You can’t see them, but they’re everywhere – Three stars behind radio

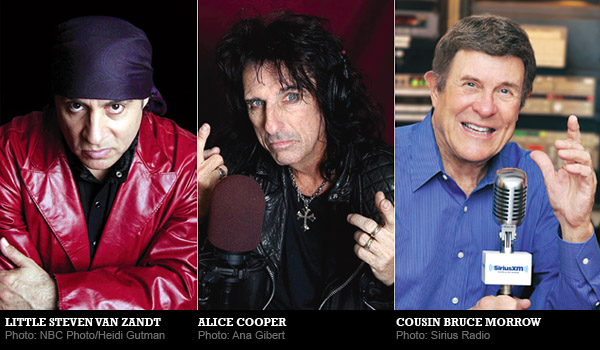

Little Steven Van Zandt

Multitalented Steven Van Zandt is a musician, broadcaster, actor, humanitarian, educator, label owner and businessman. Born on November 22, 1950 as Steven Lento before taking his stepfather’s name, Van Zandt worked with bands and artists in the burgeoning Jersey Shore music scene in the late 1960s and 1970s. Playing with then-local bands such as the Dovells and Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes (which also featured future E Street bandmates Gary Tallent and Max Weinberg), Van Zandt’s most important musical relationship was that with a young singer/songwriter Bruce Springsteen. Springsteen turned to Steven Van Zandt for help in composing and arranging songs on his seminal Born To Run album, after which “Little Steven” became a fixture in Springsteen’s E Street Band.

In 1984, when Springsteen temporarily disbanded E Street to record solo, Van Zandt toured and recorded as Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul. He also became a sought-after producer and songwriter, penning “Baby Please Don’t Go” for Nancy Sinatra and “All Alone On Christmas” for Darlene Love. Van Zandt also founded American Artists United Against Apartheid to protest the injustices in South Africa.

Even though he’s currently on the road with the Boss’ Wrecking Ball tour, Van Zandt is still hard at work on his many projects. He’s become a sought-after actor, starring in HBO’s acclaimed drama The Sopranos and the new Netflix series Lilyhammer. Van Zandt serves as program director for two channels, the Underground Garage and Outlaw Country, on SiriusXM, and programs and hosts Little Steven’s Underground Garage, one of the most popular radio shows on SiriusXM, also broadcast as a syndicated terrestrial radio program in 45 countries.

Alice Cooper

One of America’s most outrageous hard rock artists for over 40 years, Alice Cooper was born Vincent Furnier in 1948, and began performing with high school friends in the ’60s under his given name. When he started a band, the Nazz, he found it bore the same name as a band featuring Todd Rundgren. Furnier changed his band’s name to Alice Cooper and also took that name as his own.

In the ’60s and ’70s, Cooper developed a reputation as a shock artist. His live shows often included costumes and elaborate stunts designed to provoke the audience, including one 1969 bit involving a live chicken, that became one of rock’s greatest urban legends. (For the record, Cooper did not bite the head off of the chicken.) Cooper’s antics and dark persona distressed parents, but kids couldn’t get enough of hits like “I’m Eighteen” and “School’s Out.” Cooper quickly became one of the biggest-selling glam-rock artists in America. His success continued despite the dissolution of his band (Cooper would continue as a solo artist) and his highly-publicized problems with drugs and alcohol. Even in his later career, Cooper courted controversy: the European tour behind his 1987 album, Raise Your Fist and Yell, was almost banned by German officials offended by his stage antics.

Currently, Cooper enjoys success in various forms of media: he has appeared in films and TV shows like That ’70s Show and the upcoming Tim Burton feature Dark Shadows. His radio show, Nights With Alice Cooper, which he has hosted since 2004, is broadcast on over 100 radio stations nationally and has featured interviews with Ozzy Osbourne, Joe Perry, Meat Loaf and many others.

Cousin Bruce Morrow

Bruce morrow, born in Brooklyn on October 13, 1937, has been a seminal voice of American radio for generations. In 1959, he adopted the widely-known handle of Cousin Brucie while working in broadcasting at WINS/New York, and the moniker stuck with him for the rest of his impressive career. After a brief stint on Miami radio, he returned to New York City, where, for the next 13 years, he reigned as a rock ‘n’ roll authority at Top 40 WABC. Cousin Brucie presided over the airwaves at one of most important eras in musical history, broadcasting the British Invasion as Baby Boomers across the country became religiously glued to their radios.

