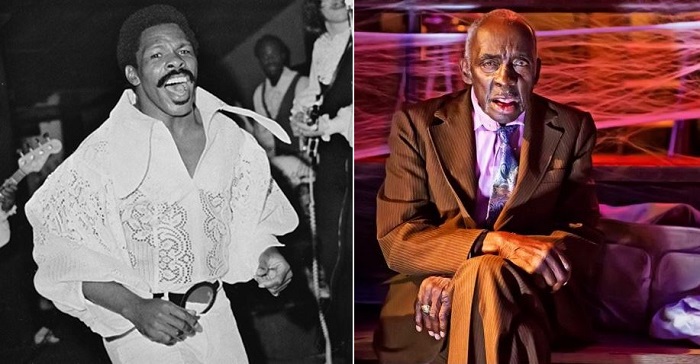

Born less than 300 miles and one year apart, Lloyd Price and Leo Welch followed very different career trajectories in the music business. Price went straight for rock ‘n’ roll, radio and mainstream success, while Welch played solo, sticking to traditional North Mississippi blues and playing his gigs in church.

Their timelines also differed by more than half a century: as a teenager, Price wrote the first million-selling record ever sold in America or in the world, “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” and had written and released “Stagger Lee, “Personality” and “I’m Gonna Get Married,” (all of which topped the pop and R&B charts) before he turned 30. Leo “Bud” Welch began playing guitar at ten or eleven years old, but stuck close to home, working on a farm and playing in churches; he launched his professional career at 81.

Here are their influences.

Lloyd Price

Lloyd Price, affectionately known as “Mr. Personality” after one of his million-selling singles, was born in Kenner, Louisiana on March 9th 1933. Price grew up with a background in music, being formally trained as a boy (yet—unlike so many Southerners of his generation and before, including Leo “Bud” Welch—Price never once sang in church). Working at his mother’s restaurant, he was discovered by Fats Domino’s producer, Dave Bartholomew, while performing “Lawdy Miss Clawdy.” In collaboration with Bartholomew and his band, the record propelled Price into the music business.

“When I first started recording it was race music. None of my records ever had race on it and ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ was the first youth record played on all radio stations across America and across the world.” The song has been recorded 178 times.

Returned from serving in the Korean War in the ’50s, Price and two other men formed KRC Records, and Price also released tracks through ABC Records from 1957 to 1959, including “Stagger Lee,” “Personality” and “I’m Gonna Get Married,” which topped the pop and R&B charts. In 1962, Price formed Double L Records with Logan, where they signed Wilson Pickett. Following Logan’s murder, Price founded the new label, Turntable, and opened a club of the same name in New York City.

Fifteen of his records have become Top Ten R& B hits. Price toured with Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and Gary U.S. Bonds in 1993. In 2005, Price famously performed with soul legends Jerry Butler, Gene Chandler and Ben E. King for “Four Kings of Rhythm and Blues” tour. Price was inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998 and the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame in 2010. In 2011 he released his autobiography The True King of the Fifties: The Lloyd Price Story.

In 2015 Price’s memoir, sumdumhonky, was published. In it, he explores the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, and how he came to realize that no matter his level of success, race was an issue, especially in his early days in New Orleans R&B, and how he has struggled with the relationship between success and race.

Despite the difficulties, however, Price rock and rolled out of Kenner and into the mainstream consciousness of the 1950s through his music, and is still singing today as one of the best R&B vocalists of our time.

Leo “Bud” Welch

“I’m 83. I was born in nineteen hundred and thirty-two, the 22nd day of March, I have a twin sister named Cleo.”

Born in Sabougla, Mississippi, Leo Bud Welch started playing music at a young age. In 1945 he started sneaking away to play his older cousin’s guitar, and by 1947 Welch was performing publicly. He missed an audition with B.B. King, but looking back, Welch thinks he was too young back then. “I tell people now if I’d have went on then, no telling where in the world I might be. But the Lord knows best. And I think now is just my time.”

Holding down a full-time job cutting logs on a farm, Welch performed at churches or on weekends in surrounding counties around Bruce, Mississippi, where he know lives. He also occasionally opened or played during intermission for better known acts.

