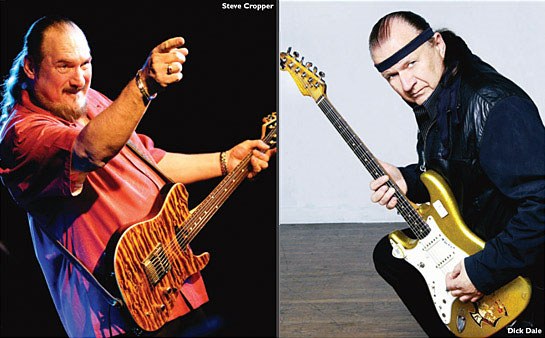

STEVE CROPPER

Steve Cropper was born on October 21, 1941 in Dora, Missouri, where country music dominated the airwaves. Fortunately for soul fans, his family moved to Memphis when he was nine, where he was exposed to gospel, R&B and early rock ‘n’ roll.

At 14 he bought his first guitar, and formed the Royal Spades, in honor of the “5” Royales and their guitar player, Lowman Pauling. The Royal Spades later reformed as the Mar-Keys, and recorded an album including the hit single “Last Night,” for Satellite Records, which later became Stax.

Cropper left the Mar-Keys during their first tour, joined Stax as a producer, engineer and songwriter, and his career really took off.

In 1962, Cropper, along with Booker T. Jones and others, was asked to play a studio session. After the session was over the band continued to play, and Stax co-owner Jim Stewart wisely turned on a recorder. They recorded a second side which became known as “Green Onions.” The track became a Number One hit, and Booker T. & the MG’s became Stax’s house band, playing for Otis Redding, Eddie Floyd, Albert King, Carla Thomas and many more, also recording several successful albums of their own.

As a songwriter, Cropper helped pen hits like “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay,” “In the Midnight Hour” and “Knock on Wood.” He produced and played on a seemingly endless series of Stax hits and was listed by Rolling Stone as one of the 100 all-time greatest guitarists.

Cropper left Stax in 1970 to start his own recording studio, Trans-Maximus, where he worked with artists like Jeff Beck, John Prine and Tower of Power. He and fellow Stax alumni Donald “Duck” Dunn joined Levon Helm’s RCO All-Stars, before being contacted by John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd about working on music for a Saturday Night Live skit called the Blues Brothers. The ensuing band ended up recording three albums, the Number One hit “Briefcase Full of Blues,” and a hit movie.

In the early 1980s Cropper turned his attention to his solo career, recording the albums Playin’ My Thang and Night After Night.

He has recently worked on albums by Ringo Starr, Paul Simon, Buddy Guy and Johnny Lang, in addition to remaining an active member of the Blues Brothers Band, which tours regularly. In 2008, Cropper and Felix Cavaliere of the Rascals released an album called Nudge It Up a Notch, on the revitalized Stax Records imprint. He currently runs his own studio, Play It, Steve! Records.

DICK DALE

Dick Dale, the father of surf music, is also one of the forefathers of heavy metal. His music is featured in Quentin Tarantino films and Disneyland rides. Dale, among other interests, is an avid surfer and martial arts student who beat cancer and got right back to touring.

Born May 4, 1937, in Boston, Massachusetts, Richard Monsour grew up steeped in the traditional folk music of his Polish mother and Lebanese father, and used that education to become one of the first guitarists to break away from Western scales. Dale’s legendary loud and fast playing stemmed from his desire to recreate Gene Krupa’s drumming on the guitar.

The Monsours moved to southern California in 1954, where, at the suggestion of a local country music DJ, Richard took the stage name Dick Dale. The selftaught, left-handed guitarist recorded the locally distributed song “Ooh-Whee Marie.”

Dale became a serious surfer, and tried to recreate surfing sounds in his music. In 1961, he released the single “Let’s Go Trippin’,” the first recorded surf rock song, and reopened the Rendezvous Ballroom with the first permit to perform rock ‘n’ roll music, though the surfer audience was forced to wear ties, which Dale and his band the Del-Tones handed out before the show.

Dale’s status as the father of heavy metal began with his association with Leo Fender. Fender asked Dale to try out his new guitar, the Stratocaster. Dale kept blowing the speakers and amplifiers, sometimes sending them out in flames. Fender, Dale and the JBL speaker company worked together to create amps and speakers that could stand up to Dale’s heavy playing, and rock music was thrust into a new era.

