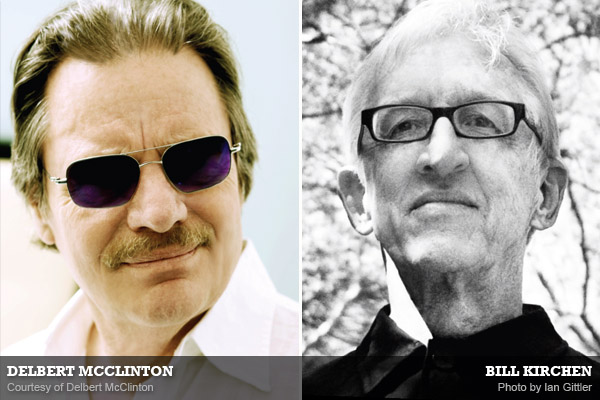

Delbert McClinton

Born in Lubbock, TX, on November 4, 1940, Delbert McClinton’s earliest memories include seeing Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys at the Cotton Club in Lubbock with his parents. By the time he hit his teens, McClinton had relocated to Fort Worth, TX, and was already hitting the local stages. McClinton’s group soon became the backing band at Fort Worth’s legendary Skyliner Ballroom, where the young artist received firsthand wisdom from blues masters like Jimmy Reed and Howlin’ Wolf.

After releasing several local and regional singles, McClinton cracked the charts in 1962 with his harmonica work on Bruce Channel’s “Hey! Baby.” During a subsequent tour of England, McClinton gave some harp lessons to John Lennon, who later put the schooling to use on some of the Beatles’ hit singles. By the early 1970s, McClinton had moved to Los Angeles to record with his old friend Glen Clark. The duo, under the name Delbert & Glen, released two albums with Atlantic Records. McClinton then returned to Texas, signed with ABC Records, and in 1975, released his solo debut, Victim of Life’s Circumstances. Throughout the rest of the decade, McClinton released a string of successful albums and songs, including 1980’s Top 40 hit “Givin’ It Up For Your Love.”

McClinton scored his fi rst Grammy nomination in 1989 for Live from Austin and his first win in 1991 for his duet with Bonnie Raitt on “Good Man, Good Woman.” The following year, McClinton collaborated with Tom Petty, Melissa Etheridge and Tanya Tucker, with whom he partnered on the popular “Tell Me About It.”

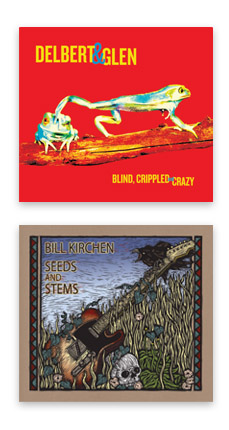

After a series of commercial peaks and valleys in the ’90s, McClinton scored two more Grammys and topped the Billboard blues chart with a series of albums in the 2000s, including Nothing Personal, Cost of Living and Acquired Taste. He teamed up with Clark again for his most recent release, Blind, Crippled and Crazy.

Next January marks the 20th anniversary of his popular Delbert McClinton & Friends Sandy Beaches Cruise, a week-long trip featuring performances by artists such as Marcia Ball, Richard Thompson, Paul Thorn, Band of Heathens and the McCrary Sisters, among others.

Bill Kirchen

Born in Bridgeport, CT, on June 29, 1948, Bill Kirchen was raised in Ann Arbor, MI, where the blues-saturated Midwest informed his musical path. Kirchen started out on the classical trombone, but the combination of a growing folk movement and the influence of his guitar-playing cabin counselor at Interlochen Center for the Arts attracted young Kirchen to the roots of American music. Soon, Kirchen was repairing his mother’s dilapidated banjo and hitchhiking his way to the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, where “the top of his head flipped opened, and it would never shut.” Folk music couldn’t contain him, however; after witnessing Bob Dylan go electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, he knew he would follow suit. The “Titan of the Telecaster” was born.