While at WABC, besides hosting the famous Palisades Park (NJ) concert series, Morrow introduced the Beatles at their landmark Shea Stadium concert in August 1965. During this era, he forged a friendship with the King himself during his frequent phone conversations with Elvis Presley. In 1974, Morrow moved to WNBC for a few years, then took a hiatus from broadcasting to pursue other business interests.

In the ’80s, Morrow returned to the airwaves again, periodically filling in on Jack Spector’s Saturday Night Sock Hop on WCBS-FM/New York. When Spector threw in the towel, Morrow took over, renaming the program Saturday Night Dance Party. Out of that WCBS partnership emerged the nationally-syndicated show Cruisin’ America. In 1988, Morrow was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame.

Morrow was broadcasting at WCBS-FM until 2005, when new ownership made the mistake of letting him go. Thankfully, he found his way to SiriusXM, which broadcasts Cousin Brucie’s Yearbook, Cousin Brucie’s Saturday Night Oldies Party and ’60s Pop Hits.

![]()

What are you listening to right now?

Little Steven Van Zandt: The Harder They Come—it’s really, really exciting. The roots of reggae were very much doo wop.

Alice Cooper: Burt Bacharach: Live At the Sydney Opera House, with a full orchestra, and Paul McCartney.

Cousin Bruce Morrow: At home, I usually listen to unusual recordings by artists that I love, terrific material that never gets played on the air. Anyone can play Jerry Lee Lewis singing “Great Balls of Fire,” but how many people play him singing “Me and Bobby McGee”? Car time is my audition time because I’m not distracted by phones and such. I receive about 50 CDs a day from hopefuls who want an opinion.

What was the first record you ever bought?

SVZ: Probably “Tears On My Pillow” by the Imperials. There were five or six singles that I can recall. The first album was Meet the Beatles.

AC: The first record given to me was “Nadine” by Chuck Berry. I was exactly eight years old and my Uncle Vince, a left-handed guitar player, said “You gotta hear this guy!” I just went, “Wow, this stuff is great!” Chuck Berry is still the best rock lyricist of all time. The first record I bought was “All Summer Long” by the Beach Boys when I was 12. Then, 45s were easy to steal.

CBM: A 45 rpm of “The Student Prince” with Mario Lanza. I love Mario Lanza’s voice. My first rock ‘n’ roll experience was Bill Haley & the Comets, then I fell in love with the Everly Brothers, Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis. I still, to this day, love doo wop. I buy a CD and really listen to it; I’m very aware of what’s going on and I keep renewing my ear as much as I can.

What was the first radio station you remember listening to?

What was the first radio station you remember listening to?

SVZ: We would go back and forth between WABC and WMCA. The two AM stations were virtually identical, but they all had their different characters, different DJs. You would just hit buttons back and forth until you heard the song you wanted to hear, but those were both really great stations. We had great radio all along, from the ’50s on, very lucky that way, as opposed to England, for instance, which didn’t have any decent radio until the mid-’60s.

AC: I lived in LA, and I listened to KFWB, a Top 40 station, and we listened to B. Mitchell Reed, the top guy, the funniest guy; he played late ’50s, early ’60s music. Later, in Arizona, I used to listen to KRIZ or KRUX, the two stations that were at each other’s throats in the Top 40, and they were great stations. It was just at the time when the Beatles took over the charts, and when you looked at the Top 40 chart, you’d see where your favorite record was that week. I remember getting one, and the Top 10 records were the Beatles, and I said, “This will never ever happen again.”

Tony Evans was the DJ on the edge, the guy with innuendos that, when you were 12, 13, 14, you kinda got that it was a sexual reference. We were in a band called the Spiders and our record was actually a Number Two record on KRIZ and KRUX, right there with the Beatles and the Beach Boys, so we weren’t just listeners, we were also on the charts.

