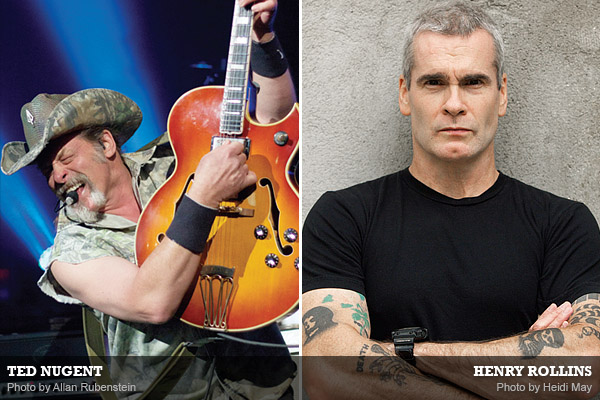

TED NUGENT

Known for his wild man stage persona, Ted Nugent—born December 13, 1948 in Detroit—grew up in a strongly Christian household under a disciplinarian Army staff sergeant father. “There’s quite an unlimited list of ingredients that goes into where I got here today, but I guess it can be summarized with ‘discipline,’” Nugent said. “I was disciplined to do the best that I can do or I wouldn’t get dinner. My allowance was food, and that’s only if I cut the lawn perfectly.”

Nugent soon found the guitar, and by the early ’60s, he was playing his wild brand of Detroit rock in several local bands. Upon forming the Amboy Dukes in 1965, Nugent took his raw rock beyond the local borders and released several albums with the Dukes, scoring a Number 16 hit with 1968’s “Journey to the Center of the Mind,” which the anti-drugs-and-alcohol Nugent claimed he didn’t know was about being under the influence (his teetotalist views are often cited as an influence on the no-drugs-and-alcohol lifestyle so common to hardcore punk, epitomized by Ian MacKaye and Henry Rollins).

After a few more albums with a rotating cast of musicians that backed him, lead singer/guitarist Nugent officially dropped the Amboy Dukes name in 1975. Without missing a beat, Nugent went on an incredible solo run, releasing one multi-platinum album per year between 1975 and 1978 while cementing his status as one of rock’s most intense and energetic guitar showmen. Following a steady stream of solo albums throughout the ’80s, Nugent went multi-platinum again with supergroup Damn Yankees (including Tommy Shaw of Styx) in the early ’90s. In 1995, Nugent returned to solo work with Spirit of the Wild, after which he turned his attention to his incredibly rigorous touring schedule, which has topped out at over 300 shows per year and has yielded many live albums over the past two decades.

In addition to his work as an author, columnist, USO performer, radio host, television personality, actor, philanthropist and conservative/humanitarian/Second Amendment activist, Nugent still maintains that rigorous touring schedule. This year’s two-disc live album, Ultralive Ballisticrock, captures a 2011 performance in Pennsylvania. That title tells you pretty much all you need to know about Nugent’s sound.

HENRY ROLLINS

Born Henry Lawrence Garfield in Washington, D.C. on February 13, 1961, Henry Rollins was never without the trademark aggression and energy that made him one of punk’s most iconic frontmen. Hyperactive and prone to fighting in school, the adolescent Rollins was put on Ritalin and sent to a naval prep school, where he honed the incredible drug- and alcohol-free work ethic that has informed his entire life.

“I’m a guy of complete middle-class upbringing. I never missed a day of food growing up. My parents worked, and I always had Spaghetti-Os and ravioli at the ready. And then I joined Black Flag, and all of a sudden, I learned what hard work was,” Rollins said. “We worked like crazy people, and we didn’t eat all the time. I haven’t had a straight job since.”

His career began in earnest when—after working jobs ranging from liver sample courier for the National Institutes of Health to manager of a Häagen-Dazs to the frontman for State of Alert—he became lead vocalist for Black Flag in 1981. With this seminal hardcore punk band, Rollins truly made his name (quite literally too, switching from Garfield to Rollins upon joining). With Black Flag, Rollins moved to Los Angeles and impressed—and intimidated—larger and larger audiences with his singularly intense stage presence.

Following a few years of Black Flag alienating many fans with their ever-changing style and Rollins alienating the rest of the band with his always-intense stage demeanor, the band broke up in 1986. Rollins, with his passionate work ethic in high gear, moved right along, releasing three solo records and two records with the newly-minted Rollins Band in 1987 alone. After a steady flow of releases, Rollins Band broke through commercially in 1994 when they appeared at Lollapalooza and their album Weight reached the Billboard Top 40. The following year, their label declared bankruptcy, and Rollins turned his efforts elsewhere. The band regrouped a few years later, then endured some lineup changes before completely dissolving in 2003.

