By Jim Hynes

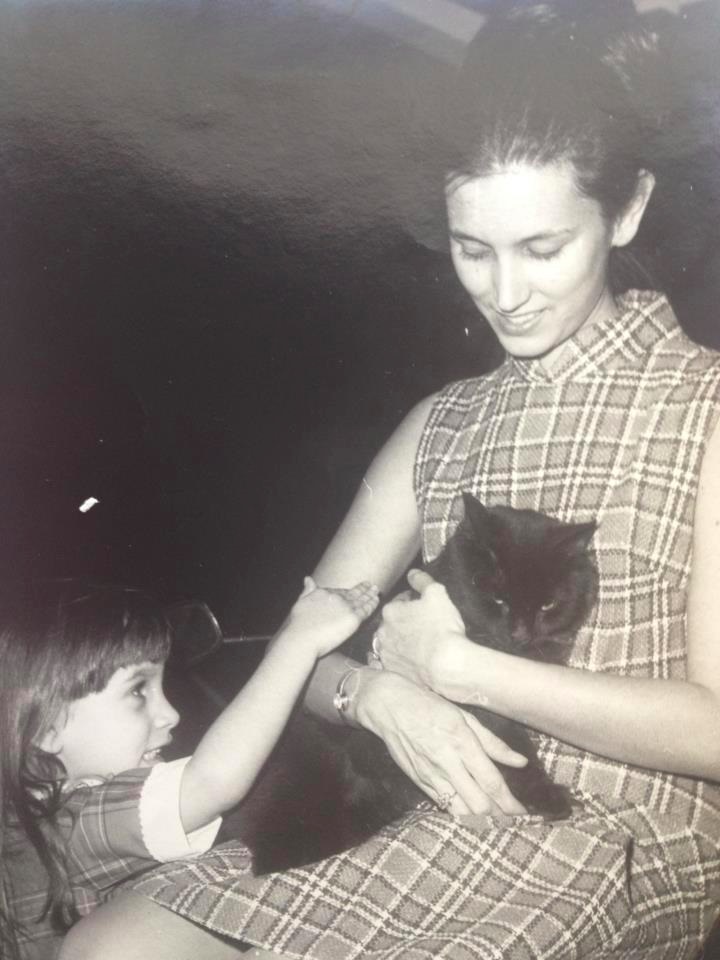

Heather West is a modest lady. More than once, she repeated to me that there are many, many individuals who have contributed more to “saving American music’’ than she has. Well Heather, we’ll be the judge of that. Over her multi-faceted career, she has built a reputation for having great taste in a widely diverse range of music styles. Growing up in the Live Music Capital of World, Austin, TX, and working for almost a decade in New Orleans– and even longer now in Chicago– she has played an instrumental role in helping artists and musical events gain exposure; all along the way, her career has taken her to some essential places.

[Editor’s Note: Much of our content here at Elmore Magazine is sourced directly from publicists like Heather. In fact, publicists make up a huge group of unsung, behind the scenes heroes doing their part to Save American Music. West is the first of many you’ll meet in the coming months for our series. Thank you Heather!]

Elmore Magazine: For our readers, if you were to draw up a job description of a publicist what would it look like?

Heather West: The job of the publicist is to gain exposure for bands, artists and festivals. We do that by cultivating media sources to get the name out there while also supporting tours by gaining press and appearances at community radio stations. The radio part means getting opportunities for artists to both play and be interviewed on-air, as well as placements on programs like NPR’s World Café, etc.

EM: What are the most rewarding aspects of being a publicist?

HW: For me, of course it’s always thrilling to see a piece, whether it’s an article or review, come out. That keeps you going day to day, but the overall, it’s watching an artist grow. As they grow, the hope is that you get them even better placements. The same applies to festivals… seeing happy fest-goers, knowing that you helped make some key decisions along the way that made the audience feel better. Sometimes it’s not just the music, it’s logistical and amenity decisions I may have shaped to result in a better audience experience.

EM: What are the biggest challenges?

HW: Competition. The advent of home recording and digital recording has made it much easier and feasible for artists to record their music. There are more releases now than there were even five years ago and with that, there are more and more publicists too.

EM: How do you “brand” your firm? Or said another way, how do you differentiate yourself from your competitors?

HW: I have never consciously tried to brand my company. I think I’ve become known as someone who has good tastes in music and will give an honest assessment. When I first started my company in 2009, many of my friends and others that I trusted in the business told me it was important that I establish a social media presence on Facebook and Twitter. And, they were right. So now I use an approach where 50% of my messaging is about an artist, some are mine and some are just those I find interesting in some way, and 50% is personal where I may share things about my family, my dog, or things that are piquing my interest. You know, 15 -20 years ago, maybe not even that long ago, it seemed like I was on the phone constantly. That has certainly changed, because so much is done through email now. Social media bridges that gap somehow. It brings back some of the personal touches you cannot get otherwise. People want to know if you have a sense of humor.

EM: How many clients do you have in a given year?

HW: It’s about 35-40 projects per year. Most are artists, but of course the Riot Fests in both Denver and Chicago are a major part of my work. I’ve also worked on some non-music projects like Red Bull and movies. [Editor’s Note: These are just some of West’s clients that we have covered in Elmore – Jimmy ‘Duck’ Holmes, Ruby Dee & The Snakehandlers, Colin Lake, Western Star, Tom Rhodes and numerous artists on Louisiana Red Hot Records.]

EM: You’ve had an amazing career in the music business. Let’s go back to the beginning. You grew up in Austin, TX. What are some of your earliest impressions from listening to music in your teens, or even earlier if it goes back that far?

