by Ali Kaufman

Musicians’ art—performance—seems to be the polar opposite of fine art—painting, photography and so on. Music is all about creating on the fly, evolution and doing the same thing repeatedly but differently. Fine art is about getting it as good as you can, and letting it stand, untouched, for centuries. Why, then, are so many musicians also fine artists? What makes the musician/fine artist create a static work? The following eight painters, photographers and sculptors explain…

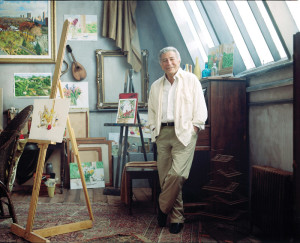

Tony Bennett

Sure, Tony Bennett has 17 Grammys and two Emmys. He marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. from Selma to Montgomery. He has charted albums in each of the last seven decades—and his artwork will hang in respected museums for decades to come.

While Bennett left his heart in San Francisco, it started beating in Astoria, Queens, where he one day picked up chalk and started drawing a Thanksgiving scene on the sidewalk, a work which caught the eye of his school’s art teacher, James MacWhinney. MacWhinney became Bennett’s mentor, teaching him to paint with watercolors and, on Saturdays, opening Bennett’s eyes to the rich culture and artistry of New York City and its museums. Today, some of those museums now host Bennett’s own paintings.

While many are now familiar with the fact that Bennett is a well-respected painter, just how well-respected is evident in the fact that three of his paintings are part of the permanent collection at the Smithsonian Institute: a 2002 portrait of Ella Fitzgerald, a 2006 painting of Central Park and a watercolor portrait of his friend Duke Ellington. The United Nations has commissioned Bennett for two paintings, and he has works in both the Butler Institute of American Art and the National Arts Club.

The majority of Bennett’s works employ watercolors, which are easier to take on the road—or into Central Park. “I often paint in Central Park since it is the view from my window at home and am sure some people on the benches might stay a bit longer if they realize they are a subject of a painting or sketch,” Bennett said. Whether he is working en plein air or working from photos he has taken, it is the way the light plays upon a given scene that most catches his interest and inspires him. Bennett finds inspiration everywhere, particularly in interesting human subjects—beyond this portraits of the famous. While some of these subjects don’t even know they’ve just been sketched or painted by a world-famous artist, some do. “Often, I will sketch a waiter in a restaurant and then give them the sketch,” Bennett said. “I have been known to leave sketches on the tablecloths from time to time.”

Bennett’s eye for portraits extends from waiters to Duke Ellington, and sometimes himself, though Bennett considers self-portraiture to be an exercise. It’s only fitting that this man of such great talent and generosity would focus so much more on the outside world and on others rather than on himself. He and his wife, Susan founded Exploring the Arts (ETA), whose programs are designed to help keep the arts alive for students in the face of school budget cuts. ETA has its own school (the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts in Astoria) and has partnered with 17 public high schools, 14 of which are spread across New York’s five boroughs, with three more in East Los Angeles.

Bill Kreutzmann

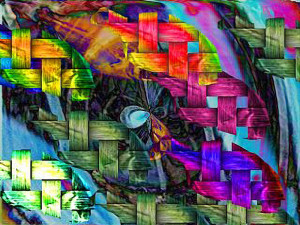

“It all comes from the same place; it’s just the medium that changes,” Bill Kreutzmann said, reflecting on the creativity that fuels both his music (with the Grateful Dead and a handful of groups since) and his visual artwork. Ever since Jerry Garcia introduced Kreutzmann to computer-generated artwork in 1994, Kreutzmann has never looked back. At first, playing around with Photoshop was a way to entertain himself, but it soon became much more. In addition to playing a tremendous amount of shows with the Grateful Dead, Kreutzmann began steadily creating both computer-generated art and paintings. While these works are manna to the Deadheads who love to speculate upon every nuance of the band’s music, Kreutzmann sees his work simply as the product of one man and his imagination.

Today, inspired by the surroundings of his Hawaii home, Kreutzmann’s art has taken a hands-on approach, turning away from the computer-aided designs of his earlier work. Kreutzmann takes his canvases outside, among the orchids, and lays them down flat while music with a great beat (preferably something by the Dead) plays loudly in the background. He then dips his soft-tipped drum mallets (“they absorb the acrylic paint best”) in paint and beats down on the canvas. The results are remarkably Jackson Pollock-esque yet completely his own. In art, music and life, having fun seems to be Kreutzmann’s modus operandi.

Grace Slick

Grace Slick’s interest in visual art started long before her incredible musical career began with The Great Society and Jefferson Airplane. As a child, she was always drawing, and with talent and follow-through over many years since, she now enjoys an art career that sees her work sold to collectors around the world. For Slick, the process of creating those works was always completely natural: “There is a sameness of entering into that creative space, whether it’s painting or performing,” Slick said. “If someone said, ‘You can’t paint anymore,’ then I would write; if I couldn’t do that, then I would design sets, and so on—you find an outlet for your creativity.”