Since then, Rollins has focused all of his efforts on his non-musical projects. As a Grammy-winning and constantly touring spoken word artist, author of more than 25 books, regular columnist for LA Weekly, USO performer, NPR host, television host, actor and liberal/humanitarian activist, even Rollins’ legendary work ethic might sometimes be strained—but don’t count on it.

![]()

What are you listening to right now?

Ted Nugent: I’m the master of flatlining. If you’re going to have the intensity with which I pursue all my passions, you really do need to charge the batteries, so I’m good at sitting and petting Labrador Retrievers with Mrs. Nugent. I still listen to James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis—I still like the originators. They had a little bit more piss ‘n’ vinegar. But just moving through the woods, listening to dogs, the birds—the hawks and owls and song birds—this is a healing power of nature that I not only cherish, but I desperately need. Tonight, I will turn my amps on, and people will blow up, and so will I, and God knows I love it. It’s a balancing act.

Henry Rollins: These days, I’m listening to a lot of music from Scandinavia, specifically Finland, a lot of instrumental drone and strange, ambient folk music. I don’t listen to vocal music as much as I used to; I’ve been going more toward noise music—bands like Wolf Eyes.

What was the first record you ever bought?

What was the first record you ever bought?

TN: Walk, Don’t Run by the Ventures. I was in the 9-, 10-, 11-year-old bracket.

HR: A double cassette box of Grand Funk Railroad’s Live Album. It’s the first thing I bought when I had earned money from delivering newspapers. I don’t know why I bought it. It kind of looked interesting. I was in fourth grade.

What was the first instrument you played?

TN: My Aunt Nancy was a stewardess, and when I was four or five or six, she brought home an acoustic guitar that someone had left on the plane. It had five working strings—barely—and one really noisy, nasty bottom E string, which was my favorite. And I would just beat on it, emulating Chuck Berry or Bo Diddley, which is what I’m going to do tonight in Tucson.

HR: [Rollins sang and does not play an instrument.] I don’t have any music in me. There would be those who would disagree. HR: You can be in a band and not be all that musical.

What brought you to the instrument you now play?

TN: My cousin had an electric guitar and a little Magnatone amplifier, and I had to sneak a stab at it because he didn’t like me playing it. By the time I was eight, my dad got me an electric Epiphone, and I was both wonderfully happy that I got an electric guitar, but brokenhearted that it wasn’t a cutaway, which all my heroes played. My dad forced me—that’s called parenting—to practice 30 minutes a day. I had to take this timer off my mom’s stove, and I better make some guitar sounds for 30 minutes. Then I started taking lessons by Joe Podorsek, who started getting my fingers in the right place. Then the rockets kicked in, and here I be. At my 6,000th concert in Detroit a few years back, Joe got up on stage and played the same boogie woogie and honky tonk music that we’d played 50 years earlier. What a great moment.

HR: I had records because of my mom. Music was always on: Bartók, Brahms, Bach, Beethoven, Miles Davis, Streisand, Hair, Godspell, Hello Dolly, Porgy and Bess—all of that was part of the house. She turned me onto the Doors, Jimi Hendrix, Dylan, the Beatles, Guthrie, Carole King. We would go to the record store up to three nights a week, so by fifth grade, I had Cheap Thrills by Joplin. My favorite record was Hot Buttered Soul by Isaac Hayes. I was a pretty eclectic little dude. Punk rock music was the music that really kind of answered the call for me. I used to always go see Led Zeppelin and Ted Nugent and big bands like that and buy their records and enjoy them, but none of the lyrics were angry like I was.

Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

TN: I’m a big fan of Dave Grohl and a huge fan of Steven Tyler and all those guys, and Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top.

I wrote with Carole King and Desmond Child at a songwriters’ get-together organized by Sting’s manager. They flew me in because they liked the edgy, hard, cocky lyrical approach to my grinding guitar songwriting style. It was fun.

HR: I co-wrote one time, as a favor. That’s about it. I wrote lyrics for a long time, very obsessively, and then one day, it just left. Other people—Tom Petty or Dylan—just write forever. These days, I certainly howl, but it turns more into an angry, politically-charged, 1,000-word essay, but not a lyric.

What musician influenced you most?

TN: Those original, black, spirited, defiant, rebellious musical masters. Chuck Berry was one of the first masters of Les Paul’s new electric guitar; he pretty much laid down the gauntlet, and I don’t think anybody’s ever beat him since. Way before the British Invasion, I was tuned into the black guys that created the British Invasion. Without Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry and the Motown hits, there would be no Beatles.

The breaking of the slavery shackles—both literally and figuratively—gives us a little bit more velocity. I stop and think what they call “punk rock” today…give me a break! Let me know when they can walk in the vapor trail of Little Richard, which was punk. You’ve got a gay black guy with a pompadour singing about tutti frutti with your white girl. Fuck you.