After 1975, he began playing mostly gospel with his sister and sister-in-law as the Sabougla Voices, performing locally for family and friends. For over 65 years Welch remaining unnoticed by most blues fans, but in 2013 he was secretly recorded while performing at a birthday party. His manager, Vencie Vacaro, told us:

I’ve known Leo all my life. My 50th birthday was coming up, so I hired him to come and play at my birthday party, and secretly videotaped it. I called up Fat Possum Records and told them I had some footage on a guy I think they would be interested in. [General Manager] Bruce Watson saw about three minutes of that video , and asked if I could get Leo down to the office. I told him it took me two years to get this far, but I called Leo up and said, ‘They’re interested in meeting you,’ and he told me he didn’t have a way up, so I told him I ‘d take him. Bruce a set up a session in the studio for two weeks later, we did about three of those sessions about two weeks apart, and that became Sabougla Voices. Six months after Sabougla Voices came out, we went back in and started working on the blues album.

In 2014, two months before his 82nd birthday Welch debuted Sabougla Voices through Big Legal Mess Records, and released his sophomore album, I Don’t Prefer No Blues, in March of 2015.

In the old North Mississippi days, when Welch was young, bluesmen usually didn’t have a drummer, it was just a bluesman and his guitar or harp—some didn’t even have an instrument, they sang a capella, “Today, the artist has help and doesn’t have to work quite as har,” Vencie explained. “Leo, however, still does it the old way, and when he plays, it sounds like there are two or three people onstage, but it’s just him.”

Pickin’ it old school, Welch himself says, “I’m Leo the Lion. They say Leo the Lion will keep a cat away from your house.”

Elmore: What are you listening to right now?

Lloyd Price: I went and heard Frank Zappa’s son, Dweezil, at the Beacon Theater. Impressive. I hadn’t heard anything I was impressed with for a long time.

Leo “Bud” Welch: I listen to the radio, and whatever’s on. I listen to different groups, different bands, where I’m playing at, and I may sing some of the songs they sing, but I do things my way. I do things the Leo “Bud” Welch way.

EM: What was the first record you ever bought?

LP: My mother had a sandwich shop. She sold fish and potato salad on the weekends. She had a jukebox in there and first it played first 10 records, and then 20. I knew every song on the jukebox, the A and the B side. I would sing along with Louis Jordan, he was like my first king, Louis Jordan and then there was Roy Milton and Camille Howard and all these were race records. I knew the songs backwards and I would dance when people come in the shop and throw nickels and dimes on the floor every time she didn’t run me away.

LBW: I never did buy too many records, but my first cousin did. He’s eight years older. We listened to Sonny Boy Williamson, folks like Muddy Water’, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore Jame’, Jimmy Reed, all them old blues guys. I play it all. I play gospel, blues, play what I call hillbilly songs, like Ernest Tubb’s “Walking the Floor Over You.” I used to listen to the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights, out of Nashville, Tennessee, back in the ’50s-some odd.

EM: What was the first instrument you played?

LP: When my brother went into the Coast Guard he had a flugelhorn and a trumpet. I tried but never did play well on the trumpet. I couldn’t get my armature right. I didn’t have enough air—I was too small, but my heart was in it. I just had to do something to get on the jukebox, to find a way out of Louisiana, and the easiest way for black people at that time—and I guess and white people—was either in sports or entertainment. That had seemed to be the way out.

LBW: Guitar. After I started the guitar, I took up the harmonica, and I could blow that like I’d practiced. I can play fiddle, bass guitar, keyboards enough so I can accompany myself. I always had music in my bones, from the day I was born.

EM: What brought you to the instrument you now play?