HW: I’ve been surrounded by music my whole life. My dad played lots of records at home and took me to lots of shows. My stepfather played about 12 instruments. I can remember those first moments when music just moved me to the core- transported me to another place. Seeing Freddy King, Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen, Merle Haggard, soul music and amazing rock music… I remember Joe Ely opening for the Clash in my early teens and have significant memories of live shows going way back.

EM: While you were in Austin, you were the talent buyer at the famed Antone’s. What was happening at Antone’s then? What was Clifford Antone like?

HW: This was when we were booking Buddy Guy, Luther Allison, Otis Rush, Buckwheat, C.J Chenier, Earl King, Barbara Lynn… I could go on for hours. We started doing non-blues on Wednesday nights and would bring in rockabilly and Cajun bands, for example. We had the best house band around and artists would love to play with them. George Rains was on drums, Kaz Kazanoff on sax, Sarah Brown on bass, Derek O’Brien and Denny Freeman on guitar… sometimes Doug Sahm would stop by and play some amazing piano or guitar.

What I’d say about Clifford is that he was wonderful. Musicians loved him. He was one of the kindest people I’ve ever known. He would take a bullet for the men with special needs he had working at the club. I remember one time- as much as it pained him to sell one of his guitars- he just gave it to an enthusiastic kid that was about 18 years old. He used to be upset, when I was taking courses at Austin Community College, that I couldn’t join him for dinner, but he’d drive me to class and sure enough, at 9 o’clock when class was over he’d be in his car waiting to drive me home or back to work.

EM: Wow! You had so much incredible music in Austin, but you eventually left and relocated to New Orleans. Was that to attend college? Why did you leave?

HW: I moved to New Orleans in 1990 when I was 26. I enrolled at the University of New Orleans, but didn’t go there to go to school. I had many close friends who were living there and just loved the city. Still do. It’s sounds funny to say this now, because we’re talking 25 years ago, but even then I felt that Austin was getting too fancy. New Orleans was just funky and different and had lots of appeal. You look at Austin now, and it’s as if half the movie industry from LA has moved there. Anyway, at some point it’s good to leave home and get a new perspective, right?

EM: So you started working for one of my favorite record labels, Black Top. What were you doing for them?

HW: Initially, my role was undefined. I began by auditing their distributor statements which, believe it or not, they hadn’t been doing and saved them some considerable money right away. At the time they were affiliated with Rounder and were using those resources for publicity. I started doing radio promotion and gradually took on more responsibility; I was doing our manufacturing, bookkeeping, dealing with our distributor, hired independent radio promoters as we grew– a million tasks. I was General Manager of the label till we sold it. One of the best things I remember about Black Top was working with Maria Muldaur and Solomon Burke. They taught me so much about interviewing – mainly meaning that you need to use the interview to your advantage. If you don’t like the question, just politely compliment the interviewer on the question and then proceed to talk about what you want to talk about.

EM: So, next how did you get involved with the Ponderosa Stomp?

HW: It started with Kelly Keller, a former Black Top employee and close friend, who ran the Circle Bar, which was known for having the best jukebox anywhere. She and her partners were big fans of the artists we had on Black Top, and unsung heros of American music. Back then it was legal for cigarette companies to give money to bars and they also had digital gambling, otherwise, they would not have been able to afford to bring in live music, but with these resources they did. They transformed the bar into a club and then began to bring in artists like Barbara Lynn. Ira “Dr. Ike” Padnos and a lot of our friends formed the Mystic Knights of the Mau, a group dedicated to bringing back the legends of blues, R&B, rockabilly and swamp pop. We later had the Ponderosa Stomp, with a record fair, music conference, a standing exhibit at the Louisiana State Museum and then helped book shows at places like Lincoln Center and SXSW for these talented artists who may have had one or two hits but never really broke through in a big way. Once the Stomp got going as a major festival, I was too busy to do the publicity as well– I was already working 80 hour weeks. But it was around that time that I formed my own company, so then I had the time to take over publicity for the Fest. Worthy publicists like Cary Baker of Conqueroo and Matt Hanks from Shore Fire also helped with publicity.

EM: What prompted you to leave New Orleans for Chicago?

HW: I met my future husband at a radio convention in San Francisco. He lived in Chicago, had a son, and we began long distance dating. After we got engaged, I began commuting between Chicago and New Orleans. Eventually I moved to Chicago full time in 2001. I worked for two labels there, Bloodshot for two and half years and Victory Records, where I was National Publicist and had a staff of five people. I started my own company, Western Publicity, in 2009.

EM: You are in the midst of your busiest season, principally because you are the publicist for the Riot Fests taking place next month in Chicago and Denver. Tell us a bit about them.

HW: It started out as a punk rock festival in seven different venues in Chicago, but now it’s in one outdoor festival and held in Chicago, Denver and Toronto (although not this year). One of its hallmarks is reuniting bands that haven’t played together in a while, like the original Misfits this year. But it has progressed to much more than just a punk rock festival. We’ve had Joan Jett, Ice Cube, Merle Haggard and reggae bands, for example. The undercard features some really good bands beyond just the headliners. It’s the only large festival that I know of that does not have corporate backing from companies like Live Nation.

EM: You’ve seen plenty of changes in the music business, and you’ve certainly played an important role in keeping good solid roots music alive. What’s good about the music business today?

HW: What’s good for the consumer is the accessibility of music. Now you stream something to decide whether you want to buy it or not. On the other hand, streaming isn’t so good for the artists.

EM: If you could change one thing about the music business, what would it be?

HW: I’d love to restructure the way artists get paid. Self-releasing an album used to have a stigma. It usually meant that you weren’t worthy enough to have label backing. Now artists have found that self-releasing and self-financing is much better financially. The statutory rate for publishing has not gone up in 15 -20 years.

EM: Anything else you’d like to add?

HW: It’s an honor to do what I do.

I work with a lot of publicists. Heather is one of the best.