In 1967, Kirchen co-founded Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, which blended country, rock ‘n’ roll and honky-tonk into one of the more happening sounds in a San Francisco scene jammed with happening sounds. Commander Cody’s unique mix became the seeds of Americana music, and the genre’s growth would be the result of tender nurturing from Kirchen’s Telecaster. Kirchen would remain with Cody for the span of seven albums, including the classic Live from Deep in the Heart of Texas. Located on that magnum opus is Kirchen’s rebellious “Too Much Fun,” which he brought back and ramped up as the opener on his newest release.

In 1976, Kirchen left California and the band to form the Moonlighters, with whom he recorded two albums. In 1986, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he formed the Too Much Fun trio. The band found acclaim and success during the ’90s neo-traditional country boom.

In 2001, Kirchen received a Grammy nomination for his instrumental “Poultry in Motion.” The next year, he was inducted into the Washington Area Music Association Hall of Fame, impressively sandwiched between John Philip Sousa and Dave Grohl. Widely considered the founder of the “twangcore” movement—part country, part rockabilly, part boogiewoogie—Kirchen’s musical influence remains strong, heard in music from Dave Alvin to Wilco. Kirchen’s newest album, Seeds and Stems, finds that trademark sound in fine form, including an extended version of “Hot Rod Lincoln” teeming with 40 or 50 classic guitar riffs.

![]()

What are you listening to right now?

Delbert McClinton: I really spend a lot of time with jazz from the mid-’40s through the ’60s, like Miles Davis, Coltrane. My mother’s youngest sister was a teenager when I was seven or eight, and she had all of the Charles Brown stuff, Nat King Cole and all of that. I love all of that. I just kinda sponged it up.

Bill Kirchen: I’m not listening to a whole bunch of recorded music right now. We play so much, I need to kinda rest my ears in between. We travel in the van a lot, and somebody wants to not be hearing music—maybe they want to go to sleep, or their ears are tired. I just heard Ray Wylie Hubbard recently, and Paul Thorn. I still listen to old stuff—’60s soul sometimes.

What was the first record you ever bought?

DM: “Black Slacks,” a song from the early ’50s. Terrible song at the time. Bbbbbb, black slacks. Duh duh duh duh. Bbbbbb, black slacks. It just was early rock ‘n’ roll, and I liked it. I was 12 or 13.

BK: “Bristol Stomp” by the Dovells and “Big Bad John” by Jimmy Dean. Of course, that was a narrative country song. I still love to hear that (he sings: “Big Bad John”). I’m too lazy for records. They sound better; I know they do, but I don’t mind MP3 players or CDs.

What was the first instrument you played?

DM: Harmonica, but that was before I started playing blues harmonica. I was 14 and was playing stuff like little Irish ditties (sings). I learned to play “Moon River.”

BK: Trombone. I was a classical music guy. I was tall and had long arms, so they gave me a trombone. And the lowest note on a trombone corresponds to the low E string on a guitar. I kind of made my mark, such as it is, hanging around that lower quadrant, bottom strings—nobody made it above the seventh fret. I often think that my ear might have gotten trained, and I liked the low sound.

What brought you to the instrument you now play?

DM: I played guitar. I played a little bit of piano. In about 1952, my brother brought home a friend that had a guitar… and that set it all a-rolling. I had to do it, you know. I was about 16, and my brother, who’s older, and myself—we found a guitar for $3.50. It was a very, very used old Kay F-Hole, and a Kay was a cheap guitar. The neck was warped and the strings were nearly a half inch off the fret board. I spent two or three years trying to tune it. You couldn’t tune it. But I played that thing till my fingers bled. One of the first bands I’d been with had two singers—me and another guy—and I just fooled around with the piano, and then one day, I ended up playing the piano while he stood up to sing.

I write on both the guitar and piano, the difference being that on the piano, it’s easier to pick out chords. Every day, I get up and have a cup of coffee and either pick up a guitar or sit down at the piano and see what comes out. Sometimes something does and sometimes nothing, but you gotta expose yourself to it.

