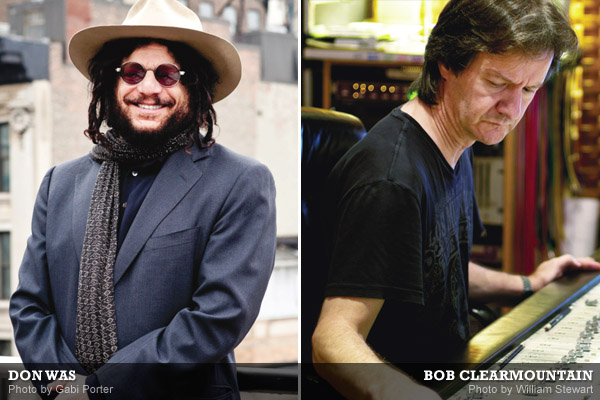

DON WAS

Born on September 13, 1952, in Detroit, Michigan, Donald “Don Was” Fagenson grew up listening to John Coltrane, Miles Davis, the Rolling Stones and various artists from the Detroit music scene. Was started out as a session bassist before forming eclectic rock group Was (Not Was) with friend David Weiss. The group released four albums and found some success, but in 1979, Was started producing, which would make him a legend. The list of artists he would go on to produce is perhaps without equal: the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, John Mayer, Bonnie Raitt, Ringo Starr, Iggy Pop, Bob Seger, Al Green, Lyle Lovett, Kris Kristofferson, Joe Cocker, Willie Nelson, Elton John, Randy Newman and many more.

In 1989, Was’ work on Bonnie Raitt’s Nick of Time—which sold five million copies, won four Grammy awards and revitalized Raitt’s career—solidified his status as a top-tier producer. Gigs producing Ringo Starr, Willie Nelson and Roy Orbison quickly followed and Was never looked back. In addition to his production work, Was has also branched out into films, serving as a musical director and consultant for films like Thelma and Louise, The Flintstones and Days of Thunder. He directed Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times, a documentary about the former Beach Boy that won the San Francisco Film Festival’s Golden Gate Award. Was also won a Grammy for Producer of the Year in 1995, when he worked with Wilson, the Highwaymen, Raitt, the Stones and Dylan.

In 1989, Was’ work on Bonnie Raitt’s Nick of Time—which sold five million copies, won four Grammy awards and revitalized Raitt’s career—solidified his status as a top-tier producer. Gigs producing Ringo Starr, Willie Nelson and Roy Orbison quickly followed and Was never looked back. In addition to his production work, Was has also branched out into films, serving as a musical director and consultant for films like Thelma and Louise, The Flintstones and Days of Thunder. He directed Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times, a documentary about the former Beach Boy that won the San Francisco Film Festival’s Golden Gate Award. Was also won a Grammy for Producer of the Year in 1995, when he worked with Wilson, the Highwaymen, Raitt, the Stones and Dylan.

From 2009 to 2012, Was hosted the weekly Motor City Hayride radio show on Sirius XM. In 2010, Was remastered the acclaimed reissue of the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main St., followed by the Some Girls reissue the next year. In 2012 alone, Was became president of legendary jazz label Blue Note Records, played bass and produced the Love for Levon [Helm] fundraiser, played the Americana Music Association Awards show, recorded two new tracks for the upcoming 50th anniversary Stones’ album, produced Kris Kristofferson, Carlene Carter, John Mayer, and co-produced Aaron Neville with Keith Richards. This here is one busy guy.

BOB CLEARMOUNTAIN

Born January 15, 1953 in Connecticut, versatile Bob Clearmountain (born Chiaramonte) took to electronics and music at a young age. After playing bass in several local bands as a teen, Clearmountain was introduced to the world of recording when his band cut a demo at New York’s Media Sound studio. After the band split, he returned to the studio in search of a job. Starting as a delivery boy, Clearmountain was promoted within hours on his first day and immediately began working as an assistant engineer on a Duke Ellington session.

In 1977, Clearmountain became the chief recording engineer at Power Station Studios (now Avatar Studios). With early work for bands like Chic and Sister Sledge, Clearmountain’s reputation grew quickly throughout the ’80s, and he began mixing records for the Rolling Stones, David Bowie and Roxy Music. 1984 proved to be a watershed year in Clearmountain’s career, when he co-produced Bryan Adams’ Reckless, Hall & Oates’ Big Bam Boom and mixed Bruce Springsteen’s classic Born in the U.S.A. Clearmountain continued to work with top artists like Pretenders, Simple Minds, INXS, Huey Lewis, Willy DeVille and Tears for Fears for the rest of the decade and into the next.

