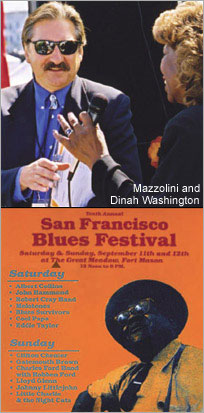

“I book the festival for me,” says Tom Mazzolini, founder and producer of the San Francisco Blues Festival, the longest running blues festival in the United States. It’s common for blues industry people to move from somewhere else to Chicago to follow their passion. Mazzolini did just the reverse. In 1963 he moved from Chicago to Pasadena, and then to San Francisco in ’65 to complete his college education. He has an American history degree from San Francisco State.

“It all pretty much started for me in the early ’60s here in San Francisco, going to some of the neighborhood clubs and to the Fillmore. That was it, and also I was reading some of the various publications at that time like Singout, and when Rolling Stone started, they were doing a fair amount of blues things.”

“It all pretty much started for me in the early ’60s here in San Francisco, going to some of the neighborhood clubs and to the Fillmore. That was it, and also I was reading some of the various publications at that time like Singout, and when Rolling Stone started, they were doing a fair amount of blues things.”

Soon, Mazzolini was writing blues obituaries for Rolling Stone on people like Sleepy John Estes and L.C. “Good Rockin'” Robinson. He did a Howlin’ Wolf obituary for City Magazine, owned by Francis Ford Coppola, and eventually became a contributing editor to Living Blues for 12 years in the ’70s and ’80s. The man who produced this, the 33rd annual San Francisco Blues Festival, has truly become a renaissance man.

Winner of the W. C. Handy Award as blues producer, Mazzolini’s credits also include curator of the San Francisco’s first major art exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Rental Gallery, board member of the Blues Foundation’s International Advisory Committee, and stage productions producer for the San Francisco Art Festival. He’s the host of the Bay Area’s longest running blues show on KPFAFM in Berkeley, where he’s interviewed such blues legends as Jimmy Reed, Otis Rush and Lowell Fulson.

THE PSYCHEDELIC GENERATION GETS THE BLUES

The high profile psychedelic rock movement in The Bay Area in the ’60s was more folk driven than blues driven, according to Mazzolini. In fact, it was Mike Bloomfield of the Butterfield Blues Band who turned on Bill Graham, the man who booked the Fillmore to post-war electric blues in the mid-’60s. Nick Gravenites of the Butterfield Blues Band and now of The Chicago Blues Reunion underlines Mazzolini’s observations. “When Paul Butterfield played the Fillmore West at the very beginning, Bill Graham went up to Mike Bloomfield and told him he was the greatest guitar player in the world. Mike’s comeback? ‘You should hear the people I learned from.’ (B.B. King, Albert King, Freddie King, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and so on). Bill Graham asked, ‘Who are these people? Are they around any more?’ Mike Bloomfield gave Bill Graham their booking agents’ phone numbers and that was start of bringing the black blues artists out of the chitlin circuit into the white hippie audience, and that was start of the crossover of blues.”

By 1969, the music business was leaving blues behind. “Graham was told by a lot of the emerging megarock groups in the late ’60s and early ’70s that they wanted to dictate the billing,” says Mazzolini. “Therefore, they determined who was going to be on the show with them, and they didn’t want any blues acts on the show. That started a downward slide. Rock was really branching out into different arenas, and the blues-based  styles were becoming less popular. So, rock and roll as it developed from folk-rock around here and in L.A. went into psychedelic, and then into the various other styles of music, and blues began to disappear. When that happened, I couldn’t go anywhere to find acts anymore and to hear that music. So, that was the impetus for me to start the first (San Francisco Blues) Festival.

styles were becoming less popular. So, rock and roll as it developed from folk-rock around here and in L.A. went into psychedelic, and then into the various other styles of music, and blues began to disappear. When that happened, I couldn’t go anywhere to find acts anymore and to hear that music. So, that was the impetus for me to start the first (San Francisco Blues) Festival.

“My goal really was to find anybody that Bob Geddins had recorded that was still alive or who made recordings in the ’40s and ’50s and to try and get them on stage at the festival.” Geddins was an African-American from Waco, Texas who had recorded all the locals from earlier decades. Mazzolini describes him as “the Sam Phillips of the West Coast.” Sam Phillips didn’t have enough money to release Elvis Presley and Howlin’Wolf records nationally on his Sun label, so he sold or licensed their recordings he made in Memphis to labels like RCA, in Presley’s case, and Chess with Howlin’ Wolf.”Geddins did the same thing. He sold the masters to Aladdin, to Chess, and to various other L.A. labels because he never had the money to really get the stuff out there,” says Mazzolini. Among the local artists Geddins had recorded were: Johnny Fuller, Tiny Powell, Jimmy Wilson, Lafayette Thomas, Johnny Hartsman, Jimmy McCracklin and a young Lowell Fulson who would go to become the most important blues man on the West Coast scene prior to the psychedelic era.

LOWELL FULSON DEFINES THE SCENE

“Then, Lowell Fulson moved to Los Angeles where he began his residency there recording for Chess. He had all those hits like “Talking Bells,” “Reconsider, Baby” and all those tunes. But Lowell really came out of San Francisco. So, those guys were playing a style of blues that was west coast.”

The defense industry recruited African Americans from Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas and Oklahoma for the shipyards and other defense locations. Although it can be said as a generality that none of the blues people were originally from The Bay Area and there was no common sound, there was a larger jump and be-bop influence here than in the other blues centers around the country.

“There was a heavy Texas influence, a lot of T-Bone Walker influence and a lot of Charles Brown. Mike McCracklin would eventually end up recording for Imperial and expanding his base and then eventually went on to Stax, but he and Lowell were probably among the most successful. So, these guys had never played with the others (who were moving in from Chicago), and when they came together at the San Francisco Blues Festival, that’s how the whole thing came together.”

Be the first to comment!