LP: My mother had this old, broken-down piano in the sandwich shop, and I tried to play that piano. I kept doing that, and my little brother Leo later became a drummer. During lunch breaks in high school we would going the auditorium. I’d bang on the piano and he’d beat on some cardboard boxes and later it turned into the first little teenage band in my town in Kenner, seven miles short of Louisiana. We started playing locally at a club, and we packed the joint although we knew only three or four songs

LBW: My first cousin, R.C. Welch, had a guitar; I learned the guitar from watching him. He ordered a guitar by selling garden seed, four dollars a pack, and got his first guitar, an acoustic guitar. We didn’t have no post office, we were out on a rural route. We knew that mailbox wouldn’t hold that guitar, and we know about what time it was coming in, and me and his baby brother Orlando went to the mailbox, and when we got back with it, he told me and Orlando he didn’t want us messing with his guitar. When he and his girlfriend would go out someplace—“courting,” the older people called it that in the old days—we’d get to wailing and bamming on it. One day he came in and we were playing, and he said , “I thought I told you boys not to mess with my guitar.” And we said, “You did.” And he said, “Well, I ain’t going to say nothing else to you any more, ’cause y’all are playing better than I am.” I been playin’ it ever since. I could play everything at 15 year’ old like I play now. Actually I started at 10 or 11 year’ old.

EM: Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

LP: All the hits I had, I wrote alone. After 60 years, I just wrote a song with my now conductor, Charles Choice. I like Bruno Mars and Smokey [Robinson]. I would need to hear why would I want to. I believe what sells commercially is things people understand. If you give people something that has that kind of power or structure, it will work for you.

LBW: I write songs, and I be playing them, but I don’t write ’em down. The music just comes out of my ears, and I be singing. It’d be best to write it down, so you be able to stay in the right place, like if you’re going to record it, and come in with your same bridges, the same position, but besides that…it takes me a month to write a song now, I write slow. When I was in school, we didn’t have no computers or all that kind of stuff, no mics, no amplifiers for guitars, either. We had to play the old way.

EM: What musician influenced you most?

LP: At the beginning, Louis Jordan, who wrote “Caldonia” and a gang of other songs; he was my hero. Then Erskine Hawkins, who had a song called “After Hours,” such a big, big record. It was just the piano, but I heard the creativity. I thought Lennon and McCartney were just incredible creators. These guys were on the ball.

LBW: The one influenced me most was a Muddy Waters song. I’m talking Muddy Waters pre-Chicago, not after they took the music to Chicago and screwed it up. My music is pre-Chicago. Muddy Waters influenced the way I play, not the way I sing. I like B.B. King. The one that influenced me most was my cousin, R.C. Welch. My style is totally different. I sing the Leo “Bud” Welch way.

I wouldn’t be where I am now if it weren’t for R.C.. Told me how to tune, to play; I can play with a slide or a bottle on my finger. I don’t use no pick. I don’t want no pick in the way. I use my fingers, all these fingers. I used to play with a pick on my forefinger, but I put a clamp on the neck of the guitar about three or four frets down.

Elmore: How have things changed?

LP: The music started to integrate the young kids in this country like they had never ever integrated before. During the early ’50s, anything a black kid or black man did in this country was against the law, including going to the supermarket and getting in the front of a line or going in the church in the front door, and here was a music that was breaking the barrier of all of those old traditions. Young kids, coming together by the hundreds! Coming to see me to my house there in Louisiana, their parents scared to death. Nobody could understand what was happening.

LBW: I started out playing the blues, and they didn’t allow guitars in church around here, back then. They called it the Devil’s Music. Now, every church you see has a guitar, a piano, a keyboard, or something, and it don’t sound like church no more. They thought the guitar was the instrument of the Devil, they didn’t allow it in church.

EM: What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

LP: Like I said, there was only two ways out of my town: sports or entertainment, and I knew I could dance. I figured I dance my way be out of there. There was no Jackie Robinson—five years after him, I did “Lawdy Miss Clawdy.” It was just out the question for young uneducated black people doing anything other than going to work. It was mandatory: if you didn’t go to school, you went to work.

LBW: I was playing in two different churches. On the first and third Sunday, I play at the Sabougla Baptist Missionary Church, and on the second and fourth Sunday at Double Springs Baptist Church. They told me they’d give me $20 for my gas in Sabougla, but $50 over there at Double Springs. Now I have more money than I ever had in my life.

