By Mike Cobb

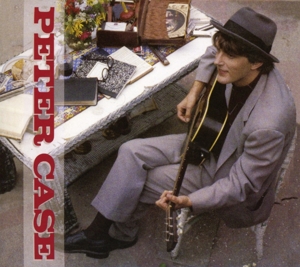

Peter Case is one of America’s greatest living singer/songwriters. In the early 1970s, he founded the seminal pre-punk band the Nerves, later went on to front the Plimsouls and, in the mid-80s, embarked on a fruitful solo career. He has worked with Sir George Martin, Elvis Costello, Mike Campbell (Tom Petty), David Hidalgo (Los Lobos), Ry Cooder, Roger McGuinn (the Byrds), Van Dyke Parks, Victoria Williams, John Hiatt and many more. His debut solo album, Peter Case, produced by T-Bone Burnett and Mitchell Froom, earned him his first Grammy nomination, and has just been re-released on vinyl by Omnivore Records.

Case will be performing live at Hill Country BBQ at Rockwood Music Hall in New York City on Friday, October 14th. For more information and tour dates, head to his website.

Elmore Magazine: How did you get started in music? Did you grow up in a musical household?

Peter Case: Yeah, I did. I was the youngest kid in the family. There were a bunch of teenagers in the house, and I was just a little kid. I grew up in a household with a lot of rock ‘n roll, and it was the ’50s. My big sister played boogie woogie and Fats Waller type piano, stride piano and she was pretty good at it. And so I grew up with a lot of that kind of the music in the house all the time. They started me on the piano, I quit, took up sax for a bit, and then eventually the guitar.

EM: Was there a crystallizing moment when you realized– this is what I want to do?

PC: Yeah, I guess I was about six, and I think it was my sister who said that I had an intense devotion to rock ‘n roll. We had all these singles at the house: Elvis, Chuck Berry, the Everly Brothers. So I really loved that, and then a few years later I got really into the Kingston Trio; they were really big, with Tom Dooley. I was just a little kid, man. My mother bought me a copy when we were shopping, she got these stamps you get for buying groceries, and you got a free record. And then I guess… I wrote my first song in about ’65 when I was 11; it was right around then when I got really serious about it. I’m from Buffalo where everyone wants to play football, but I got real serious when I was about 14, I had a band and we were working around town. I was playing firehouses, dances, youth centers, high school dances, solo at coffee houses, church basements. You’d just pick out what kind of gigs you could. I did that for a couple of years, one band got pretty popular, and then I joined up with some older guys up in Buffalo who were playing blues. They were in their mid-20s, and I learned a lot from those people. I was also doing a solo thing all along, and then I grabbed the guitar and went to California when I was 18, y’know? I left home at the end of my 15th year and moved in with a bunch of musicians.

EM: In the late 70s, you founded the Nerves with Paul Collins in San Francisco. Can you describe the scene back then?

PC: Actually, I moved there in ‘73, then the Nerves started at the end of ‘74, we started playing SF in ‘75, made our record in ‘76, and the on the very 1st day of ‘77 we moved to LA.

EM: I know, that was all during the growth of what we now call “punk rock.”

PC: Well, we were previous to punk rock. We weren’t really an outgrowth of the punk rock movement, and we were never really a punk band, but when punk rock arose, we felt sympathy with it, y’know? Because we were kind of in opposition to our peers in the music world, and we were very different, also playing very fast, so there was a punkish element, but we actually started in late ‘74, so it was that very first blast of rock ‘n roll from younger people, and that’s really what punk rock was, like a new generation of rock ‘n roll. But we were really before punk. I booked the first punk rock shows in LA. Do you know about that?

EM: Umm, well, no. Tell me!

PC: Well, you can read about it in the latest issue of Ugly Things. Do you know that magazine?

EM: No, but now I’m glad to.