In 1994, Clearmountain built a studio in his Los Angeles home and began working independently. Having racked up four Grammy nominations, an Emmy win and 10 Mix magazine TEC awards (seven for Best Recording Engineer, two for Best Broadcast Engineer and the Les Paul Award, for those who set the highest standards of excellence in audio technology), Clearmountain continues to work with the best in the business. In addition to Bruce Springsteen, he is currently working with John Fogerty. Clearmountain and his wife, Betty Bennett, also currently host radio shows for local Santa Monica radio station KCRW at their Berkeley St. Studio.

In 1994, Clearmountain built a studio in his Los Angeles home and began working independently. Having racked up four Grammy nominations, an Emmy win and 10 Mix magazine TEC awards (seven for Best Recording Engineer, two for Best Broadcast Engineer and the Les Paul Award, for those who set the highest standards of excellence in audio technology), Clearmountain continues to work with the best in the business. In addition to Bruce Springsteen, he is currently working with John Fogerty. Clearmountain and his wife, Betty Bennett, also currently host radio shows for local Santa Monica radio station KCRW at their Berkeley St. Studio.

![]()

What are you listening to right now?

Don Was: It goes through cycles. Might be lunar cycles. To tell you the truth, lately, just to clear my head, I’ve been listening to the Heart & Soul channel [Sirius/XM]. Nothing too taxing, but great music.

Bob Clearmountain: I’ve been listening to Springsteen ’cause I’m mixing a Springsteen show at the moment. It’s really embarrassing for me that I spend 10-12 hours a day, every day, in the studio mixing so I don’t get much of a chance to listen to anything. The last thing I feel like doing after mixing all day is putting on a record. I listen to NPR most of the time.

What was the first record you ever bought?

DW: The Four Seasons: “Candy Girl,” backed with “Marlena,” in the fourth or fifth grade—pre-Beatles.

BC: Meet The Beatles! and Introducing… The Beatles, the first two albums that came out here. I was 12 or 13.

Where do you buy your music?

DW: I wish it was mom and pop stores. They’re hard to find. I love record stores, and I support them when I can, but much of what I do is at 2 o’clock in the morning. I’m a big iTunes guy—it still blows my mind that you can get any song you want instantly. You’re talking to a guy who grew up on transistor radios, little things with one-inch speakers that would really make a laptop speaker sound hi-fi . I grew to love that sound. I don’t want to hear a ball game in high-def, I want it to sound like I’m barbequing in the backyard. I like that compressed sound. “Like a Rolling Stone,” on AM radio, the crack and snare drum and how the organ part comes in—that’s a riveting thing, better in low-fi. It’s an emotional response based on my own lifetime experience.

BC: I download it. I hate to admit it, but I listen to Pandora and radio most of the time. Right now I have an Internet station called Radio Paradise which is a really eclectic mix of music.

What was the first instrument you played?

DW: Piano. I started taking piano lessons when I was eight.

BC: The ukulele, when I was ten or eleven.

What brought you to the instrument you now play?

DW: That’s easy. I was the second best piano player in my high school, and there were no bass players. When I was 12, I saw McCartney playing a guitar that had four strings, so I thought the bass was a guitar with four strings.

I auditioned for a band, and my audition piece was “Walk Don’t Run,” and I just played the lower four strings. They were older guys, and the guy said, “Oh that’s good you know the chords, now let’s play the bass part.” So I said, “I just did.” I was really embarrassed. Then the guy explained what the bass was.

BC: The Beatles came out and there was something about the bass that I liked. Bass seemed simple because it only had four strings. I’m still a bit of a bass player. I liked shows like Shindig! where the bass player would be somewhere on the side. The bass player wasn’t the guy in front except for McCartney. I never wanted to be the guy up front, I wanted to be the guy that contributed to what was going on, but behind the scenes, which is why I ended up doing what I do. I liked playing music but I didn’t like being up there with people looking at me.

Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

DW: You’ve written some very quirky songs. Thank you. That is a compliment. I’ve been really fortunate to be able to write quirky songs with David Was, something that has its own voice that’s not like anything else. I grew up when, if you handed in your record and someone said, “Wow, that’s cool; it reminds me of (blank),” Fuck you! Those were fighting words, an insult, and I still hold to that. The goal is to try to do something different, and there’s nobody like David Was.

John Hiatt can write a song. You play Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” and unlike anyone else on earth, he’s got 600 other songs as good as that one. People approach songs with their own set of neuroses, their own issues and Bob writes songs that are specific, but broad enough that everyone can project their own unique inner life on those songs and infuse them with meaning. The art of that is knowing just how much information to give in order to evoke something without being so specific that you prevent people from making it their own.

