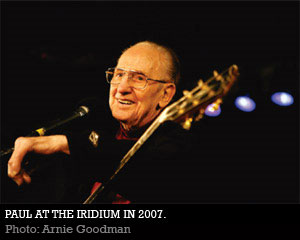

In the film Chasing Sound!, about legendary musician and inventor Les Paul, the performer, celebrating his 92nd birthday at the Iridium Jazz Club in New York City, calls a woman out of the crowd to join him on stage and sing a rousing version of “Route 66.” The moment came as no surprise to his band, or to the woman, Sonya Hensley, who had been introduced to him a few years earlier.

“I met a pianist who was coming in to play with Les, and he invited me for my birthday, and he told Les, ‘Hey, she’s a singer,’ ” Hensley said. “And Les said, ‘Oh, really? Well, I’m going to call you up, okay? You can either sink or swim, honey.’ Those were his first words to me, so I picked a couple of songs I thought he would like, and forget it, it was on.”

Paul’s contribution to music transcended his hit songs, millions of records sold and countless imitators spawned. He relentlessly pursued new sounds, and when the sounds he wanted could not be made, he broke through technological walls to make them happen. That tireless drive created the modern recording industry and landed Paul in the Inventors Hall of Fame, the New Jersey Hall of Fame and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The Wizard of Waukesha, the father of the electric guitar, Paul came out of a mini-retirement in 1983 to play a weekly spot at Fat Tuesday’s, a small Manhattan jazz club, then later moved his show to the Iridium Jazz Club, a small, basement room, now wedged between Mamma Mia! and Ellen’s Stardust Diner in Times Square, a return to the intimate clubs that launched his career. He played his spot right up to his death, on August 12, 2009, at the age of 94, when it was taken over by a series of guest guitarists who descended upon the Iridium to stand on the same stage their master had and to pay tribute to the man who created modern music.

Paul retired from music in 1965, after decades of playing with the greats in Chicago and New York, and on his own television show, recorded in his home. His marriage, to Mary Ford, who also recorded with him, succumbed to the pressure of constant performing and public attention and ended in 1964, though they remained close. Rock ‘n’ roll stormed America, taking the spotlight away from jazz. Burned out, he called an end to his live performances.

Paul retired from music in 1965, after decades of playing with the greats in Chicago and New York, and on his own television show, recorded in his home. His marriage, to Mary Ford, who also recorded with him, succumbed to the pressure of constant performing and public attention and ended in 1964, though they remained close. Rock ‘n’ roll stormed America, taking the spotlight away from jazz. Burned out, he called an end to his live performances.

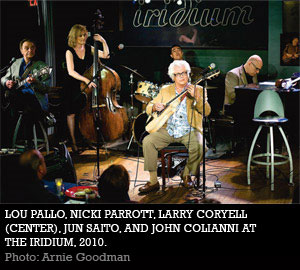

While he had quit playing seriously during his retirement, Paul remained serious about music. He popped up at jazz clubs regularly, listening and learning every chance he got. “He came in 83 times in one year,” said Lou Pallo, who met Paul in 1962 and is currently the guitarist and bandleader of the Les Paul Trio. “Every club that I would go to and work, he would show up.”

A commanding, well-dressed man with carefully combed hair, Pallo played with Paul for 26 years, and it all started when Paul could not stay away from the music, popping up all over and jumping on stage. “He was retired and he stayed local,” Pallo said. “He would just come in, bring his guitar, plug into my amp and play with me all night.” Eventually, Paul’s restlessness convinced him to stop piggybacking on other people’s shows and find a spot of his own, and, naturally, he took Pallo with him.

The two men began heading into New York on a regular basis to check out clubs. They found Fat Tuesday’s—which Paul liked for its small, dark room, with the audience close to the stage—and talked to the manager about playing a spot. The problem was, the young manager had never heard of Paul. After some convincing, the manager brought the owner over, who said, “THE Les Paul?” They wanted a Monday night spot; Pallo worked at another club the other nights, but Fat Tuesday’s was closed on Mondays. Paul said he would work for free, and the owner said, “We are open on Monday nights.”

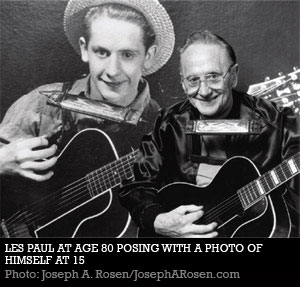

Paul’s career as a musician and inventor began at an early age in Waukesha, WI, playing harmonica and banjo at the age of eight. Around that time he built his own harmonica holder out of a coat hanger and amplified his first guitar using parts he snagged from his mother’s record player. He moved to Chicago in 1934, playing as Rhubarb Red on WLS Radio’s National Barn Dance. He had a great time playing country music, but was drawn by the challenge of Chicago’s vibrant jazz scene. “In Chicago, I discovered I wanted to play both,” Paul said in Chasing Sound! “If I want to make a living, I’m going to do my country music, and if I want to play jazz, well, then I’ll make my $5 a week and play jazz and be with the great ones.”

