or maybe they’re waiting for me to die [laughs]. That’s some dark humor.

EM: Knowing you worked with the late drumming great Tony Williams in various groups, is there a Tony Williams/Lifetime vibe going on throughout this album?

JM: Tony has had an impact on me since 1963, when he did one of his first records with Miles: In Europe. He blew my mind. I loved Miles since ’58 when I first discovered him. I listened to Miles with Philly Joe Jones and Jimmy Cobb and then Tony came in Miles’ band and he just blew me away. When I joined Miles’ band in January ’69, it was a dream come true.

Tony revolutionized the way drummers play. He played it like a true musical instrument, not just keeping the beat. Today I see how drummers are just keeping the beat and I’m thinking I would be bored out of my brain. The guy’s got something to say. You got to let the drummer be free, you know. Tony of course was the epitome of freedom because when he didn’t want to play—in the middle of a tune, if he didn’t feel it—he’d stop playing. Miles loved him. Miles loved Tony more than anything. He said Tony was it. Nobody has ever played like Tony before or since.

EM: This is your third studio album with the 4th Dimension. What is it about this particular group of musicians that resonates so strongly with you?

JM: What is it? Oh man, you know, there’s a certain kind of chemistry since Ranjit joined the band because Gary has been with me since the onset—I’d say about 11 years ago, when we first started just putting it together. Etienne has been with me about six, seven years now. And Ranjit’s been with me about three years even though we’ve been associated with other projects in the past. In the past three years or so, there’s a special kind of complicity that has developed between all of us; when I get with the band, I’m thrilled and the music is joyful. It’s not that often where you get a band that comes together and everybody’s just thrilled to be there, you know what I mean?

We’ve already played hundreds of concerts. We go down to Australia in about one month and then up through Asia (see full tour schedule here) and I’m talking to the guys and they’re saying, “I can’t wait, man! I can’t wait!” So I’m saying, “Me too! Me too!” I’m just biting at the bit; I want to start playing.

That vibe goes into the music. To me, actually, that’s how it should be in every formation. I see some jazz groups and I don’t know whether they’re just trying to be cool and it’s like, wait a minute, who cares about cool? I mean, where’s your passion? What do you feel? You know, I want you to blow me away. If I’m in an audience and I listen to a band, I want them to just sweep me away into their world with the passion and joy that’s coming through their music so that I lose myself in their music. That’s all I want and I know I’m just like everybody else. Everybody who goes to a concert wants to be captured one way or another, but the only way you can capture somebody is if you got the complicity with the musicians and the love and affection. I know I sound like a hippie but I’m an old hippie anyway.

The music’s missing its raison d’etre, as they say in French: its reason to be. Music is the festival of life. It’s a celebration of life at this moment because tomorrow, who knows if we’re even going to be here tomorrow. Yesterday’s gone. The only time we have—especially when we’re playing—we know how beautiful this very moment is and that brings us to reality. Music is a voice of the collective spirit. Even if we don’t know it, we’re all connected to it and music shows us that and everybody speaks music because everybody understands music. And they know when it’s happening and they know when it’s not happening.

Of course, we all have bad nights; I know all of us individually, collectively, have. But that’s not for the want of dedication because these guys, their whole lives have been dedicated to music, like mine. I’m 73 years old. I started playing music when I was eight. I started playing guitar at 11. I’ve been playing guitar for 62 years, man, and I cannot wait to start so what does that tell you?

I am personally thrilled with this record because, in a way, it’s related to an album that goes back about ten years called Industrial Zen, where I started to introduce some more colors from sound design and just bring a kind of a portal where the music changes direction all of a sudden or changes direction and breathes before it comes back to the head, before we start playing. This combination of live playing with these kind of colors, you can only do in the studio. This is not a live album work but I’m very happy the way it turned out.

EM: What are your hopes for the new album?

JM: You know, I’ve given up expectations about how people will enjoy it because you never know. There’s two kinds of success: one is the musical kind and the other is the commercial—and it’s rare when the two meet, isn’t it? Anyway, I haven’t made any money from recordings for about ten years, but, from the beginning, I was never making records for money. You make records because you have to. I’m like a painter; I have to paint. So if we can recoup what we’ve invested in this record, I’m a happy guy because there is no record industry left, frankly. What am I going to do? Am I going to stop recording? No, of course not. I’m not in it to make money. I do it because I have to. It’s my life.

I believe that people will enjoy this record because it’s got these vibes inside of it and the players are great. I mean they’re kicking my ass too. I mean, they’re on top of me. I’ve got to pull all this stuff now just to keep up with these guys but isn’t it wonderful. I’m giving a little bit too; I’m not just taking because they need a little provocation too. So I’m doing my bit for them because they want it too. We all need that. We all need that kind of little kick in the butt just to move along and keep playing and I think people who like this kind of music will feel the vibes, will feel the love and the affection and admiration in it. I certainly hope so anyway.

EM: Any final thoughts?

JM: I’m just very grateful for the opportunity to speak to you because without the possibility of speaking to people like yourself, who’s going to know I recorded, you know what I mean? No one’s going to know. We have our little label. The only artists on the big labels are the singers these days. It’s really rough for the young instrumentalists today. I’m just happy to have a chance to chat with you because people like to know what’s going on in the heads of musicians and why they do what they do or how they do what they do. To have an opportunity makes me very grateful, so, really, thank you. I really appreciate it.

[…] profiled McLaughlin and premiered the lead track, “Here Come the Jiis.” The story & music Here. The composition is described by McLaughlin as “one of a number of pieces on the album […]