I wrote B.B. King and asked for an audition. I thought he might could play my hotel room. At that time it wasn’t but ten dollars a week, or something like that. I never did have an audition with him. He was a poor boy, too. He was “B.B. King and the Beale Street Blues Boys,” and used to play here in Bruce, where I’m living now, 25 miles south of Oxford, at the Blue Angel Ballroom, a juke joint in a county that’s been dry since 1907. This old black guy, Otis McCain, had it, and he served bootleg whiskey and beer. Had baseball games on Sunday afternoon, dances on Saturday night at the juke. B.B. King, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Johnny Hayes, Ernie Ford, Cyril Duncan, all them cats were together when they come down here.

Reason I said yes [to a music career] two years ago was because Vencie paid me for playing at his birthday party, and he said he would book me at some places where I could go and make some money. That’s when I decided to give in, ’cause I wasn’t making no money. I had retired in 1995, but I was working for a dollar a day on the farm, from sunup to sun down. He said I can book you in places where you can make some money.

EM: What was it like when you first felt success? Maybe the first time you didn’t have to carry your own bags?

LP: On the day that I heard myself on the radio my brother and I were riding in my father’s truck. My father was a plumber and we had worked with him, and on our way home, the radio was on and the DJ Okey-Dokey was on, and he said, “I’m going to play the song one more time by this kid from Kenner, Louisiana, ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy.’” He didn’t call my name, and my brother said, “Didn’t you have something like that?” I didn’t know it was me. I was the only one that knew I had made the record—I didn’t tell my mother or my father because I wasn’t supposed to leave home.

I didn’t have the bus fare, but the bus driver let me ride down to the studio for free and gave me transfer to get to the studio because I had delivered ice at his house one time, and he thought I was a nice boy.

I always drove myself. I didn’t care how far, I always drove. I did have people taking care of my clothes, but I never felt like let’s say a James Brown. I had 11 back-to-back number one hits all over the world. I just always felt that it was such a blessing to be able to do what I got to do, and get out of Kenner.

LBW: The best thing is try to make every gig we can make and make more money. That’s the new life, the way I see it. It started about two years ago. It changed my life greatly. I got two vehicles, two vans, one paid for, one not. I wouldn’t have had it working for a dollar a day on the farm. If I’d been in church, I wouldn’t have that. Sometimes, back in those days, I used to have to thumb a ride to get to the church. I’d stand on the road with a rope sling on my guitar hanging on my back. Now, I’m getting to be a road warrior. I enjoy traveling.

EM: Who would you like in your rock ‘n’ roll heaven band?

LP: Frank Zappa would be my guitar player, Earl Palmer would be the drummer, Fats Domino would be on piano; Stanley Banks, who plays with George Benson, would be on bass. Randy Choice would be on piano. Mick Gaffney who plays good stuff with a band here in New York has probably one of the greatest guitarists I’ve ever heard; he hasn’t had any records but he’s been on everybody’s records, he’s just an incredible player. If King Curtis was still living, he would be my lead saxophone player, or Frank Foster with Count Basie. Miles Davis and Maynard Ferguson would have to be on the trumpet section, Al Grey on trombone and on baritone that big guy called “Beans” Bowles; these are guys that I think were just some of the greatest players I ever heard. Slide Hampton would be in the trombone section, just an incredible player and Trombone Shorty—he is amazing! That’s the kind of band I’m putting together.

LBW: I can’t say. I’d have to pick them out, I guess. Sometimes you put somebody else in there, they muck up my business. You muck me up, I ain’t hitting on nothin’. I just play myself, and I got a drummer. If I could have anything, it would be a bass guitar player and a drum, that’s all I need. My son plays bass, he can play lead, too. His name Leo Welch, Jr.. He’s watching me, and learning to play.

EM: If you only had one thing to listen to, what would it be?

LP: There’s this Korean massage shop and they play this piano that’s so soothing you can just lay there. That’s the kind of music I’d listen to, or some real great string quartet, no drums, no brass, no reeds, maybe an oboe, because to me nothing is like relaxing to some great soft music.

LBW: I believe I’d listen to Muddy Waters.

Be the first to comment!