BK: I was at Interlochen Arts Camp in Michigan, a well-respected classical music place, studying trombone for the Michigan All-State, and my cabin counselor played guitar and sang folk songs, right around when commercial folk music like the Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul and Mary were just getting popular. I found a banjo in my mom’s attic, and a guy put a new head on my banjo, and I got the How to Play the 5-String Banjo book and record by Pete Seeger, and I was off and running. I hitchhiked to the Newport Folk Festival in 1964 with my tiny little five-string banjo and the little case that my mom had made for me out of naugahyde, and I was the happiest guy in the whole fuckin’ world. I was just mad for it. In ’64 and ’65, I hitchhiked from Ann Arbor. The album cover of The Blues at the Newport 1964 was shot from behind Mississippi John Hurt, and there’s me in the corner with a big grin on my face. I just turned 16 like a month before, and I wanted to be Mississippi John Hurt, and that’s when I started to learn to play guitar.

Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

DM: I wish I could give you a long list, but… I admire jazz a great deal, but that’s way too educated for me. I don’t read music, and I don’t write music; I make music up. If you can’t speak the language of written music, you’re a bit handicapped. I don’t, but I can hum it or point it out and show you where to pick it and stop it. It’s something that’s always been with me.

There’s a song going on in my head all the time, always a riff or a tag of some kind. I used to walk around keeping time, playing drums with my teeth, but I finally quit doing that because I wore them down. I write blues, but I try to always lead with the possibility of a way out… like, It’s bad, but it will be all right.

BK: I’d love to write one with my friend Nick Lowe, but I’d be really intimidated. I’d love to write one with Elvis too; that’d be great.

Costello?

Yeah, not the dead guy. I love the whole folk canon. I noticed I like morbid themes. I like really sad songs.

What musician influenced you most?

DM: Charles Brown was a big influence, an absolute genius, and of course Ray Charles, but I grew up in West Texas listening to Bob Wills and Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell and Ernest Tubb, and all of the music going on then—country and popular music, I guess is what you would call it.

BK: Thinking, thinking, thinking…I can’t get past Doc Watson. That’s what my brain’s telling me, and I’m surprised. The whole thing was so sublime—his singing and playing and his choice of songs—and I also think the reason that I could play “Hot Rod Lincoln” was because I’d been practicing Doc Watson fiddle songs.

In terms of writing, I was probably influenced by listening to musicals and the Harry Smith catalogue more than, say, the Beatles, but I would have learned it, of course, first with the New Lost City Ramblers and Pete Seeger. I still think those are great songs, just some really deep, really primal stuff.

What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

DM: Back in the early ’60s, this girl I went to school with, she was married and lived across the street, and I remember one day, she was asking me, “When are you going to get a job? Are you still going to be doing this when you’re 30?” and my first thought was, “God, I hope so!” All of a sudden, it was obvious that I was not going to do anything else. I had all kinds of jobs, but I just couldn’t do that. I got fired from every job I ever had, jobs a smart monkey could do.

It’s been the passion that’s kept me alive and still does—that I still love doing this so much. I can’t get this feeling from anything else.

BK: When I started to learn to play guitar, I started to finger pick “Candy Man,” and “Rich Woman Blues.” And that picture on the record cover—that’s what ruined me for normal work.

It’s funny, because on the one hand, in the hubris of youth, I just sort of assumed that I could, but on the other hand, like many performers, up on stage with [Commander] Cody playing for 250,000 people at the last Led Zeppelin show, and part of you says, “I’m a fraud. I’m bullshit.”

I’ve never had a game plan. I was on stage in 1965 with my jug band, the Who Knows Pickers, and also on the bill were the Iguanas with the young James Osterberg (Iggy Pop), singing “Jolly Green Giant.” Maybe it happened when I first went to California in about ’69, and there I am at the Family Dog on the Great Highway with the Commander Cody band, opening for the Dead.

When did you stop carrying your own bag, driving your own car?

DM: Oh, I still carry my own bags, but the first time I didn’t, I liked it. It’s a big help to have a crew, but most of my life, it was me and the band who set all our gear up and tore it down and loaded it out, and it was fine. What the hell? That’s my stuff. In the mid-’80s, I had a crew—a couple of guys that did all that for us. That’s what I have today; two guys that do all that for us. We traveled with everything in one bus—all our equipment and all of us; it was like going to space with a bunch of people every time we hit the road.

