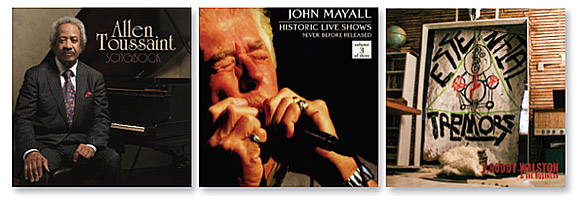

Allen Toussaint

Allen Toussaint born January 14, 1938 in New Orleans, is enormously responsible for the New Orleans sound, and for music of every genre. His behind-the scenes work has made him an industry legend. From his work with the Band, Paul Simon, Little Feat, Dr. John, Glen Campbell, Elvis Costello and Paul McCartney to his latest album in 2013, Toussaint’s touch has been magic. Toussaint himself says, “That’s my comfort zone, a producer: the one behind the scenes who organizes, who finds the songs—in my case, I write them; finds an arranger—in my case, I arrange them; finds a piano player—in my case, play. Before Katrina, performing artists would come to New Orleans and record; when Katrina happened, New Orleans was under martial law for a while, so I migrated to New York. This really isn’t me. As a producer, I send me out there and give myself instructions: ‘go out there and do this.’ I tell myself to establish a character sometimes.”

John Mayall

Born on November 29, 1933, John Mayall grew up near Manchester, England. Initially attracted to jazz and blues, once he heard boogie woogie, he found his musical calling. After two years at art school, he took a graphic design job at a department store, feeling like a music outsider, until Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies opened a London blues club. Already 30 years old, Mayall quit his job, moved to London and put together the Bluesbreakers. Over the next few decades, with an unerring ear for talent, Mayall brought in Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood, Peter Green, Mick Taylor, Coco Montoya, Walter Trout and Buddy Whittington, among others. Along the way, Mayall and his revolving cast of Bluesbreakers charted dozens of albums and set the standard for electric blues. Now 80 years old, Mayall leads a foursome (no longer called the Bluesbreakers) and plans to release an album of new material this May, fueled by the same vigor with which he pioneered the British blues boom 50 years ago.

J. Roddy Walston

J. Roddy Walston, born February 14, 1981 in Cleveland, TN, formed J. Roddy Walston & the Business in 2002, and soon gained a reputation as an explosive live act, combining southern roots, hard rock and soul, all held together by his own pounding piano. Following three EPs, several lineup changes and a move to Baltimore, the Business released their debut album, Hail Mega Boys, in 2007. Their self-titled follow-up (2010) earned them a spot on Elmore’s “11 Artists to Watch in 2011” cover story, and we haven’t quit watching them—at festivals like Bonnaroo, Lollapalooza and Austin City Limits. Now, the Business has just released Essential Tremors, so called because Walston himself suffers from the condition. We caught up with Walston the day before the band played a major event at the Barclays Center as part of New York’s Super Bowl festivities.

![]()

What are you listening to right now?

Allen Toussaint: I’m really busy with projects, so I’m not listening very much, but if I’m flipping channels, I can’t pass up the Three Tenors without stopping.

John Mayall: I never listen to music in a hotel room, and I seldom listen to music at home, so my only touch with music is when I’m on the road, and then we make our own. I don’t really listen to much music—never have, really.

J. Roddy Walston: I’ve been on a kick with early Robert Palmer, like Pressure Drop and Sneakin’ Sally, and earlier Lowell George. I can pretty much, at any time, put on pretty much any Zeppelin record.

What was the first record you ever bought?

AT: My mother bought an Emerson record player when I was a boy, and they gave her two things—that’s called a lagniappe in New Orleans—two records: one a swing record with Benny Goodman’s Orchestra, and one classical with Paul Weston’s Orchestra. With my own money, I bought Professor Longhair when I was about 12.

JM: Albert Ammons, Shout For Joy; I was probably about 14. It was boogie woogie.

JRW: R.E.M., Automatic for the People. I was 11.

What was the first instrument you played?

