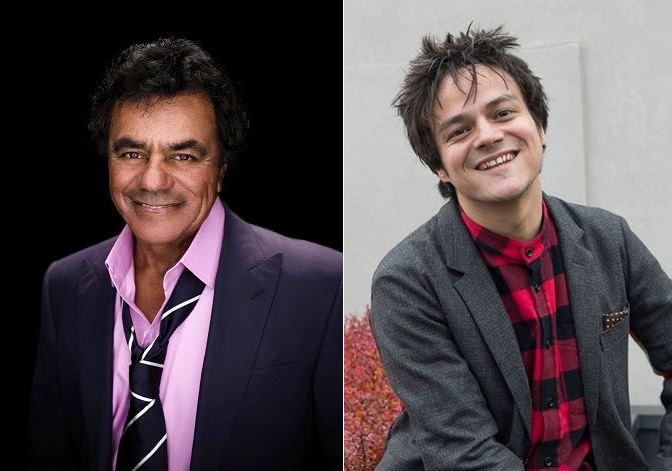

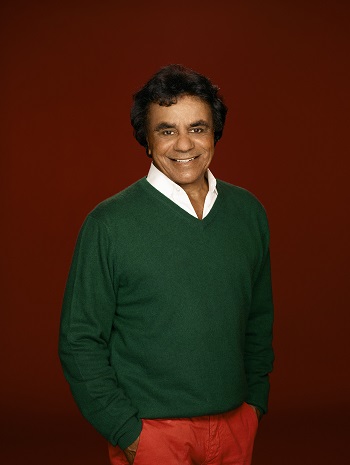

Johnny Mathis

Born in Gilmer, TX on September 30, 1935, Johnny Mathis learned his love of music from his father, Clem, a sometime singer and piano player, who taught him songs and routines, encouraged his talents and set him up with his first vocal coach at the age of 13.

While attending San Francisco State University on a track-and-field scholarship, Mathis worked weekends singing at a local nightclub, where he was spotted by George Avakian of Columbia Records. A gifted athlete as well as a performer (he set the San Francisco State high jump record), Mathis passed up the chance to try out for the 1956 Olympic team, choosing instead to head to New York to record his debut album, Johnny Mathis.

Following the release of that album, Mathis teamed up with famed producer Mitch Miller, who helped him develop his signature style as a romantic crooner, allowing him to record some of the greatest hits of his career, including “Wonderful! Wonderful!” and “It’s Not For Me To Say.” The hits kept coming (and coming, and coming…) as 1958’s Johnny’s Greatest Hits spent a record 490 weeks (that’s almost a decade) on the Billboard 200. Over those 490 weeks and beyond, Mathis charted with dozens more albums and singles, demonstrating his mastery of genres ranging from pop to jazz to standards. All told, Mathis’ 350 million records sold make him the third most successful recording artist of the 20th century. Along the way, he conquered the world, singing not only in English, French, Italian, Spanish and German, but in Portuguese and Hebrew, and addressing his Filipino fans in Tagalog. With accolades including a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, several Grammy Hall of Fame inductions and the 2003 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, Mathis’ mantle is surely crowded.

Today, at age 79, retirement doesn’t seem to be on Mathis’ mind. Following the November release of The Complete Global Albums Collection (compiling the ten—yes, ten—albums he released between 1963 and 1967; buy here), Mathis is currently on a nationwide tour with dates scheduled throughout 2015.

Still, for all his fame, Mathis is a charming, unpretentious guy. “After my mom passed away, my dad would stay with me,” Mathis recalled. “I used to bring people like Nat [King Cole] around to my house, and sometimes I’d bring some of my athlete buddies over. I was a high jumper on my track team, and so was Bill Russell on his, and we were buddies in San Francisco. When he started to play for the Celtics was just about the time I started singing. I would bring people to the house to meet my dad, who was the nicest guy in the world. Dad would say, ‘John, how did you meet these people?’ That was my biggest thrill—bringing people home and letting my dad meet them.”

Jamie Cullum

Born August 20, 1979 in Rochford, England to an Anglo-Burmese mother and an English father whose mother was a Jewish refugee from Prussia who sang in Berlin nightclubs, Jamie Cullum was raised on diversity. It shows in his music, which freely combines standards and originals drawing on rock, hip hop, jazz and Tin Pan Alley, all with an improvisational twist. Until his university days, Cullum played guitar and occasional piano at home with older brother Ben, and in rock bands in bars and clubs. Still rooted in rock and dance music at the time, Cullum took a turn toward jazz after hearing Herbie Hancock.

