By John Kuroski

[T]he official Michigan Historic Site plaque posted on the front lawn of 2648 West Grand Boulevard in Detroit begins, “The ‘Motown Sound’ was created on this site.” And it was. From 1959 to 1972, an assemblage of off-duty jazz musicians backed a smattering of doo-wop castaways and erstwhile church choir singers to create the unique brand of pop soul named on that plaque. That music is, of course, some of the most enduring of the 20th century, and was created almost exclusively in a converted photographer’s studio in back of a nondescript white house.

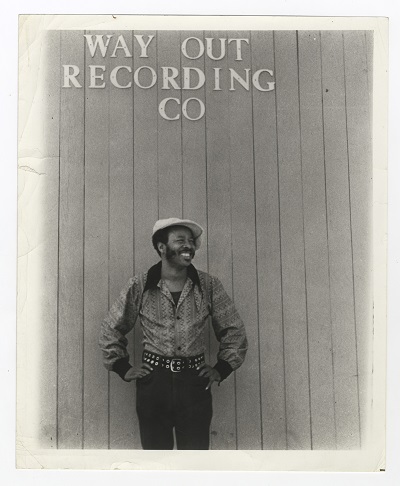

Some 80 miles across Lake Erie, back behind another nondescript house in another Factory Belt city—Cleveland—sat another soul/R&B recording studio, this one in a converted barn. This, the studio of Thomas Boddie, served as the first of many local studios that produced tracks for Way Out Records. Founded in 1962—just three years after Motown—the label’s offices likewise occupied the first floor of a small, humdrum building. Unlike Motown, after hours, the interior knob of Way Out’s front door was tied to a string. The other end of that string was tied to the trigger of a wall-mounted shotgun.

Over the next 11 years, Way Out produced a few dozen records, charted none and discharged that shotgun only once.

Way Out’s output includes most if not all of the stylistic shadings that encompass what we know as the Motown sound: lilting pop gospel (the Exceptional Three’s “Unlucky Girl”); urbane, jazz-inflected soul (Volcanic Eruption’s “Red Robin”); mellifluous late doo-wop (Lou Ragland’s “Never Let Me Go”); friendly light funk (Norman Scott’s “Ain’t That A Heartache”) and more. While at least half of the Way Out oeuvre is truly first-rate (and now compiled for the first time as The Way Out Label, part of the Numero Group’s “Eccentric Soul” series), the label’s success never came close to matching that of the white house across the lake.

Way Out’s artists only ever briefly popped their heads above the tides of musical history, always receding back into the forgotten depths. There was the night in 1954 when the Drifters plucked the Hornets’ Johnny Moore from Cleveland’s Circle Theater and into the big time (upon joining the Drifters, Moore did end up singing lead on a few of the lesser-known hits that bookended the Ben E. King era). There was Lou Ragland’s quick stint singing with the Dominoes in 1965, and the three months he spent playing bass with the O’Jays in 1968. There was the brief distribution deal the label itself had with MGM in the mid-’60s (courtesy of the financial and promotional help of football star and Cleveland hero Jim Brown), lasting for just seven records.

Neither those seven records nor any of the several dozen others Way Out ever released climbed too far up the charts. Meanwhile, the former photographer’s studio attached to the white house in Detroit was cranking out chart-topper after chart-topper. However, that success had not only to do with the goings-on of that white house, but also with the houses surrounding it.

While even casual Motown fans can probably picture that white house, “Hitsville U.S.A.,” even serious Motown fans probably don’t know that, in the seven years following its founding, the company bought seven adjacent houses, to hold its various business offices, and one more across the street. That house, 2657 West Grand Boulevard, was home to Motown’s artist development department, which was—more than the imported-from-the-auto-plant production ethos, more than the extraordinary songwriting talents of Smokey Robinson, Holland-Dozier-Holland and many others, and even more than the singular star power of Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder and beyond—perhaps the greatest factor in Motown’s enormous commercial success.

When in Detroit, all Motown artists were required to visit, for two days a week, the artist development department, Motown’s finishing school. There, under the tutelage of director Maxine Powell, artists learned not only things as basic as how to walk, but also that walking wasn’t really what they should be doing in the first place—“Everybody walks,” Powell once said, “but I teach how to glide.” Thus Powell prepared Motown’s stars—many of whom, according to her, came “from humble beginnings, some of them from the projects…some were rude and crude”—for a pop audience, and for a white audience.

If we’re to reductively characterize sweeping cultural sea changes, and if we’re to uphold the oft-repeated theory that Motown’s greatest cultural achievement and most effective commercial engine was the desegregation of pop music, then 2657 West Grand might have been the most important house on the block. While, like the plaque says, the Motown sound was created at Hitsville U.S.A., the label’s ultimate destiny was also forged across the street.

Either way, artist development was certainly the thing that Motown had that the others, like Way Out—and dozens of other labels scattered across dozens of other cities—did not. But what Way Out (and not necessarily those dozens of other labels) had that Motown did not was a humanizing, ramshackle charm absent from the sparkling hubcaps and sculpted fins of Motown’s gorgeous, immaculate product. Way Out’s records weren’t just wonderfully rough around the edges; they didn’t always have clear edges in the first place. Consider the frenzied, mile-a-minute vocal delivery of the veritable sermon that takes over the Soul Notes’ “I Got Everything I Need,” or the live wire guitar at the climax of Volcanic Eruption’s “I’ve Got Something Going For Me,” far louder than it should be and exactly as loud as you want it to be.

These moments are where the waters of history part to allow Way Out in. This is the product of a perfectly scuffed label that simply whited out the “MGM” on its records when that distribution deal fell through, a label that saw its biggest stars depart for greener pastures only to find that those pastures don’t stay green for long, a label that tied a door to a string and that string to a shotgun.

All photos courtesy of Numero Group

Hey John Kuroski!

I finally took the trip and broke on through to the other side of Elmore magazine – the online side (now the ONLY side!) – and this was the first piece (column!) that I read. Once again you’ve done more than merely entertain but have also educated, enlightened, incited and inspired me with your writing. This WAY OUT Records story is FAR OUT! Now I can hardly wait to hear the music!!! So, when may I please borrow your copy of “The Way Out Label” from Numero Group’s “Eccentric Soul” series?

Dennis McDoNoUgh!