AT: Piano. For a little while, I flirted around with the guitar and, in school, I played trumpet for a little while, but never got good enough to make the senior band. I played the violin for about a minute. As long as I was playing 16th notes where you couldn’t hear how it really sounded, it was good, but when I slowed down and played soft things, I could tell that I was on the wrong train.

JM: Either the ukulele or the guitar. I don’t remember when it was. My father wasn’t a professional musician—it was a hobby—but he played guitar and had a guitar around the house. Keyboard second, harmonica third.

JRW: I had a brief encounter with drum lessons in fifth grade—ten or something. That was only for a couple of months. I was a nervous wreck at all the lessons. Then I played cello for a little bit and then guitar.

What brought you to the instrument you now play?

AT: My aunt had an old upright that she wasn’t using. The ladies in my family thought it was dignified for a young lady to play the piano or violin, even though we were poor as Job’s turkey. It was sent to my house for my sister, when I was about six and a half. I saw this big piece of furniture over there, and I went over and touched it, and it just gave me a really pleasant sound, as opposed to trying to play a trumpet for the first time, which sounded like a small elephant. My sister had a piano teacher who spanked her hands, so her lessons were short-lived, but she was a smart girl and learned quite a bit of early theory.

I had already begun to pick out little simple melodies that I heard on the radio, and I understood the structure of the piano. My sister could tell me, “This E you’re playing here is there on the page,” so that got me thinking beyond picking out things by ear. My mother enrolled me in Junior School of Music, but she gave up because she knew boogie woogie had me.

JM: Our friend’s parents had a piano. I never learned to read or write music. I write songs by ear; I wouldn’t know how to write it down.

JRW: I came the long way around to piano. We had a piano in the center of the house. It wasn’t sacred, but it was definitely treated like, “This is not a toy.” Being in bands and writing, I got tired of just the guitar, bass, drums and as I started to write, I realized I was playing more piano parts. I picked up tricks from my grandmother, who was really a gospel kind of country honky tonk piano player. My mom’s whole family was super musical. They would load up the car and go to these churches that would put on gospel concerts. It was a point of pride that my grandmother never took any money because it was at church.

I’m pretty passionate about writing and I was spending a lot of time every day at the piano, basically the same way I taught myself how to play guitar, which was by writing songs. I probably approached everything backwards. My wife is an opera singer and proficient in piano, and sometimes she’s kind of like, “What you’re doing makes no sense.”

Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

AT: I never think about writing with people. Fortunately, Elvis Costello and I wrote together, but he is one who is self-contained as well. He’d write up to a point and say, “Where would you take it from here?” It’s a luxury to be with him. He carries so much information; he is broad in any genre, and he gives them all equal respect.

JM: My mind doesn’t really work that way. Songs are written out of your own experience.

JRW: Bob Dylan would kind of be unreal, although I don’t know what you’d add to Dylan. I love Randy Newman and I have a few songs that I think would be pretty awesome to have him mess around on. There are so many people who would be awesome to work with.

What musician influenced you most?

AT: Professor Longhair, and a gentleman named Ernest Penn. He played in an era where if you played a string instrument, you played everything with a string on it: If you played piano, you must play banjo, guitar, bass. He was a master at all of that, but he was a banjo player, really. By the time he got to me, he kept a half a pint of liquor in his pocket and stayed happy all day long, with no teeth in his mouth. He heard a piano, and he saw me outside and he said, “You know, I’m Professor Ernest Penn. I’m a banjo player, but I don’t have a banjo.” My uncle had an old banjo gone into decay, and this man took an old beer tray and put a back to it and went to the drug store and got strings and he played the banjo, and it was magic. I brought him in to play the piano, and he played the stride. I had never seen that. It was just me and him in the room, yet he just played like there was a whole audience. When he’d get through, he’d jump up from the piano and say, “Hot the mighty Sam!” I’d look in amazement, but that was part of his ritual.

Maybe two years after I met him—I was 13—we came back from a family trip and they told me he had set on the side of his bed and shot himself. I’m not sure why. But after it all happened—I believe in things beyond just sitting here—he probably came through that neighborhood for me. From then on, the piano had no ends on either way. It had no height. It didn’t end at the top. The rooms were bigger. Life was bigger.