While at Reading University, he used his student loan money to record his first album, Heard It All Before, a collection of jazz standards, in 1999. The album’s success put him on the radar of industry veterans, and his second album, 2002’s Pointless Nostalgic, was a critical hit.

The following year, after signing with Universal, Cullum released Twentysomething, already cementing his status as the top selling jazz artist in UK history. From there, Cullum continued to grow as an artist, releasing three more studio albums (Catching Tales, The Pursuit and Momentum) between 2005 and 2013, garnering plenty of accolades along the way (including a 2009 Golden Globe nomination for Best Original Song for his titular contribution to the Clint Eastwood film, Gran Torino).

Throughout, Cullum has continuously found ways to evolve, drawing on collaborations with artists across diverse genres for inspiration. He has lent his unique, soulful style to covers of tracks from musicals (My Fair Lady’s “I Could Have Danced All Night”), pop hits (Rihanna’s “Don’t Stop the Music”) and rock classics (Jimi Hendrix’s “The Wind Cries Mary”). Ever the renaissance man, Cullum also hosts an enormously popular weekly jazz broadcast on BBC Radio 2, is an accomplished amateur photographer (a skill he used to document his latest US tour and create the artwork for his forthcoming album, as well as open an exhibition in London), magazine curator and a family man (he has two daughters with his wife, food critic and former model Sophie Dahl).

Currently, Cullum is back and forth between England and New York City, where he previewed his upcoming album at the Blue Note Jazz Club and has spent several evenings opening for Billy Joel at Madison Square Garden (he’ll open for Joel at MSG again on January 9 – buy tickets here). Cullum’s seventh studio album, Interlude, is slated for US release on January 27 (pre-order digital here and physical here).

Elmore: What are you listening to right now?

Johnny Mathis: I listen to a real potpourri. I’ve been listening to a lot of Brazilian music. I sing the songs in Portuguese just to practice my facility of the language. When I was 12 or 13 years old, I was listening to Erroll Garner, Oscar Peterson, all these people coming through San Francisco, and I have a lot of that around.

Jamie Cullum: Electronic music got me into jazz; there’s quite a few good electronic albums that have come out recently, like Flying Lotus. DJ Shadow, A Tribe Called Quest, the Beatnuts, Madlib…all that stuff brought me to jazz. Also, I just got the new deluxe version of The Velvet Underground, which I really love.

EM: What was the first record you ever bought?

JM: I was so poor. I depended on my brothers and sisters and my dad, who had a little bit of money, to listen to whatever music they brought in the house.

JC: At eight or nine, I was very much into the British rock of the time, so my early records, you may never have heard of: the Wedding Present, Ned’s Atomic Dustbin. If you’re remotely interested in understanding me as a musician, it’s important to know that I was a total record geek long before I was a musician.

EM: What was the first instrument you played?

JM: I don’t really play. I can play the piano enough to learn my songs, and read the notes.

JC: The piano, but actually it was not the first instrument I fell in love with playing— that would have been the guitar, definitely. When I was about five or six, I showed no interest or aptitude in piano, and then didn’t have anything to do with music until about 11 or 12, when I got into the guitar. We had a cheap kind of dollar store acoustic, and my dad had an electric from the time when he was at university and everyone wanted to be in the Beatles. We had an old department store amp and made a drum kit out of cardboard boxes. I grew up in an atmosphere where my parents encouraged creativity, and loved that, but it was also very much, “you need security and safety.” Around that time, I was discovering AC/DC, classic blues and musicians like Stevie Ray Vaughan. And then it became all about Kurt Cobain, Soundgarden and Rage Against the Machine.

EM: What brought you to the instrument you now play?

JM: My teacher tried to get me to learn the piano while I was studying voice with her, but I had so many other activities: I got involved in track and field, and did pretty well, so all of my time was taken up. That’s my excuse for not learning to play the piano.

JC: There was a piano in the house, and the piano came back around the same time as I was discovering bands like Jurassic 5, Cypress Hill, A Tribe Called Quest and the Beastie Boys.

EM: Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

JM: I have such admiration for these composers who write wonderful melodies and clever lyrics, and I am not talented in that regard. It took me a long time to realize this because I used to sit and fantasize and say, “I can do this,” and of course I couldn’t. Over the years, I have changed a few notes and words, but I always consulted the composer or the writer, and they’d agree to it. I remember I sang an alternate note in “Evergreen” by Barbra Streisand, and she liked it. She made them change the music.