Another defining moment in the creation of surf music came when Dale decided he was unhappy with his singing voice’s lack of vibrato, and with the way his guitar’s notes sounded against it. He pulled the reverb unit out of a Hammond organ and asked Fender to make one for his guitar. He plugged his microphone into the ensuing Fender Tank Reverb, liked the way it made his voice sound, and later plugged his guitar into it, creating his signature sound.

Dale studied martial arts, cared for endangered animals, took up environmental activism after nearly losing his leg from a pollution-induced infection while surfing, and became an advocate for cancer patients after being diagnosed with the disease in 1966. Even when not touring or recording regularly, his music continued to have an influence. His hit song “Miserlou” was featured in Pulp Fiction, and he recorded original material for Disneyland’s Space Mountain.

In 1986, Dale began touring again, and continues to perform today. Fender has just begun production of a revolutionary acoustic guitar, a Dick Dale design.

![]()

Elmore: What are you listening to right now?

Steve Cropper: Something that I thought was new, to find out that it’s not that new but it’s new to me: Ray LaMontagne. I picked him up on a Travelers’ commercial watching a golf tournament

Dick Dale: I love listening to Israel Kamakawiwo’ole. He was like Elvis Presley, and what a voice. I’ve always loved Hawaiian music. I love the harmonies. I love to hear Frank Sinatra, he’s a phraseist. He’ll spend three days learning to say the word “love” so that it will sound a certain way. I’m a hopeless romantic.

EM: What was the first record you ever bought?

EM: What was the first record you ever bought?

SC: I think it was Ruth Brown “Oh What a Dream.” I wanted to buy a version of Bill Doggett’s “Honky Tonk” ’cause a friend of mine, Duck Dunn, our bass player with the MG’s, had the record.

DD: I never did buy a record. The only guitar player that I ever heard was my dad’s records. I listened to Les Paul & Mary Ford when they did “How High the Moon.” And then Patti Page, Doris Day. You gotta understand, I did not choose to be a musician/performer—my dad pushed me into it.

EM: Where do you buy your music?

SC: Usually on iTunes. I bought ’em up in Sam Goodys and wherever they had CDs, but when they discontinued those, it made it more difficult. I’m still one of the old school guys, I prefer to buy a CD, put it in a CD player, put on my headphones and listen to it, and skip over or back up or do whatever I want to do. I have not learned—I’m just lazy—how to use an iPod. I usually listen to music in the car, by myself, when I can turn it up, blast it, hear it the way I like it. I don’t listen to a whole lot of music at home.

DD: I get CDs and they give me all that stuff. I don’t go into a record store. I won’t even leave the damned boat to get food. Days will go by in the goddamned port. I’m always busy doing something that has nothing to do with music. I never practice and I never rehearse, only time I rehearse anything is when I gotta break in a new guy.

EM: What was the first instrument you played?

SC: To actually bang on, probably piano, my grandmother’s, and then I kind of fiddled around with my uncle’s guitar for awhile; he was a piano player and a fiddle player but he had a guitar. He used to let me get it out of the closet. I wouldn’t say strummin’ on it ’cause I hadn’t learned to do that yet; I pulled on the strings when I was about ten or eleven.

DD: I used to bang on my mother’s canister set listening to Harry James and Gene Krupa records. I would listen to the records that my dad had and bang on cans. He used to beat the crap out of me, because during the Depression days, you just didn’t go out and buy things. I worked for five cents an hour in an Arabic bakery, gas was 12 cents a gallon, you could go to a movie for ten cents.

I’d spend my summers with my grandma and grandpa. I used to listen to my Auntie Wanda play on the piano at my grandma’s house, and they had one of those pump pianos, with the rollers and stuff. So I began loving the piano. I went to take a piano lesson at home, and nobody had a piano so they gave me this cardboard piano keyboard and said, “put your fingers on it.” I thought, What the shit? The hell with that. But every time we went to my grandmother’s I’d play on the piano.

Then my uncle gave me a trumpet. I took a trumpet lesson and didn’t like it—I wanted to play what I wanted to play. So I started playing either Louis Armstrong or Harry James.

I was reading the back of a Superman magazine. It said, sell so many jars of Noxzema skin cream and send us the money and we’ll send you this ukulele that has a cowboy on a horse rearing with a lariat. Because I always wanted to be a cowboy singer, I went out in the snow and banged on doors selling Noxzema and I waited about four months and I finally got it and it was nothing but pressed cardboard and the pegs would fall out, so I smashed it. I took my little red wagon with my Pepsi and Coca-Cola bottles and got six dollars and bought this ukulele for $5.96, a plastic ukulele, brown on the bottom and cream on top. I got this book and it said, put your finger here, put your finger here, I played upside down and backwards because the book never said “Turn it the other way, stupid, if you’re left handed.”