He soon left for New York, earning a regular spot on Fred Waring’s radio show between 1938 and 1941. He even had his own television show, along with Ford, recorded in his home in New Jersey. The tinkerer who had reared his head as a child continued to look for new ways to create sound. The work he did in his workshop resulted in multitrack recording, mixing boards and one of the earliest solid-body electric guitars, based on an early prototype, called “The Log,” made from a four-by-four piece of wood.

He soon left for New York, earning a regular spot on Fred Waring’s radio show between 1938 and 1941. He even had his own television show, along with Ford, recorded in his home in New Jersey. The tinkerer who had reared his head as a child continued to look for new ways to create sound. The work he did in his workshop resulted in multitrack recording, mixing boards and one of the earliest solid-body electric guitars, based on an early prototype, called “The Log,” made from a four-by-four piece of wood.

Fat Tuesday’s closed in 1995. Shortly before, Ron Sturm had opened the Iridium Room Jazz Club, originally located in the basement of the Iridium restaurant, across from Lincoln Center, in what he called a shoebox-sized room. “The club started very lowbrow,” Sturm, a self-described Jewish Buddhist, said. “Meaning local jazz musicians and chasing people to get them to pay the cover charge. We had a little cash box at the front door, and you had to chase them down for $5. It was an anomaly for the Upper West Side; it was like a place you would find in the Village.” He asked a friend at The New York Times for Paul’s number and called him to ask if he would play Monday nights at the Iridium, without really knowing who he was. “Les Paul is major,” he said. “If I knew how major Les Paul was at that time, I probably would have been too scared to call the guy.”

After standing in the back of the room, arms folded, observing shows for weeks, Paul moved his act there, and from day one, jazz fans, as well as celebrities like Eddie Van Halen, Keith Richards, Paul McCartney, Richie Sambora and Slash packed the room. It was an amazing, and unexpected, comeback for a man who, before returning to Fat Tuesday’s in 1983, had to relearn how to play guitar.

In addition to having quintuple-bypass surgery in 1981, Paul suffered from arthritis so severe he could no longer form many basic chords with his left hand. If he pressed his first and third fingers to the fretboard, the second one would rise. If he pressed his second finger down, the third and fourth would rise. He taught himself to play in a two-finger style, reminiscent of his hero, Django Reinhardt. But even then, the fingers needed coaxing. “I know for a fact that he would put his hands under extremely hot water, extreme hot water, just to get them so he could move them because they were so stiff,” said Tom Doyle, Paul’s engineer for 26 years. “Intermissions he would go put his hands under hot water, get them moving again.”

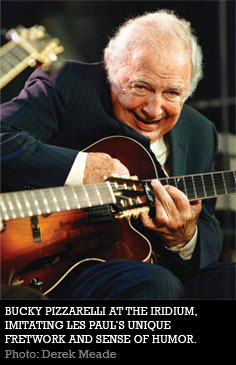

Paul played, and the crowds came. They came to see him in a guitar-lined room with small tables and booths, a bar in the back and a small stage close enough to the crowd for some to reach out and touch him, and for all of them to see the lines on his face, twinkle in his playful eyes and gnarled fingers skillfully wrapped around the neck of his guitar. He signed autographs after the show until everyone was gone, sometimes 100 people a night. At first he signed after both sets, then as his health deteriorated, after the second, with fans from the first set coming back and getting in line, out the back of the small room, up the stairs and out into Times Square. He signed pictures, albums, napkins and, often, Gibson Les Paul guitars, which adoring fans would bring along, often a mistake. “Les was the old style,” said guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli, who played with Paul often. “When he saw a guy come in he would say, ‘Come on up, play, do a number,’ then he would kick you around a little bit.” His playfulness extended beyond musicians and celebrities, to frecklefaced kids hoping to get their guitar signed. He called them up on stage and made them play, and sometimes they played well, and sometimes they did not.

Paul played, and the crowds came. They came to see him in a guitar-lined room with small tables and booths, a bar in the back and a small stage close enough to the crowd for some to reach out and touch him, and for all of them to see the lines on his face, twinkle in his playful eyes and gnarled fingers skillfully wrapped around the neck of his guitar. He signed autographs after the show until everyone was gone, sometimes 100 people a night. At first he signed after both sets, then as his health deteriorated, after the second, with fans from the first set coming back and getting in line, out the back of the small room, up the stairs and out into Times Square. He signed pictures, albums, napkins and, often, Gibson Les Paul guitars, which adoring fans would bring along, often a mistake. “Les was the old style,” said guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli, who played with Paul often. “When he saw a guy come in he would say, ‘Come on up, play, do a number,’ then he would kick you around a little bit.” His playfulness extended beyond musicians and celebrities, to frecklefaced kids hoping to get their guitar signed. He called them up on stage and made them play, and sometimes they played well, and sometimes they did not.