BC: I wish I could write. I have so much respect for writers, people like Springsteen. Have you ever tried? Yeah, but you wouldn’t want to hear. If somebody you could teach you how to write, who would that be? Well it would be more like Springsteen, Neil Finn or Chris Difford and Glenn Tilbrook—I’m a big Squeeze fan.

What musician influenced you most?

DW: You wouldn’t necessarily hear it in my playing, but as far as setting a goal: Miles Davis, who retained a unique voice throughout his career. You can pick him out in an instant on a record from the ’40s and from something he might have cut right before his death.

BC: Growing up, I was into British rock: the Beatles, Stones, the Who, Traffic. The Beatles, especially. I was a big Leon Russell fan. I would have to throw the Police in there. I’m a huge Crowded House fan. I had tickets to a show and two days before they were playing, their tour manager called me and said, “They’d really like you to come to the show.” I told him I’d be there anyway, and he said, “Would you be interested in mixing our next album?” I said, “Are you kidding?,” and ended up mixing three or four of their albums.

What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

DW: It might cheapen it to give you the stock answer, but it’s really true: seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. I know a whole lot of musicians my age, from more than any other year, and that’s because we were all 12 years old when the Beatles were on Ed Sullivan and you saw the girls screaming, and the music was riveting. If we were a little older and wiser, we wouldn’t have been dumb enough to say, I want to do that, and actually stick to it. It was an idiotic move to not back it up with another skill set.

The real answer to that question is that there’s no one specific thing; it’s those moments, like addictive drugs. You have a moment and you start chasin’ it again. I still have those moments.

BC: I was a late child. My parents had already put my brother through school and they said, “We’re retiring; we can’t afford to put you through school. You can go to the University of Connecticut, or you’re on your own.” I was really into music, and my girlfriend’s dad ran this company that made electronic parts, and he had dB Magazine, a recording magazine back then. There were pictures of tape machines and big consoles with a thousand knobs on them, and I said, Wow how cool is that!

I built this little recording studio in my basement. I was recording my band and my friend’s band, and all of a sudden a bell went off and I went, Ah, I know what I want to do. I didn’t like being on stage. I didn’t think I was ever gonna be a good enough musician, and that was that. I was about 17.

Then at 19, the last band I was in was doing a demo, and the band split up because the lead guitar player was sleeping with the lead singer’s girlfriend. I went, OK, that’s it! I’m not depending on these idiots anymore. I’ll just record them.

Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

DW: Funny you should ask. When I was in high school, I remember walking home asking myself this question. The personnel would change except I was playing bass, Merle Haggard was singing. Miles was playing trumpet and Wayne Kramer was playing guitar. I always wanted to put that band together.

On our first Was (Not Was) record, we had Marcus Belgrave, who played trumpet with Charles Mingus and Ray Charles. He wove these lines opposite Wayne Kramer’s guitar over this dance groove. It was not that far off from what I was hoping for in high school. I made an orchestral Was album and Merle Haggard did sing on it; with Terence Blanchard (trumpet) and Herbie Hancock played piano, so that came close. On another orchestral Was album, with 13 people playing, Robbie Turner played pedal steel and some mandolin. I think pedal steel guitar is the hardest thing in the world to play. Herbie was playing these very deep voicings and this cat was able to float them, to match Herbie, and blew his mind. Everybody’s mind. Still, I’ll put Greg Leisz in there on pedal steel. David Was? Of course—he’s playing flute. Didn’t I tell you? [laughs]

BC: The guitar player would be Hendrix for sure. The singer would be either Bowie or Mick Jagger, hard to say. Keyboards… Steve Winwood, although he’s a great singer as well. Leon Russell on piano for sure. I should really think about it, ’cause I’ll hang up and say, Oh no I should have said… McCartney would be the bass player with John Lennon on vocals and rhythm guitar. I’m just such a Beatles fan. Matt Chamberlain on drums and the horn players from Al Green’s records. If you had this band and were going to record them, who would you have with you in the studio? I would engineer and mix it. As far as producing, Don Was. Definitely Don Was, for sure. Brilliant.

What’s your desert island CD?

DW: Speak No Evil, by Wayne Shorter.

BC: So many will disagree with me on this I’m sure, which is good I think. There’s a Todd Rundgren record from the ’70s called A Wizard, A True Star, a crazy sounding record. If I had to do a lot of work around the house or cleaning, I’d put that on; it just gets me going. I’ve listened to it probably hundreds and hundreds of times. Or The White Album

Be the first to comment!