And I learned on a ukulele and I couldn’t understand why my fingers wouldn’t go. I never looked at somebody else playing, because it didn’t help. My buddy said, “I can’t tell you how to do it, but I’ll tell you where your fingers are supposed to go.”

EM: What brought you to the instrument you now play?

SC: I realized I wanted a guitar the summer I was 14—other than meeting girls, you see guys on TV playing guitar and that seemed to be a cool thing to do. There was an older guy, Ed Bruce, and I saw him on a talent show one morning, a little assembly on the last Friday of each month. This guy came up, had an electric guitar, plugged it into his amp, just him by himself and played the song “Bo Diddley” and I was mesmerized. That was it, that’s all I wanted to do, was learn how to play “Bo Diddley.”

I bought my first guitar, and I worked during the summer to save money. My dad said, “We can’t afford it.” I found a cheap one in Sears, in those days called Sears and Roebuck. I thumbed through the catalog and found a Silvertone. I shined shoes and mowed yards, set bowling pins at a bowling alley and did whatever jobs I could do, saved $17 and ordered one. When I got it I didn’t know how to string it; I had to find somebody that knew how.

DD: For the longest time in my life I played ukulele chords. Me and my buddy Lester would go walking out into the swamp to take the swamp berries. My grandmother made the best blueberry turnovers in the world. We heard these guys strumming in the woods and followed the sound to this old shack. It was just like Deliverance.There were about five guys in there, they had their cigarettes rolled up in their shirts and I go, “Look at those guitars.” A round-holed guitar, acoustic. “I’m selling it.” “Oh, really, now much?” “Eight bucks.” “Oh wow, can I make payments?” So I made payments. I tried to do 25 cents a week, but he wouldn’t go for it. I gave him 50 cents a week to get my first guitar, in the seventh grade.

I said, “Wow, look at all those strings. What am I going to do?” He said, “Just play ukulele chords on it.” So I went to play ukulele chords, and that sounds pretty good until you hit the last two strings. So I said, “What am I going to do?” And he said, “Well, just don’t play those two strings on the bottom.” And I used a Gene Krupa strumming style of picking. That’s how I play the guitar, like I’m playing drums.

EM: Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

SC: Most of my old buddies are gone. If there was any kind of market for something Eddie Floyd and I might write, you know I’d call him in a New York second. Of the artists I’ve never worked with, my number one answer has always been Tina Turner. She is somebody that I respected and loved her music and never did get a chance to work with.

DD: I can’t even read music, so I really fooled them. I don’t even know what an augmented 9th or a 13th is. I just bang on the guitar. I just make it scream with pain or pleasure, and that’s basically it. I got off the piano because if I write on the piano—well I don’t write, I just make it up—but, then I play it on the guitar and it takes on a different picture, a different connotation.

EM: What musician influenced you most?

SC: Lowman Pauling, the leader, guitar player of the “5” Royales. He wrote a lot of songs that other people covered and got credit for, like “Dedicated To The One I Love,” God, what a great song! They were a very legit, very honest gospel group that tested the waters with pop, made a couple of records for King Records and then one day decided—I don’t know if they called it the Devil’s music—just went back to gospel and they’ve been there ever since. Hank Ballard & the Midnighters, and of course any musician that grew up in the late ’50s and ’60s was influenced by Ray Charles, had to be, if you were into blues. I think the rule of thumb is stay true to yourself, don’t try to venture out too much and for sure don’t start copying somebody else, ’cause that will always jump up and grab you. It’s better to be creative and just be true to yourself and have fun with it.

DD: Who influenced me was Hank Williams, Gene Krupa and Harry James.

|

Dick Dale & His Del-Tones

Surfer’s Choice l (Sundazed)

This is Dick Dale’s 1962 debut album, with bonus tracks. Known as “The King of the Surf Guitar,” his influence reaches way beyond surf music. The album notes claim that “he birthed the genre single-handedly” which sounds icky, and we all know it’s not true, but there is something so original here, we’ll let it slide. Seemingly whiter than white, nonetheless Dale—outrageous for 1962—had a real knowledge of the blues, which he used as a secret weapon. Actually this album is very different from the later stuff, in that his voice is rough, more soulful, and arrogant, almost like he was from the Bronx. Almost? black. I guess Columbia cleaned THAT up real fast. Try “Night Owl.” There is a weird combination of sophistication and ignorance here; well it’s 1962, innit? On “Fanny Mae,” the harp guy knows his instrument, but it seems he don’t know blues harp. But throughout there is this wild, scorching guitar—try “Jungle Fever.” Face it, this guy is real. The Beatles sure show his influence, and everyone loves his “Miserlou.” This album is arguably the seed from which all of West Coast Rock sprang. Just ask Jimi Hendrix. —Robin the Hammer

|

EM: What was the song or event when you realized you wanted to be in music?