Paul became a Monday night institution in a city notoriously tough on jazz musicians, and on a particularly tough night. “In New York, they have little traditions. A lot of jam sessions used to be on Monday night,” said guitarist Larry Coryell, who, like many others when they met Paul, was immediately summoned out to his house in New Jersey to record. “It was part of the rhythm of New York to go out on Mondays and either listen to, or participate in something. It was more for the musicians, so it was prestigious. New York audiences are very savvy. They are very well educated; there is a nice energy there.”

And as much as Paul came to mean to Monday nights in New York, Monday nights always meant more to him. His dedication to music consumed his life. He had a recording studio in his home and spent countless hours in his workshop, which was filled with his inventions until the day he died; the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Inventors Hall of Fame had asked for several of the items, but he was not done with them yet. Right up to the end he was working on a new hearing aid. “I was up all night last night working on it,” he said in the last interview he gave, to Elmore Magazine. “I have hearing aid companies begging me to put my name on it, but I won’t do it until it is right.” He lived in his workshop, tinkering, not necessarily because he liked to invent, but because his need to create new sounds pushed him to stalk them, corner them and bend them to his will, and when they could not be made with the tools he had, he had to create new ones.

A car accident on an icy bridge in Oklahoma in 1948 shattered his right elbow. Faced with the possibility of never playing guitar again, he told the doctors to set the broken arm close to a 90 degree angle, so he could play. His arm was never the same; he even ate with his left hand. But he played guitar, and he signed autographs until everyone went home. He laughed on stage and told jokes about Viagra, calling himself a condemned building with a new flag pole. He remained dedicated to perfection. When Biréli Lagrène, a Django Reinhardt disciple, played in New York, Paul sat in back and videotaped every show. He videotaped all his own Iridium performances as well and dissected the film the next day. As Doyle, his longtime engineer, drove him to the club every Monday, they discussed the previous week’s show and how to make it better. “I think Monday night is the greatest therapy for me,” Paul said in Chasing Sound! “It gave me a reason to get out of bed. Between going to the bathroom and going Mondays and playing at the Iridium, those are the two greatest things that you can look forward to.”

Paul missed the summer of shows before his death. He had been in the hospital, but the Iridium still planned a big birthday celebration, which he missed. Pizzarelli, one of his favorite guitarists, filled in for six weeks, but plans were still made for Paul to return. “I guess I denied that Les was dying,” Sturm said.

Paul missed the summer of shows before his death. He had been in the hospital, but the Iridium still planned a big birthday celebration, which he missed. Pizzarelli, one of his favorite guitarists, filled in for six weeks, but plans were still made for Paul to return. “I guess I denied that Les was dying,” Sturm said.

And then he died. He passed quietly in the night, and the Iridium continued with his trio on Monday nights in tribute, calling it Les Paul Mondays, and the artists came. Pizzarelli came, and Coryell came, and Steve Miller, Paul’s godson, came, and Jorma Kaukonen, who played guitar for Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna, came, even though he had never played with Paul before. Paul’s legacy preceded him. Jeff Beck came, and he played a two-night birthday tribute, bringing Imelda May to do their best Les Paul and Mary Ford tribute, the same one they did at the Grammys, playing “How High the Moon.” Ricky Byrd, who played guitar for Joan Jett, sat in the audience. “I leaned into Meat Loaf, I tapped him and I said, ‘Dude, I’m crying,’ ” Byrd said. “And he said, ‘I broke down three times already.’ “

They come to pay tribute to the man who made their careers possible. “Any guitarist today, they get sounds out of their guitar that are so out of this world,” Sturm said. “We take it as natural, but where did that sound come from? It came from a guy like Les Paul who took an acoustic guitar that was amplified, but then changed it to be a kaleidoscope of sounds and colors and whatever you want it to be.” Paul played jazz and country, but was the architect of rock ‘n’ roll, heavy metal, soul and any other music created in the modern era. Zakk Wylde, who played guitar for Ozzy Osbourne, played a set with Paul once, and at one point got down on his knees to thank him. Paul told him, “As long as you are down on your knees…”

Few artists can carry a weekly residency. They lack the name, repertoire, skill or some combination. Paul set the standard. His shows were equal parts musical mastery, living history and vaudeville variety show, complete with ribald jokes and banter, having learned to work a crowd from his old friend Bing Crosby. He also set the standard for technical mastery and was the voice of his generation. “People of my father’s generation, when they hear Les’ version of ‘Steel Guitar Rag,’ they throw babies in the air,” Coryell said.

The newly formed Les Paul Foundation, which receives 20 percent of the proceeds from Les Paul Mondays, carries Paul’s legacy, soon to give scholarships to young musicians and engineers, and donations to hospitals and firehouses, just like Paul did with his money from Monday nights. Musicians continue to line up to play his spot. “How long will it last?” Sturm mused. “As long as there are electric guitars. As long as people are playing electric guitars, people will be playing with Les Paul.”

Be the first to comment!