With their brightly-colored, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland themes, Slick’s paintings and sketches consistently conjure up one word: fun. Moreover, they draw you in and, upon closer inspection, make you realize that this is not your traditional telling of the story. These paintings illustrate why Alice may have been seeing the things she saw and feeling the way she did—and include Alice’s partners in crime, including, of course, the White Rabbit. That rabbit has been following Slick around since the beginning, from birth (she was born in the year of the rabbit) to scoring a hit with Jefferson’s Airplane’s “White Rabbit” and through the present, in her paintings. For Slick, Alice’s White Rabbit represents curiosity—and if you have the cojones, you follow it. Life is short, according to Slick, and when you get old, it’s not what you did that you’ll regret; it’s what you didn’t do. She did not learn to ride a horse; she did not go to the Middle East; she did not do Jimi Hendrix or Peter O’Toole—and maybe, she thinks, she should have.

Transmuting these themes into visual art, Slick works with acrylics, pen and paper, scratchboard and pencil. She’s also done several pieces in the Japanese style of Sumi-e, the practice of doing more with less. Slick likened the style—a somewhat minimalist technique that employs black inks and fine brush techniques similar to those used in East Asian calligraphy—to peeling an onion, stripping away the extraneous and keeping only that which truly matters. No matter the technique or the tools, or even the medium, be it painting, sketching or music, Slicks believes, “It’s not hard to understand my style; it’s colorful, straightforward and in your face. I have the same style on canvas as I do at the microphone.” Obviously, it’s working for her.

Commander Cody

George Frayne, aka Commander Cody, knows full well that it’s lousy to do an entire 4’ x 4’ painting in a color that you end up strongly disliking and having to paint it over. So, one painting at a time, with plenty of prep work in Photoshop first, and with a healthy dose of tinkering right until he can finally call a painting done, Frayne creates the works that have won him awards and acclaim since before he formed Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, the musical act for which Frayne is best known. “Music was a challenge; visual art is something that I have always been doing,” Frayne said. Having exhibited his work at dozens of galleries and shows from the ’60s to the present, Frayne’s outstanding creations most recently graced the pages of Art, Music & Life, an oversized book covering much of his catalog.

Unlike Bill Kreutzmann and many other musician/artists, Frayne does not use background music while he paints. Instead, he prefers the process of creating to be more like meditation; “It can be a great doorway to the alpha zone,” Frayne said. According to him, it’s like being awake and dreaming—this is where some of the best ideas are born, both visually and musically.

Using this process, Frayne has created a varied body of work, prominently including colorful portraits of fellow music greats (and accompanying stories of his connection to them). His most frequent subject is Muddy Waters, whose big, wide grin, according to Frayne, exudes a myriad of feelings equaled only by Duke Ellington. Beyond portraiture, Frayne’s painting can be far more unconventional. “Horse Power II,” a life-sized fiberglass horse sculpture he painted in 2007, spent a summer installed outside New York’s Museum of Natural History, where, years ago, Egyptian art captured the young Frayne’s imagination.

Bryan Adams

In contrast to many musician/painters, musician/photographers seem to have more definite ideas about the results they want from their craft. The photographers included here seemed like the kids that colored inside the lines, while the painters not only colored outside the lines, and sometimes went right off the page. The photographers do take risks, but the medium of photography lends itself to a more organized creativity.

This is especially true of Bryan Adams, whose latest photographic work, a coffee table book entitled Wounded: The Legacy of War, grabs the viewer with its stark reality. The book compiles portraits taken of British soldiers who were wounded and disfigured while serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Over the course of four years, what started out as a way to document the price paid by these servicemen and women became book length material. Adams did not end his project with the publication of the book; The Bryan Adams Foundation, which receives every penny earned by his photography, will put on an event this year to benefit wounded service personnel and War Child, an organization that helps children who have been in war zones.

Wounded represents but one facet of Adams’ photographic pursuits. His work published in magazines like Zoo and Vogue includes striking, polished images of the famous and fancy, including Boy George in Jean Paul Gaultier for Zoo. But, no matter the style or the subject, this self-taught photographer always brings the interesting and engaging perspective of a man who’s always been surrounded by cameras, whether he is in front of the lens or behind it.

Andy Summers

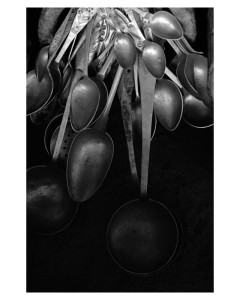

Andy Summers, the guitarist for the Police, is currently touring with his newest group, Circa Zero. While his long and varied music résumé includes work with those two bands and several others, the constant for Summers, creatively, is his love of black and white photography.