We were like Ferris Bueller. We never went to class, everybody did our homework for us and we were the coolest guys in the whole school. We were also jocks. Dennis Dunaway, John Speer, the drummer, and myself were four-year lettermen; the three of us were cross country state champions for four years in a row. We had every base covered: we were jocks, in the best band and we had a Number Two record. Come on! We ran that school.

The Beatles were so popular that if you were 15 or 16, you started a band. Everybody did Beatles songs, so we went the other way, and were the only band doing Rolling Stones; then we started doing Yardbirds and the Who, bands with a lot more edge.

I got kicked out maybe seven times senior year because my hair was just over my collar. The principal and vice principal were Mormon elders who didn’t like anybody but the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, and we weren’t going to do any of those songs

CBM: WNEW-AM, with Martin Block’s Make Believe Ballroom. Block was the grandfather of the modern DJ, always playing the Hit Parade or the Top 40 of his day. Little by little, rock ‘n’ roll would seep in, like Fats Domino and then Elvis, taking the place of the Tony Bennetts, the Sinatras and the Doris Days of the time. Martin Block’s reaction was almost violent. He heard a change that was overtaking the “pop era”—which really only lasted ten years or so—and he wasn’t ready for it. Every time the younger generation starts to assert its power, there’s a fight. My parents thought rock ‘n’ roll was the music of the devil when it came out. It’s happening today, with parents not being happy with hip-hop. Some hip-hop lyrics are more violent than early rock ‘n’ roll, but music always reflects the times: early rock reflected the innocence and the prosperity of the ’50s. That’s why we get music that seems a little violent; we live in violent times.

What made you want to go into broadcasting?

What made you want to go into broadcasting?

SVZ: The day I turned the radio on and couldn’t find any of my favorite songs. I realized that the nature of radio was changing because of economic decisions, and it would have to play what was fashionable, as opposed to playing what I thought was the greatest music ever made. It was very clear that there was a format for everything except rock ‘n’ roll. You can hear pop, hip hop, heavy metal, jazz, but you cannot hear new rock ‘n’ roll anywhere, and that’s a tragic occurrence. I decided it’s time for a new format, a station that plays all 60 years of rock ‘n’ roll.

I spent almost a year trying to figure out exactly what I wanted to do. I limited the amount of commercials on the show to eight minutes an hour from what was, at the time, 14 or 15 minutes an hour, which I found unlistenable. My show wasn’t a radical departure from what the typical stations were playing, only I’m playing the early stuff and the album tracks. I made a pilot and sent it to 300 radio stations and everybody turned me down. I said, “Look, if I can sell the show out for a year, take some pressure off, will you then give the okay to the program directors to put the show on?” They said yes. I did that, sold the show out in 15-20 markets and went on the air on 20 stations. The first station that said yes was Q104.3 in New York. I started with the number one station in America.

AC: Dick Clark asked, “If you had a radio show, what would it be?” and I said, “It would be more like early ’60s or late ’60s FM, where there was no word ‘demographics.’” That is the worst word ever, because it has allowed computers to take over the programming. The DJ is the personality, and if he’d go, “I think I want to play ‘Gloria,’” there was no computer that said, “You have to play the Scorpions right now because our demographics say you have to.” I told Dick, “I wanna take it back, let me be the DJ because I would play bands like Love, bands that got forgotten, and I had a relationship with them all. I can play a song by Paul McCartney and I can tell 10 or 20 great stories about me and Paul McCartney. Everybody wants to hear the backline story, a great yarn. You don’t have to embellish the really good stories because they’re so bizarre, which makes for great radio.

CBM: All my life, I wanted to be a doctor. My English teacher in Brooklyn convinced me to take part in a “hygiene play,” which was the way we were taught sex and hygiene at the time. It taught you how to wash under your arms and brush your teeth, and prepared my generation for the world. That’s why my generation is so screwed up. I got the part of a cavity, dressed up as a cavitied tooth. On the stage that day, something happened: I loved the feeling of getting in touch with an audience, and I haven’t stopped talking since. I started auditioning for the All-City Radio Workshop in Brooklyn. My love for radio really developed there.

What bands influenced your taste the most?