PC: If you’re a rock ‘n roll fan, you’d really enjoy it. It’s all about garage rock and punk rock. It’s put out by this guy down in San Diego named Mike Stacks, and he gets a lot of great interviews with people all the time. In the latest issue, there’s a story in there about the start of the Weirdos and punk rock in LA and how I came in and convinced these guys to play a gig with us before they had a drummer! And so we were finding the Germs, the Weirdos, the Zeros, the Dils, all those bands played their first gig with us. And we had a few bucks from San Fran, so we came down to southern California and booked out a hall or two and put on these shows. The Whiskey wasn’t putting on young bands, we couldn’t get booked, so we booked our own shows and affiliated with all these punk rock bands who were just starting. They all played with us, and then we went on tour with the Ramones, also solo, and we played with Pere Ubu, and Devo, before they had record deals, and then that band exhausted itself by early ‘78, but it was kind of ahead of the curve.

You know what they say, the early bird doesn’t get the worm, it’s the second bird. I think Guy Clark used to say that. It’s kind of true. [Laughs] We didn’t get the worm, man. Though one of those guys from the Nerves made a lot of money off of that song “Hanging On The Telephone,” y’know– the guitar player.

EM: Next came the Plimsouls. Tell me about that.

PC: So the Plimsouls…the vision of the Nerves was a band where everything was minimal. I was really getting it together in the Nerves, but the songs were really stripped down, they were like two minutes long. With the Plimsouls the whole thing got fleshed out; we were more of a live act. As a result, the band went over pretty well, live, everywhere. So we’ve always been known more as a live act. In fact, my favorite records by the Plimsouls are the three live records that have come out from back then. There’s one called One Night In America from ‘80-81, another called Live: Beg, Borrow, & Steal at the Whiskey A Go Go from ‘82, and then there’s Beachtown Confidential from ‘83 from the Huntington Bear. And those are my three favorite ones; to me those are better than our studio records. The band never did really get comfortable in the studio.

EM: They didn’t quite capture what the band was truly about?

PC: The live things did. We were breaking attendance records live in California. We had a big record on the radio, A Million Miles Away, but it never seemed like it got produced correctly. Maybe even the Nerves were produced better in a way. But the Plimsouls made their reputation as a live band, so that’s fine with me.

My songwriting was evolving from writing these two minute songs I’d been performing solo since I was 15 or 16. Towards the end of the Plimsouls I started writing these other kind of songs that were songs you could play completely solo; a lot of my favorite music has always been like blues singers like Robert Johnson or Lightnin’ Hopkins that could bring the whole picture to you just solo– really exciting, rocking music, not any esoteric thing, just done by one person.

When I was a kid, I hitchhiked over to Boston from Buffalo– which is about 600-700 miles– and I saw play Lightnin’ Hopkins play over there. It was early ‘71. I went over there in a blizzard, man. It took me a few days to get over there; I actually wrote a story about it. It was incredible man; it was, like, really moving. So I always carry that in my mind. Actually, there’s a song that I do based on some Lightnin’ Hopkins music on that solo record [Omnivore’s reissue of Peter Case] that just came out.

EM: Excellent, looking forward to hearing that. Since departing from the Plimsouls, you’ve moved in an increasingly acoustic direction. Why is that? I imagine it’s easier than dealing with band dynamics and all that.

PC: Yes and no. Easier is a strangely relative term. Going out and playing solo is rigorous in its own way, because it’s all down to you, y’know? So to keep doing it, you have to bring it up to a certain level where people are getting off on it enough that it’s worth doing.

I haven’t been increasingly acoustic. You’re either acoustic or you’re not. I go back and forth between all those things. It’s more about the song than whether you’re acoustic or not, though I do like acoustic music. But I like rock ‘n roll too. I love full on rock ‘n roll, and I believe you can play acoustic rock ‘n roll like Jonathan Richman did, or like I do too. All those boundaries and borders and definitions in music are not as interesting to me as whether something moves me and gets me off. And so, I don’t just like genres of music. I love Bob Dylan, Townes Van Zandt, Bert Jansch, those guys all played solo acoustic, but I don’t like everybody who plays acoustic music. And I like all their electric music too. A lot of different musicians play electric and acoustic, and I’m that way too. It depends on the situation; you have to make up your mind. I tour a lot solo, and I do like it. I like the freedom of it, the contact with the audience, and I just like the freedom to be out there and put everything into the song as opposed to having to rely on an arrangement. I just like putting everything into that one performance. They’re kind of like movies that you project on people’s imaginations, y’know? If you do it right, you can take people to a whole other place that can almost feel like a whole big orchestra. It’s possible to put it all into a real simple approach. I’m into songs and singers, y’know?