He still remembers the rainy day in New York in 1979, already touring with the Police, when he bought his Nikon. Summers, inspired by the films of Truffaut and Fellini that affected him as a teenager, has always preferred to shoot on film and in black and white, which he believes elicits the greatest emotional response. For years, Summers documented a world to which few are privy, and did so in a way that even fewer could get away with. Shooting behind the scenes with the Police, Summers captured the rock star experience from the inside. These photographs were eventually published in 2007 as I’ll Be Watching You: Inside the Police 1980-83. Summers’ two other books include Throb (1983) and Desirer Walks the Streets (2009).

Following up on his last book’s theme, his “Mysterious Barricades” exhibition is a darker collection that pulls from his huge catalog of photos taken when he ventured out, after finishing a show, into cities around the world. In the hands of Summers, the project is far deeper than a simple travelogue: “It’s not about liking this photo or that one; it is thematic and a story I want to tell with a body of work, depending on the setting,” he said. The exhibition opened this April in Hollywood before beginning its world tour. Next time Summers tours (if not before), he’ll be off to the “dodgiest” areas he can find to capture more images—the kind you must dig for and take a bit of risk to bring home.

Moby

Moby prefers daybreak to nightfall because he “likes the world when no one is paying attention to it.” As a serious photographer since well before his debut album, Moby is constantly paying attention.

Born in New York and raised in Connecticut, Moby was always surrounded by visual art. His mother painted, one uncle sculpted, another photographed for The New York Times. For Moby, finding his life’s work in the art world was not a huge leap. A book of photography by Edward Steichen that was lying around the house, as well as the punk rock photography so prevalent during Moby’s youth in the late ’70s/early ’80s, pushed him toward photography.

He has since built a large and varied oeuvre, just one particularly striking group of which is his crowd shots, many taken from the stage during a show, giving us concertgoers a way of connecting with the superstar’s perspective. But, as much as Moby is a superstar, he still understands the perspective from the crowd. He still remembers his first concert—Yes at Madison Square Garden in 1978—just as memorable to the 14-year-old Moby for the music as it was for the fact that it was on a school night. The experience of being part of that large and exciting crowd stuck with him. As Moby sees it, we human beings spend much of our time trying to protect our autonomy and private space, then, for fun, we pack ourselves like sardines into crowds—the individual getting lost in the movement of the group, which can be just as unhealthy as it can be wonderful. This entity, one group comprised of many separate pieces, is what Moby strives to capture.

Moby’s spontaneous crowd shots differ greatly from the staged and stylized photos that make up large chunks of his 2011 book, Destroyed and his latest exhibition, “Innocents.” These collections take inspiration from the surrealist artists that Moby admires. In particular, his use of masks (the hallmark of “Innocents”) is intentionally disconcerting. According to Moby, masks can be beautiful or terrifying, strange in what they suggest even though they are mere pieces of plastic or rubber—a simulacrum with the power to elicit a very real response, much like great photography itself.

Julian Lennon

He snaps shots on the set of the forthcoming film, The Price of Desire, a book of his photography is in the works, and he has scheduled another job as on-set photographer for a film at the end of the year; Julian Lennon’s latest adventures in photography are certainly keeping him busy—and excited. Even with so many different projects in the works, Lennon insists that “each collection or session really needs to have its own look and feel. The pictures that are chosen for a project need to really shine and elicit an emotion from the viewer.”

Although Lennon’s interest in photography goes far back, he didn’t consider it a career goal when he got his first Polaroid at 11 years old as a Christmas present from May Pang and Dad, John Lennon. “They were always taking lots of photos and it was fun for me, as I was really starting to get passionate about music at that point,” Lennon said. Today, with successful exhibitions under his belt and more jobs clearly lining up every day, photography is indeed a career for Lennon.

Lennon’s charitable work with his White Feather Foundation has expanded his photographic horizons. While he’d previously been working mostly on either coast here in the States, the foundation’s charitable work takes Lennon all over the world, an experience he’s been diligently documenting with his camera—from the water wells that are saving lives in Kenya and Ethiopia to the indigenous tribes of Colombia. But whatever his subject matter, Lennon considers himself a “student of life,” with new things to learn every day. In order to express that experience, Lennon has worked not only in photography, but in painting, sketching and sculpture—all in addition to his music. His most recent album, 2011’s Everything Changes, seamlessly combines his various artistic pursuits, with each song tied to a different photograph and video, all created by Lennon himself.

Whether photography, filmmaking, painting, sketching or sculpture, Lennon is ever optimistic, unfazed by the knee-jerk reaction of those who may not take an established musician’s artwork seriously: “You have to love your work, put it out there and hope the world does too.”

[…] Click here to read about Bennett exploring his other surprisingly unexpected artistic affinities. […]

[…] recent years, Bryan Adams has devoted more and more of his time to his award-winning photography. However, on September 30, Adams will release Tracks of My Years, his first studio album since […]