Over the years, I have sung peoples’ songs wrongly. In 1956, you went in the studio, you had four songs to do in three hours, and whether you sang them well or correctly, they were down there. If you signed a contract, the record company had to release the song. You were trapped. “Can I do it over again?” “Nope, time’s up.” I’ve listened to some of my early stuff and say, “Oh no!” Fortunately, there weren’t many, but believe me there were a few, and sometimes they come back to haunt me. If your successes are bigger than your mistakes, I think people forgive you a little.

JC: Tom Waits, Prince, Irving Berlin. I would love to write with Sufjan Stevens. Can you make them all happen, please?

EM: What musician influenced you most?

JM: My dad was a singer but he had a big family, so he never pursued it as a profession, but he was the person that I wanted to please. He had seven children, but he always had time for all of us and he was just my best buddy in the world. He said, “Son, if you really want to sing, let’s find a teacher.”

When I was young, I got a chance to meet people like Miles Davis, Oscar Peterson, Erroll Garner and Dave Brubeck, who all went through this little nightclub called Black Hawk. My dad or older brother would take me, and I got to meet all of them because we couldn’t go while they were serving booze, so we went in the afternoon on Sunday when they were rehearsing. Most of them were so kind, and they all remembered me after I had my first success.

JC: I didn’t know famous people. I knew people who did music as a passion, something to do on the weekends, and they were amazing musicians.

Herbie Hancock, because I wasn’t listening to any classic jazz at all, then I heard Herbie Hancock’s ’70s stuff, with didn’t sound too far away from the rave and drum and bass music that I was listening to in a disused warehouse house in Bristol. They’re doing stuff in America now that I was doing when I was 15, 16. There was a real link there between the electronic music and the hip hop music and the dance music that I was listening to.

I would say Ben Folds is of pretty huge importance to me, just the idea that piano could be an instrument of great rock ‘n’ roll power. “Punk rock disease,” as he calls it. Joined a lot of dots up for me. Harry Connick Jr., no question, and probably Nina Simone, because she operated in jazz, but with a rock ‘n’ roll edge, an intensity and a slight imperfection to her singing.

EM: What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

JM: I never came to that realization. It wasn’t really an “aha” moment when I discovered I can sing and everybody be damned, I’m going to do it. I was a child of my dad, the most cautious man I’ve ever known. He kept saying, “Son, don’t get so excited; this is just something we’re doing for fun.” People like Louis Armstrong wanted me to go on the road with him and my father said, “No way.” Quite a few of the jazzers with big bands thought that people would like to hear me sing because I was a little beyond what most kids could do at that age vocally. Every time I’d come home: “Dad guess what! This guy heard me sing! He wants me to go with him on the road!” He’d say, “Sit down a minute, son; I need to talk to you.” Then one day, when George Avakian, the head of jazz at Columbia Records, heard me sing at this little jazz club in San Francisco, he said, “Son, I think maybe this might be the tine that we should put all your eggs in one basket and go for it.”

Things happened slowly. George Avakian wanted me to become a jazz singer but of course I was not and never would be. We did an album. No one played it. But Mitch Miller was across the hall from George Avakian, and he was in charge of popular music, people like Rosemary Clooney and Tony Bennett. And he asked me if I would like to try to sing something a little different. They gave me a stack of music about as tall as I was, and I picked out four songs: “When Sunny Gets Blue,” “Wonderful! Wonderful!” “It’s Not For Me To Say” and “Warm and Tender,” a song that a kid by the name of Burt Bacharach wrote. He was in the studio, driving me crazy, showing me how to sing it, standing over me, hitting me on the back. That was the way things got started.

JC: I guess I decided that my teenage armor was going to be as the musician. Everyone needs that—you know, they’re either sporty or clever or attractive. I was none of those things. So I was gonna be the musician, the mixtape maker, the record collector and the guy who would carry the guitar around whether he could damn well play or not.

I didn’t really think I would be a musician for a living until I was 21. And by that time I was doing five, six gigs a week. I was in the last few months of university; I’m trying to think about what job I want to do and I thought, “I’m already doing a job,” and I loved it. In the back of my mind, I thought that it might be a feature of my life, but no one was telling me I was a prodigy or, “Oh my god, you should pursue this.”