SVZ: My big bang as both a DJ and a performer is the British invasion years, basically ’64-’68; those are the years where everything that mattered happened as far as I’m concerned. I believe that the British invasion and soul music of the time remains the greatest music ever made. Also, it was the only time in history when the best music being made was also the most commercial.

AC: One of my loves is doo wop music. I love the Skyliners and the Crests. It’s the only thing my wife and I don’t agree on. She was born in 1956. These guys were singing their hearts out to a girl, and they were all greasers. Dion and the Belmonts were juvenile delinquents, stealing hubcaps when they weren’t Dion and Belmonts.

I used to watch American Bandstand every day. Music was really important to me. My dad loved Sinatra, so I really liked big bands, but I really loved the whole ’50s and ’60s music. Chuck Berry, Little Richard, they really rocked, but also Neil Sedaka and the Orlons. I couldn’t wait to hear the Top 40 to hear what the new record was going to be.

Then the Beatles came along and you just went, “What was that?” The Beatles were a huge influence on me, and the Rolling Stones—the British invasion basically. We would watch Hullabaloo and Shindig! and go, “Did you see that band with all the hair?” Every week there was a new band.

The British invasion had a big influence, but we were the first generation to be brought up on TV. We’d be doing a hard rock song and go into The Man From U.N.C.L.E theme, and one guitar could play the I Spy theme, then the James Bond theme over it and then go back into the song. We used to end our show with this gigantic psychedelic rave-up song based on the Patty Duke theme, and the audience’d go, “Was that a hallucination?” We looked like Clockwork Orange and one of the guitars was playing the Petticoat Junction theme.

CBM: I love the sound of the Platters and other doo-wop groups. I love rockabilly; I think it’s the purest foundation of rock ‘n’ roll, the prime root. Guys like Carl Perkins, Buddy Holly. I always loved Johnny Cash. I love Little Richard. Elvis, of course, was it; Elvis sealed the deal. Growing up as a kid in Brooklyn, this new sound didn’t belong to my parents; I knew it was mine; it was written for me. I listened to it, danced to it and it gave me a solace that this was for me. My little radio became my friend.

If you were a station director, what DJs would you like on your station?

SVZ: I’ve actually had that opportunity because I have two stations on Sirius where I hired 15 DJs. I’m proudest most of picking Andrew Loog Oldham, who was the manager of the Rolling Stones and who was not a DJ. I wanted some DJs I grew up with—the Cousin Brucies. Alan Freed, Murray the K, Dewey Phillips come to mind, some of those crazy guys who were just so wild, so influential, like Wolfman Jack—you couldn’t be too over the top for me. Those were all great, great personalities. I think my fondest memories are mostly the guys with the more energetic, AM radio styles.

AC: I would find guys that truly loved music and were not interested in anything but the music, guys like Dr. Demento and Little Steven and people that really, really know their music. I’d make them DJs and tell them, “Play whatever you want to play.” If it’s Sinatra, play Sinatra, and if you wanna play the Stooges right next to that, play the Stooges. If you wanna play an hour of the Beatles, do it. I would say, “It’s your four hours.” It makes the DJ the artist.

CBM: I’m a Brooklyn kid and I founded the radio station at NYU. I spent almost my entire college career building this radio station and that was the best education I could get. My first job was actually at Mutual Broadcasting. Mutual is now WOR family, and I was a producer and I worked with on-air talent, getting their commercials ready and giving them what they have to do next and making sure the music is set up or in those days, talk, getting the guests lined up. Producing is a good experience, and gives you a bird’s eye view of what’s going on.

Alan Freed sounded like a person talking to me and he always sounded like the music. He had the rhythm and beat with the music he was playing. He used to take a NY or Bronx telephone book and beat on it in rhythm to the music. I’d never heard anything like that and I guess he helped develop what I did. I always teach anybody who works for me that all these shows have to have a rhythm.

What’s the one record you never get tired of hearing?

SVZ: Oh God, there’s a lot…12 X 5 by the Rolling Stones is probably my favorite album of all time—an American album, it didn’t exist in England actually. 12 X 5 and December’s Children are two of the best, along with their first and Out of Our Heads.

