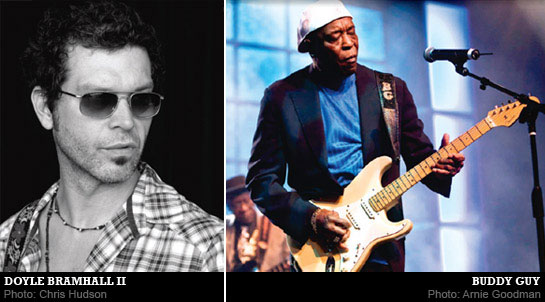

DOYLE BRAMHALL II

DECEMBER 24, 1968, DOYLE BRAMHALL II WAS BORN into a home filled with the blues and rock ‘n’ roll familiar to his birthplace, Austin, Texas. His father, Doyle Bramhall, Sr., was the drummer for blues legend Lightnin’ Hopkins and a regular collaborator with Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Young Bramhall, a lefty, learned to play a right-handed guitar upside down, a unique technique that astounds audiences to this day. By the time somebody told him he was playing it “wrong,” it was too late; this virtuoso was already on his way. At just 16, Bramhall toured as the second guitarist with Jimmie Vaughan’s band, the Fabulous Thunderbirds. Soon after, Bramhall and fellow Texan Charlie Sexton co-founded the Arc Angels, adding members of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s backing band, Double Trouble, to flesh out their lineup. The Arc Angels, though short-lived, found critical and commercial success.

Bramhall made his solo debut with Doyle Bramhall II in 1996, but his career received an enormous boost following the release of Jellycream, in 1999, when he attracted the attention of Roger Waters and Eric Clapton. After Bramhall and wife Susannah Melvoin joined Waters for a summer tour, Clapton, along with fellow blues legend B.B. King, chose two of Bramhall’s songs, “Marry You” and “I Wanna Be,” for their collaboration album, Riding With The King (2000). The album went platinum and won a Grammy, introducing Bramhall’s music to a whole new audience. The following year, Clapton again sought out Bramhall, enlisting him and Melvoin to co-write and perform “Superman Inside” for Reptile, which heavily features Bramhall’s playing throughout. He joined Clapton on his ensuing world tour, becoming his mainstay second guitarist in 2004, a job he held until the Arc Angels reunited.

Meanwhile, Bramhall released Welcome in 2001 with his band Smokestack, and in 2009 reunited with the Arc Angels to release Living In A Dream. Throughout, he has contributed session and touring work to the likes of Sheryl Crow and Derek Trucks. The demand for this lefty’s talents never lets up, recently playing on albums for Susan Tedeschi and Bettye LaVette.

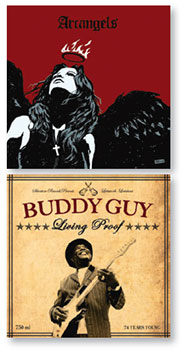

BUDDY GUY

ERIC CLAPTON PROCLAIMED BUDDY GUY “BY FAR without a doubt the best guitar player alive.” Born July 30, 1936 in Lettsworth, Louisiana, George “Buddy” Guy grew up disadvantaged and shy. “You couldn’t watch television or read instruction books, I had to figure it out myself,” he said. “When B.B. King [11 years older than Guy] made a record, ‘I got a sweet little angel, I love the way she spread her wings,’ it took me 29 years to figure out what he meant. Hip hop guys take but three seconds.”

Guy started out on the 1950s Baton Rouge blues scene, where he gulped a combination of antiseptic and wine to ease his stage fright. In 1957, he traveled to Chicago, where Magic Sam helped get Guy signed to Cobra Records, which recorded two singles produced by Willie Dixon. Cobra folded and Guy, Dixon and Otis Rush left for Chess, where Guy recorded his own material with legends like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Little Walter.

Initially joining forces with Junior Wells in the late 1950s, Guy and the acclaimed harpist released Hoodoo Man Blues in 1965 and toured together through much of the ’70s. Their collaboration marked a significant era in Guy’s career, lasting through his move from Chess to Vanguard Records in 1968, and brought about sessions produced by Tom Dowd and Eric Clapton for Atlantic in 1970. Those sessions in turn led to Buddy Guy & Junior Wells Play The Blues (1972) and the noteworthy Drinkin’ TNT ‘n’ Smokin’ Dynamite, a recording of their performance at the 1974 Montreux Jazz Festival.