SC: We were so into music when we were in high school, that’s really all we did. We put the Mar-Keys together in high school, and our main goal was to have a good dance band. We were very fortunate with the song called “Last Night.”

If you want to look at it technically, it was the first actual “Twist” instrumental. [sings] “Come on baby, let’s do the twist,” it had the “Twist” beat, but there was no lyric on it, and boy, the disc jockeys wore that thing out. Just out of high school, I really didn’t like being on the road. I liked being in the studio making music and being at home, so I quit the Mar-Keys and the road, went back to work in the studio, got my old job back at the record shop and started doing odd things, met Booker, and lo and behold the following year we put together Booker T. & the MG’s and had a big hit record with “Green Onions,” and that thing’s still living on today.

DD: My dad pushed me up on stage. This was how he tricked me. In a contest in like seventh grade, my father says, “You’re going on up there. This kid wants you to back him up.” I go, “I don’t know what to do.” And he goes, “Just back him up. Just strum your ukulele chords like that, and he’s going to play.” And then the kid says to me, “Okay, I’m going to do this, Dick, can you do that?” I said, “You know what? That sounds kind of simple. Why don’t you go like this?” And he goes, “You do it and I’ll strum.” So I started doing it and right in the middle of the damned song, he gets up and walks off the stage. He left me. It was all planned. I never backed down from anything in my life, so I just stood there and played. I came in second place and that was that.

If I get a hair or something up my ass, I just pick up my guitar to try something, because it’s in my head. But mostly they just sit. When I get through performing they are packed away and I never touch them again until I perform again. The only thing I might sit down and do is if I walk by the piano, sit down there and play something on it and do things like that.

And that’s basically what my whole life is. It’s total instability. What the hell.

EM: Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

SC: I’d have to have two singers, Tina Turner and Otis Redding, and I certainly would like Ike Turner in there somewhere because I love his guitar playing and I love his piano playing, so he can cover a lot of space. My drummer would have to be the greatest R&B drummer, Al Jackson, one of the greatest drummers period, the greatest I ever worked with. I’d be slighting my buddies if I didn’t take them along, it’d have to be Al, Booker and Duck. That’s to me the greatest musicians on the planet. I’d rather be sitting in the audience myself. If they ask me to sit in I might get up, but I don’t look at myself that way. There’s so many great guitar players to pick from I’m not even sure I’d hold up.

I like to use horns, and if they’re gonna play, make a lick that everybody can remember. Don’t just play ’cause you’re up there, play something people are going to remember, that’s what makes it work. Same thing with studio work on a guitar, don’t just play ’cause you got one in your hand, play something that people are going to walk out humming.

DD: Well of course, if he was alive, I’d have Hank Williams. I’d have Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. I’d have Vince Gill. If it wasn’t my son Jimmy on drums, it would be Prairie Prince, who gave Jimmy his drumsticks. He’s the greatest—he’s so on the money and he’s such a person. It’s one thing to be able to play, but it’s another thing to be a person, and they don’t come any better than him. Nokie Edwards of the Ventures, and Chris Isaak’s bass player, Roly Salley, and Harry James.

EM: What’s your desert island CD?

SC: I’m an individual song guy, I’d have to put together an album of all different songs. An Otis Redding album, and it wouldn’t matter which one it was. I want to say Ray Charles or Stevie Wonder or all this other stuff, but I think when it all came down, I could listen to Sam Cooke for the rest of my life. I always said that if you took Sam Cooke and Little Richard and put them in a jar, shook it and poured it out, you’d get Otis Redding. In his ballads he could croon like Sam Cooke and in his uptempos he could wail like Little Richard, so he had the best of both worlds.

DD: They’d be romantic songs, no matter what. Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra or some music of Hawaii. Maybe Patsy Cline—I’d put the CD in my car and cry all the way to my destination. ![]()

Be the first to comment!