JM: There are so many influences that you can’t narrow it down. I’d be loath to give you examples, because I’d be leaving somebody out. There are a million great musicians who have all had an influence over me and I wouldn’t put one over the other.

JRW: The combination of what I think are really great lyrics, aggressive music but also really poppy songs with Nirvana was definitely a big thing for me. John Bonham, also, because I realized the distinction between being technically great at your instrument and also being musical… particularly for me, because I really approach the piano as a percussion instrument more than a melodic one.

What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

AT: I thought I’d always be a musician. It hadn’t dawned on me that you had to be paid when I decided this. Me and Dr. John was playing on recordings—I was always pianist and he was guitars, and every now and then I’d hear something that we had played on come on the radio, and I did think, I’m a part of that. Just to hear it on the radio, that was a biggie.

JM: Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies started off opening up peoples’ ears to blues music in clubs. I just figured this is what I played all my life. I was about 30, and this was an opportunity to go down to London and join in. You put one foot in front of the other, and try to do your best.

JRW: I’m probably still waiting for that moment, but there are two, so far. I was in eighth grade; it was the year Kurt Cobain died. The school banned playing Nirvana songs, but none of the teachers knew those songs, so every band played a Nirvana song, but said they wrote it. These ninth graders literally smashed all their instruments on the gym floor. Me and my friend literally turned to each other and said, “We’re starting a band tomorrow.” There weren’t talent shows allowed at our school anymore after that. Then, the first time I could actually pay my bills with money I made from playing was kind of a watershed moment.

What was it like the first time you didn’t have to carry your own gear?

AT: I still carry my own bags quite a bit. I came to New York from New Orleans alone, so I’m fine with that.

JM: We don’t really have professional help on the road; we still carry our own stuff and set up ourselves. When I was 30 and the British blues things started, we all travelled around in vans because we were in England, and it’s not that big of a place. Today, you fly internationally, LA to London, and to the first gig in Germany or Holland, then travel by bus until we are finished with the tour—there’s no difference.

JRW: I don’t know yet. We are going literally to play the Barclays arena and we’re going to be setting up our own gear and breaking it down afterwards.

I don’t think the unions are going to let you do that at Barclays.

JRW: Yeah, a few times we walked into a building with guitars under our arms and some Teamster shows up like, “Woah dude, you’re stealing my job.”

Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

AT: I’d use Herlin Riley on drums. On bass, Trae Pierce—this guy is killer. I’d have Elvis Costello play guitar, because of all that he is and cares about and knows, not just what he plays. I’d have another guitarist as well, Jimi Hendrix, but that will change the sound of the band a little bit, because I’d be in his band.

JM: I have got the band that I want. Greg Rzab [on bass], Jay Davenport is the drummer, Rocky Athas is the guitar player, and that’s the best band I could possibly come up with. I know what I want in a band, and the camaraderie that goes with it, and for me, it’s a very simple operation—it always has been. I know what I’m looking for, but it can’t be explained. It’s an instinct, an indefinable quality. It touches you emotionally and excites you, and you just go for it because you know it will work.

JRW: I love Led Zeppelin; they make my favorite music but they didn’t write my favorite song. Normally, I very much love a structured song and, in particular, a big chorus. So it would probably just be Zeppelin with Kurt Cobain in front of them and influencing the songwriting, to be honest. Definitely John Bonham on drums, Kurt Cobain for songwriter/singer. But to go more complex, funkier, I’d love to see Keith Richards and Levon Helm and Leon Russell together.

What’s your desert island album?

AT: Donny Hathaway.

JM: Music is full of variety, and variety in life is what you need. One day it could be one thing, and the next it could be something else.

JRW: I really love Randy Newman, Sail Away. That record I can pretty much listen to endlessly.

[…] can check out the full list of tour dates below, as well as an in-depth interview about musical influences featuring lead vocalist, guitarist and pianist J. Roddy […]