Guy laid low for years, until he opened his Chicago blues club, Legends, in 1989, providing a world-class venue for himself and like-minded artists. His 1990 performances with Clapton at the Royal Albert Hall boosted his profile beyond the blues world and led to the 1991 release of Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues, a mainstream success. Featuring cameos by Clapton, Jeff Beck and Mark Knopfler, the album went gold, earning a Grammy and five W.C. Handy awards. Much touring and recording followed, including 1994’s Slippin’ In and 1998’s Last Time Around: Live at Legends, recorded with old friend Junior Wells at Guy’s club. Along with his Billboard Century Award and his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, Guy’s recent releases include 2001’s Sweet Tea, 2005’s Bring ‘Em In and 2008’s Skin Deep, again collaborating with Clapton. His recent release, Living Proof, is another Grammy contender (see review, page 24).

What are you listening to right now?

What are you listening to right now?

Doyle Bramhall II: I’ve been listening to classical Persian music. I’ve been playing the oud, which is a Middle Eastern Turkish instrument, for three or four years now. This is part of my journey ’cause I’m just learning. Man, I’m so out of touch with what’s playing on the radio.

Buddy Guy: I listen in my car to spiritual and gospel music on a little station here, and I play it in my car until it fades out. Unless you’ve got a hit record, you hear the same records over and over.

What was the first record you ever bought?

DB: Easy Listening Blues. It was just an instrumental record that B.B. made in ’62 or ’63, with his great lineup, with Sonny Freeman on drums. I asked B.B. about it when I ended up recording with him, and he didn’t even remember recording it because he had made so many records. I was 13, but I didn’t get into buying records until later because my parents have such an extensive record collection of all the stuff I love.

BG: “Boogie Chillen'” by John Lee Hooker, when I was about 16. We didn’t have electric lights, my dad got that old battery radio, and finally we got electric lights, that one light hanging down. Then we got the phonograph, that’s when I got “Boogie Chillin’,” these 78s, you drop them, they break.

Where do you buy your music?

DB: If I’m travelling, I go to mom and pop stores. Here in Los Angeles, where I live, I go to Amoeba, or I do iTunes like everybody else.

BG: I don’t know how to turn on that technology; my children and my manager have to do that. I have my old radio in the car. I liked the kind you have to dial, where you have to pass each station until you said, “This is the one I want to hear.” Now you point your buttons, and your radio dial runs past four or five stations before it stops.

What was the first instrument you played?

DB: By default, drums was my first instrument because my dad played drums and he was a songwriter. We had three drummers in my family and nobody played any other instruments so I switched to bass so we could at least get something else going. When I was 14, I realized the guitar was the way I could actually best get out the tunes that were inside me.

BG: An instrument I tried to make myself, an acoustic guitar with two strings on it—my new CD sings about it. It’s in my club. It was as loud as electric; my parents and my sisters and brothers used to run me out of the house, saying, ‘Somebody can’t play!’ Thank God I was in the South, because this time of year up here it’s too cold to go outside, but you could go outside in Louisiana. I did that a lot. We didn’t have money to buy anything for me to learn on. My parents were sharecroppers; the only time we ate pork and fresh meat was during Christmas. We didn’t have no refrigerator to keep it. We killed a pig, and my daddy would give your daddy a ham you’ll cook, and the next two weeks they killed a pig and did the same thing. After the holidays, no more fresh meat until next Christmas.

What brought you to the instrument you now play?

DB: My dad had right-handed guitars around the house and I just picked ’em up. My dad had inherited Lightnin’ Hopkins’ guitar, because he had played some shows with him, and I started playing that one quite a bit. I used to play Cream and Jimmy Reed and B.B. records, so it’s pretty amazing experience that I would actually work with B.B. and Eric, the first people that I tried to emulate as a kid. My stepfather and my mother exposed me to another side, so I grew up listening to classical music, going to ballets and operas and all that.

BG: A stranger put me in my first six-string guitar. My mother had had a stroke, and I went to Baton Rouge to try to go to my first year of high school. I would sit out on her steps. I had these two strings with this raggedly old guitar. A guy walked by and says, “Son, I see you sitting there all the time, I bet if you had a guitar you’d learn how to play.” I didn’t know who he was. This was probably Tuesday or Wednesday. I was sitting there Saturday, and he came by and said “Are you ready? We’re going to buy you a guitar.” That guy bought a guitar for 52 dollars and some cents, and it was a good one back then. When my sister came home from work, she said, “What is this? A country-ass boy with a guitar.” The guy was sitting there with a quart of beer, and he was drinking and mumbling. I couldn’t play, I was just banging. An’ my sister said let’s put a dollar’s worth of gas in the car and go out to where my mom and dad are, about 60 miles away. They cranked up that Saturday and my dad looks at that guy and says “Ain’t your name Mitchell?” They had grew up as little boys.