I made a CD with my student loan. I knew I could make it back, because after any gig I did, people would say, “Do you have a CD for sale?” We made a CD in two or three hours, cost me about $500 to make and a bit more to press, and I sold every single copy and doubled my money. It was called Heard It All Before, just ten standards. In my last year in university, I was playing gigs the night before my finals. I missed my graduation ’cause I got a gig on a cruise ship sailing around the Greek islands. You know, 21, single, playing an hour and a half a night.

I had a place to crash in London; a friend of mine had a basement flat, just real cheap. I thought, I’ll give it a couple of years, be able to pay the rent, have some fun and then figure out what I’m gonna do. And I never stopped.

EM: What were your first perks of success?

JM: I think the thing that I needed most was a conductor to conduct my music. I was basically a singer but I had to talk to musicians all the time about what I was going to sing, what the tempos were, what key I was going to sing. Finally I found one. His name is Frank Owens, and Frank was my first full-time piano player conductor. Frank was a wonderful pianist who was probably mostly self-taught.

JC: In the early days, the first tours with Amy Winehouse, I was partly driving myself; we were still carrying our own gear. The tour after that was when Twentysomething became big; we were decked out with trucks full of gear and we had a tour bus.

When you turn up in San Francisco or New York and see your name, and your tour bus stops outside and you see a queue of people outside—these are the moments that you really feel it. That was pretty amazing.

I started traveling business class about six years ago. I think it started to be real for me when I realized there’s free catering. (Laughs) Isn’t that pathetic?

EM: Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

JM: First of all, I’d call Quincy [Jones], and tell him to get everything. I don’t care who you get, just get a good band together. He is such a big part of my life, in that I’ve admired his tenacity and his brilliance over the years and being able to work with all kinds of different people, and be successful at it.

On piano, Hank Jones. I think I first heard him when he was accompanying people like Ella Fitzgerald. It was done absolutely without any effort, totally relaxed and beautiful. It swung, funky, brilliant. The thing we strive for—all of us—is to make it look easy. I’d have Dizzy Gillespie playing the trumpet, I’d have Miles [Davis] playing. Ben Webster playing saxophone. Erroll Garner. EM: These are jazz players. They can play anything. They have that ability to make it interesting by not going to the holy grail. They invented the holy grail.

JC: James Gadson, who played drums on Bill Withers’ “Use Me”—one of the greatest drummers of all time. Him or Earl Palmer of New Orleans. Charles Mingus on acoustic bass. Definitely have Hendrix on guitar. Maybe he could trade with Stevie Ray Vaughan. Brian LeBarton, who plays keyboards for Beck and with Feist.

EM: What’s your desert island album?

JM: Anything by Ella Fitzgerald. This is a woman who, in my estimation, was as good as anybody that ever walked this earth, as far as a singer is concerned. The command of her voice was just extraordinary. Just when you thought there was nothing else up there, she’d come out with another little note, a little higher, a little softer.

JC: Donny Hathaway’s Live, or I would take the first Velvet Underground album. I love Ella Fitzgerald, and if I want to learn a song, I listen to Ella’s version. But there’s something too good about it, that I found that if I try and take from it, I would just end up feeling sad.

[…] Johnny Mathis and Jamie Cullum Over those 490 weeks and beyond, Mathis charted with dozens more albums and singles, demonstrating his mastery of genres ranging from pop to jazz to standards. All told, Mathis' 350 million records sold make him the third most … He has lent his … Read more on Elmore Magazine […]

johnny mathis one of the all time greats, the master of love songs and Christmas songs.

At the age of 79, still singing and touring.

He has left is mark in the history of music.

[…] Johnny Mathis and Jamie Cullum JM: I don't really play. I can play the piano enough to learn my songs, and read the notes. JC: The piano, but actually it was not the first instrument I fell in love with playing— that would have been the guitar, definitely. When I was about five or … Read more on Elmore Magazine […]

[…] Johnny Mathis and Jamie Cullum While at Reading University, he used his student loan money to record his first album, Heard It All Before, a collection of jazz standards, in 1999. The album's …. I had a place to crash in London; a friend of mine had a basement flat, just real … Read more on Elmore Magazine […]

I was always in love with him and his music to this day…love you Johnny.

Jan 11 2015 — Just saw Johnnie Mathis in concert 1 hour ago in Ft Pierce Fla. He is still a great professional and Legend. His voice is still fantastic and strong, sounds just like the CD s we would listen to on a weekend evening. Really happy we went to see him, he rates as one of the great masters and legends of the 60s and 70s, who’s still out there giving it his all. Thanks Johnnie for a great evening.