HR: The Stooges. That is the ground zero band for me. The single musician: Ian MacKaye; we’re best friends for about 40 years now. And H.R. from the Bad Brains, because that, to me, is one of the ultimate frontmen of all time.

What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

TN: I was just a 10- or 11-year-old kid, and we would play these Chuck Berry mutilations and make up lyrics and jam at this little malt shop. I would get free malts, and I go, “This is cool as hell”—because I had a paper route at the time.

HR: In the summer of ’81, Black Flag was going to play New York, so I drove up to see them. It’s 3:30 in the morning, and I have to be at work in seven hours. They had a song about going to work, called “Clock In,” and Dez, the singer at the time, said, “This is for Henry, because he’s got to go to work,” and he just stuck the mic out and said, “You sing it.” I jumped onstage, and I did the song the way I thought it should be done. I remember distinctly the audience looking at me like, “Damn!” I gave the mic back to Dez, got in my car, took a shower in the work sink and scooped ice cream for 12 hours. The next day, I get a phone call from one of the band members, who said, “We liked your singing. You want to come up here and audition?” I’m looking at $3.75 an hour or audition for a band. I said, “I’ll be up there tomorrow morning.”

At the audition, I literally took my left hand and pinched my right arm because I thought I was dreaming. Whatever songs I knew, I sang. Whatever I didn’t, I just kind of yelled along. I sat in the lobby, and they came out ten minutes later and said, “You’re in.” I say, “In what?” They go, “In Black Flag.” I go, “What do you mean?” They said, “You’re the singer in Black Flag.” “Me?” Twelve hours before, I was wearing an apron, scooping ice cream. They said, “Do you want this job or not?”

Back in D.C., I went up to my boss, Steve, with a quavering voice and said, “Look, I’ve got to go for it.” And he said, “Yeah, you do. Good luck. If it doesn’t work out—and I’m sure it won’t—you can have your job back.” I met the band in Detroit—I still have the bus ticket. I got to the venue before they did and said, “I’m the new singer in Black Flag.” I felt like a fake.

Steve still comes to my shows, and whenever he shows up, it almost brings me to tears. We disagree on everything politically. When I bust on some Republican—they make it so easy—I can see him turning red. But he and I have a deeper friendship than all of that stuff.

What was it like the first time you didn’t have to carry your own gear?

TN: After I graduated in ’67, the Amboy Dukes were playing 300 concerts a year—probably maxed out at 350 by ’69, ’70. I was the only clean and sober guy. I didn’t know anything about that drug world, but I sure noticed the guys slept a lot, and I wasn’t about to let them drive. I would load the truck, drive the truck, change the tire, change the oil, solder the guitar cables, buy and replace the speakers, buy the band’s food, cook it, do the laundry…at some point, I’m doing everything.

I would threaten my booking agent: “If we have a day off, I’m taking your children hostage.” We had to make money. You get a place with electricity, we’ll plug in and play. The spiritual price is high. Even though I’m ridiculously healthy and high energy, I think we can both agree with the greatest philosopher of all time, Dirty Harry, that a good man knows his limitations. If I’m good for anything, it’s because I know my limitations.

Up until my first solo album, I was still humping gear, booking hotels and running the entire operation until I got a call from [future manager] David Krebs, and he started telling me what we’re going to start making every night now, and I went, “Well, that’s cool as shit. I’ll get a crew.”

HR: That actually happened in 1989 in Australia. This crew came out and grabbed our gear. We’re like, “What are you doing?” “Oh, we’re your road crew, mate!” And we’re like, “…OK…” And then you get to a point where you have a full-on road crew, where you’re paying salaries to multiple people, and that group of ne’er-do-wells takes up the tour bus…I was on the road for 12 months last year. It was 190 shows in 19 countries.

Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

TN: I’d like to have James Brown as my singer. I already have the best drummer, Tommy Clufetos. I’ve jammed a bunch with John Entwistle, and it was like a musical orgy. That guy is a living, breathing, grunting rhythm. For horns, let’s go with the Stax/Volt guys, and I’m going to have Steve Cropper on standby just in case I want a rhythm guitarist.

HR: I think it would be really cool to be able to combine like a ’70s-era version of Parliament Funkadelic—you have a very young Bootsy Collins and his brother as your rhythm section, Eddie Hazel on guitar—and someone more avant like John Zorn, and see where that would take you.

What’s your desert island album?

TN: James Brown’s Live at the Apollo is not just a musical whiplash, it’s a spiritual cleansing. You can just close your eyes and see him doing the splits, kicking the mic stand and doing a 360.

HR: The Black Album by the Damned. It’s just a nice piece of happy-place listening. Here Come the Warm Jets by Brian Eno. It’s a perfect album, mixing the avant and the pop. Putting on a record…it’s just a simple joy, and it’s what I’m going to be doing tonight.

Be the first to comment!