I left and came here. My dad knew everybody in Baton Rouge, and last I heard before my dad passed away, 40 years ago, that guy was in Chicago working as a preacher. I went out to find him because I owe him that 52 dollars. I would have loved to pay him back, but I never did find him. He was a gift from God.

Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

DB: Citizen Cope. The stuff that he comes up with is just so unique and original. And his voice—it’s always nice when you just know that person is completely true to themselves.

BG: B.B. King is so modest, I don’t think he would accept it, but he influenced them all. He played guitar without the slide, without any special effects. He made people listen to guitars. He made the price of guitars get out of reach for poor man like I was. I tell him and Eric Clapton that if it weren’t for you, I could have afforded a guitar earlier.

What musician influenced you most?

DB: Stevie Wonder and Paul McCartney, but not the song that they did together. My dad had a huge effect on me because he had all the things that I loved in his voice, and B.B.

BG: B.B. King. We are best friends. I think every guitar player in the world should recognize him, because he raised the price of a guitar from where it was to where it is now. Now you can’t even put a good set of strings on a guitar for 52 dollars. B.B. and T-Bone and all those great guys who taught us were playing for the love of music. They wasn’t getting paid. I’m thinking, “Man, if I learned how to play guitar I’d never have to work, I’d be like B.B. King.” But B.B. said, “Buddy, I didn’t learn to play guitar so I’d be in a decent home and able to pay the bills. It wasn’t like that, with the 99.9% black audience.” When Muddy Waters and B.B. started that thing, black people were playing for blacks. If you saw a white face, you thought it had to be a policeman.

What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

DB: I was 14 when I picked up the guitar, and for the first time I was comfortable—for the first time that I didn’t feel shy or awkward. I started playing four hours or five hours in my room. It really hit when I was 17 and I started to write songs and sing, then that was it at that point. I have a son around 16, and he’s spending hours in his room, he’s finally connecting to something, too. Unfortunately, being a guitar player now is not as lucrative as it used to be, or could be if you made it. From pirating and Google and YouTube, how do musicians make any money now?

BG: It just happened. I was shy. I’ve only been fired once in life. I was about 18, and pumping gas in Baton Rouge, and I made 10 or 12 dollars a week. They found out I could sing and play guitar to one person. The guy said, “Man, I can pay you if you come and sing and play like that.” I could do the Jimmy Reed and one or two Little Walter tunes. He said, “I’ll give you 18 a week.” When I got there I put the microphone between me and the wall, and turned my back to the audience. He said, “Turn around!” I cried, and he fired me. Muddy Waters and them taught me if you learn how to drink a glass of wine, you can get outta that.

The late Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan would say, “I got this from Buddy.” I was just copying B.B.. I was trying to find what B.B. King, Muddy, T-Bone, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Lightnin’ Slim out of Baton Rouge and them was doing, and not finding it, but finding something else. You go looking in the grass for a penny and you might find a nickel.

Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

DB: It would be pointless to have Jimi Hendrix because then I wouldn’t even need to play. Playing a live concert, or in the studio making a record? Making a record, I’d get McCartney on bass. Stevie Wonder on drums and harmonica, and a little clavinet. Steve Winwood on Hammond. I’d play guitar and get Eric as my side guitar player…I’d pay him back with his own coin. Let’s use the people we have there for vocals, and then add Sheryl Crow, David Hidalgo—actually he could be on guitar too. Guesting we could have Ry Cooder. I’m trying to make a guitar orchestra.

BG: The people I learned everything from. Harmonica, I’d have to call Little Walter. Keyboards—B.B. King will answer the same thing—Otis Spann, who died playing with Muddy Waters. They had a drummer named Fred Below, all that Chess stuff. Just give me those three or four pieces. I would like to have Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf on each side of me, teaching me how to sing. If you were interviewing Muddy or Wolf right now, you’d be tapping your feet as they talked. (Laughs) I ain’t that good.

That’s the minimum I would call, but if you let me have everybody I wanted, I would have a band so big, it would take you a week to count them. Albert King, Little Milton, all those guys can’t be beat. I’d say to Muddy or B.B., I’d say, “When you guys play, it’s like I’m in class. I ain’t got no business on stage, I’m supposed to be sitting out there learning.”

What’s your desert island CD?

DB: Almost anything would drive me crazy if I had to listen to it on a desert island for eternity, but it might be Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations.

BG: B.B. King’s Live at the Regal. Not my own record, because I don’t learn nothing from myself. ![]()

[…] Knight matched Bryant with Jeff Beck and Quinn Sullivan, a 16-year-old from Massachusetts, with Buddy Guy. Now that the collective is established, he also tries to group Brotherhood members together when […]