I never made any money in this business until I was 53 years old. Every record company that I’ve been with since 1971 has gone out of business while I was on the road. But I’m sitting on top of the world. I am. I couldn’t be a more fortunate guy.

BK: I’ve never not carried my own bags! I didn’t have to carry my own amp; that kinda happened early for me.

I remember we got our first band bus, probably in about ’70. Rock ‘n’ roll bands traveled in either planes or rent-a-cars, so we were emulating the country guys that had the busses with bunks. We bought a ’54 Greyhound, super scenic cruiser; we spent about 15 grand. [Commander Cody] George Frayne’s brother, Chris Frayne, painted it in glorious rope lettering, smoke signals from a train, and we put in 12 bunks and an upper and lower lounge and a cassette player, cards downstairs, what-all upstairs. When we were in that bus and hit the road, I was like, “How could anything possibly get better than this?” Man, I had way more fun than I deserved.

Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

DM: I’ve got ’em right now.

That’s the easy way out. You wouldn’t like an alternate band with Ray Charles?

DM: Ray Charles would completely edge me out, so no. I’m gonna go up and sing something after Ray Charles? I don’t think so. I want to do some music with Jimmie Vaughan playing guitar. For what I do, Mike Joyce, my bass player, is absolutely the best. He’s not loud, but you can hear everything he says, and he puts it all right where I would if I could play bass.

I’ve seen this happen too many times: A bunch of superstars get together and make a record, and it sounds like shit because they don’t really play together. Young people growing up, they play everything they know in every song, and that’s natural, and then you suddenly realize that less is more. You can’t play loud or too much, but you have to do that with likeminded people. I have a band right now, and we just all take a breath at the same time. And I like it a lot.

BK: I’m not even gonna think about it. I want Earl Palmer on drums, I want Nick Lowe on bass, I want Buddy Miller on guitar, and I want Merle Haggard singing. Austin de Lone on keyboards. I’m just gonna sit there and noodle. I’m gonna do anything that I damn well want.

What’s your desert island album?

DM: Percy Mayfield, His Tangerine and Atlantic Sides. The Tangerine Band was Ray Charles’s band, and Ray Charles is playing piano on it. Percy Mayfield was one of Ray Charles’s favorite singers. He wrote, “Hit the Road Jack” and all… but I’ve got a CD; I don’t think you can buy it anymore. It is flawless. Flawless. Completely flawless. The most perfect horn arrangements that I’ve ever heard in my life. Guitar amplifiers were little 12-watt amps. You couldn’t play loud, so it’s not big and crashy and aggressive; it’s just solid and perfect. A friend of mine gave it to me about seven years ago, and I can’t stop listening to it still.

BK: I’m just gonna tell you this for fun; somebody famous said, “I would want to have William Shatner reciting Bob Dylan. It’d drive me so crazy; I’d hollow out my legs and make a canoe.”

But I’m gonna go back and say Home of the Blues Vol. 1 and 2 on the Minit label. I’ve often thought to myself that those two records I got back in ’68 or ’67 might have been the two best records I’ve ever gotten. You ask me five minutes later, and I’ll tell you something else. But I need a CD player on that island, none of this record stuff. I’m too lazy for records.

[…] from his peers, including collaborators and tour mates like Sting, Ronnie Milsap, Carole King and Delbert McClinton (Thorn has headlined McClinton’s Sandy Beaches Cruise in recent years). Thorn’s humor and […]

[…] his peers, including collaborators and debate friends like Sting, Ronnie Milsap, Carole King and Delbert McClinton (Thorn has headlined McClinton’s Sandy Beaches Cruise in new years). Thorn’s amusement and […]

[…] Percy Sledge’s timeless “When A Man Loves A Woman;” Albert Collins (electric guitar), Delbert McClinton (harmonica) and Willie Dixon (vocals) on a hypnotic “Hoochie Coochie Man;” Dixon and Koko […]

[…] missed Bill Kirchen, one of the best guitarists on the planet, and the opportunity to hear his new music and old […]