AC: I don’t think you could ever get tired of Sgt. Pepper, or Pet Sounds, or Laura Nyro’s Eli and the Thirteenth Confession. Forever Changes by Love never ever gets old, or Traffic’s first album, Mr. Fantasy; I would listen to Days of Future Passed by the Moody Blues all the time, although it’s certainly not the kind of music I’m going to play.

Every once in awhile, I’ll play a song that does get played a lot, but for about 90% of it, I’m saturated. I have a thing I call “the expiration date is almost up.” I give a song another eight plays before I put it in the freezer.

CBM: First off, I’d better get food delivered to this desert island or I’m not going! I’d want Pavarotti—I’ll always love his voice. I’d want to have a library of rock ‘n’ roll at its peak, in its development stages, including the following: pristine copies of the Everly Brothers, the Platters, several Elvis albums—not the movie albums, which I think are inane and ridiculous (and so did he)—but early Elvis, when he was one of the greatest entertainers of all time. Beatles albums, a few butt-kicking Rolling Stones albums—I’d absolutely have to have “Not Fade Away.” Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Johnny Cash and every Buddy Holly record. I’d like the Kinks, Gerry & the Pacemakers, Van Morrison. I’d need some more time to think about what I’d need to complete my list.

Where would you like to see radio go?

SVZ: In my discussions with my own affiliates, which are the biggest classic rock stations in the country, I’ve always been trying to persuade them to play a bit more new stuff, which they just tend not to do. I’m not going to tell them how to run their business—they obviously are successful at what they do—but I try to persuade them to play new rock ‘n’ roll, and the new stuff reminds people that this is very much an art form that’s alive and well, maybe not as well as it used to be, but ongoing, kicking and still producing new music. We’re about to celebrate our 10th anniversary and we’ve introduced 500 new bands, great new bands that people need to support somehow and help these people make a living or they’ll never get replaced, and they need to get replaced.

Pretty soon, the bulk of what I play is not going to exist anywhere else. My playlist is about 4,000 songs, from Little Walter to Elmore James to the Ramones to the Clash, virtually none of which can be heard anywhere else. Where radio’s going, you’re just not going to hear these songs anywhere, be they old or be they new; you’re not going to hear any of the ’50s, ’60s, half of the ’70s, and you’re not going to hear anything new, and that’s a lot to be missing. So maybe someday somebody will take a chance on my thing.

AC: I would like to see it less corporate. The worst thing in the world is a bunch of guys in suits who don’t even like the music programming. Let people who know music program the station. I know you have to sell ads. But you could just feed the audience pabulum or feed them meat and potatoes. I think we’ve babied this audience enough; challenge them a little bit! Listeners go, “Wow, I didn’t know I liked that until I heard it just now.”

At WABC, the programming got so bad that the producer put up three lights in the studio for the DJ. When the red light went on, that meant it was time to play the Number One record; the blue light, time to play Number Two, and when the yellow light went on, play the Number Three record. You’d play those records every hour or so; the Number One record played every 45 minutes.

I’m just trying my hardest to make radio fun again. The guys that worry about selling the product, every single one of them have tried to get me to change my show and then they look at the ratings and it’s Number One and they go, “Tell Alice to do whatever he’s doing,” because ratings speak very loudly to them.

CBM: I honestly believe that there is room on the spectrum for all forms of media. Mass media will have a market as long as the suits who control things know their market. The problem with terrestrial radio is that they’re unsure of where they want to go with it and who they want to appeal to. Terrestrial radio can’t get their old audience back; they need to get a new audience. They have to re-identify their audience. Satellite had to do that because it was brand new; there was no pre-existing audience. Audiences today are reasonably fickle; they like to taste all forms of media. They don’t just stick to one thing. I’d try to give people as wide a selection of music as I can. On my show, you can hear an Al Jolson song from 1928 followed by a cover of the song from 1968.

People liked listening to the Dan Ingrams and the Ron Lundys because they could relate to them, they were tangible personalities that people could connect to. We were like friends to people. That got lost, though. Everything got so impersonal on radio, and that has to change. Gaga has a very good voice, but she’s a marketing person, she’s surrounded by marketing people and money makes the world go round. That’s what people love about my kind of broadcasting, they feel like they’re listening to their friend. That’s what radio lost over the years. It lost a friend.

Be the first to comment!