EM: I’m a singer/songwriter too. For me, playing solo often feels very naked. There’s not much room to hide. Do you feel that way as well?

PC: Well, certainly when I first started doing it, after being in bands for many years, I felt really exposed. But I’ve come to love that. Over the years I’ve learned to put a lot more into it. When I first came out of bands it was kind of shocking, kind of like a cat being thrown into cold water, y’know? (Laughs) But if the songs are really right, and you’ve worked on it right, it can go to a whole other place where you don’t have to suffer like that. But I know what you mean, I especially felt like that when I came out of the Plimsouls.

EM: Your first solo album was produced by T-Bone Burnett and Mitchell Froom and had quite a roster, including Victoria Williams, Mike Campbell, John Hiatt, Jim Keltner, Roger McGuinn, Van Dyke Parks and many others. How did you assemble that crew?

EM: Your first solo album was produced by T-Bone Burnett and Mitchell Froom and had quite a roster, including Victoria Williams, Mike Campbell, John Hiatt, Jim Keltner, Roger McGuinn, Van Dyke Parks and many others. How did you assemble that crew?

PC: Well, me and Victoria were married, so she had to! [Laughs] No… she didn’t have to, but she did. We were up picking guitars one night; it was me, Elvis Costello, who writes about it in his new book, T-Bone, and Bob Neuwirth. Elvis played me “Pair of Brown Eyes.” It was a single off the new Pogues record. We were all playing our new songs for each other. I’d never heard it or any of Shane’s [McGowan] songs, and I really dug it. We started talking about it, and I said we should do what the Byrds did with Bob Dylan. We could take that song by the Pogues and electrify it. We put together pretty much the same band as the Byrds used on 5D. Van Dyke Parks, who played organ, and Roger McGuinn is on it. It’s sort of electrified and expanded, sort of a far out version of the song. T-Bone asked who I wanted to work with, and I said Van Dyke Parks, I’ve been a fan of his since I was kid. We had Song Cycle and Discover America. I also loved all the work he’d done with other people; he also played on that record with Judy Collins and Stephen Stills, Who Knows Where The Time Goes. Anyway, it was fantastic working with him. He put a string quartet on “Small Town Spree”; I got to take a harmonica solo on that, if you can imagine that. It was super fun; it was a joy.

The idea on the first record was folk music, like Appalachia, but with a groove to it. So you really feel it. That was the vision for that record. The track “Three Days Straight” has Victoria on it with a drummer named Jerry Marotta.

EM: I know there’s some extra tracks on it. Can you tell me about that?

PC: There’s seven extra tracks. Several of them are from the original recordings we did in Fort Worth from ‘85 that I did with T-Bone. Some of them are the same songs but done radically different. There’s an outtake song called “The Toughest Gang In Town,” with stacks of harmony vocals from Marshall Crenshaw, who is a friend of mine. It really sounds great. One of the best songs on there, I don’t know why we didn’t put it on the record, is called “Trusted Friend.” It’s a good song and we did get a really nice recording of it.

EM: What informs your songwriting?

PC: My heroes when I was a kid were solo blues singers and poets, especially the Beat poets. And for a while there I really wanted to be a big rock ‘n roll star when I was with the Plimsouls. But before that my heroes wrote and represented life. I like all kinds of stuff like that. Obviously it feeds your mind if you’re writing; it opens up your mind. If you don’t read books it limits you. You gotta read, man. I get the feeling that a lot of country singers these days don’t even read. [Laughs] I mean at least Hank Williams read the bible, man. You gotta get all that experience. You go and get real experience from the world, live, talk to people and read! That’s how I see it. And you gotta know the history of music, listen to the old stuff and get over the hiss in old records. If you do that, then you’re on the right track. [Laughs]

EM: How does the songwriting process work for you? Where does inspiration come from these days?

PC: Well, I don’t know man. Inspiration’s the big one. There’s no point in doing anything if it’s not inspired. Inspiration’s the only really important part of it. Where does it come from? You never know where the next thing’s gonna start, so you can’t really plan for it. Things just happen. A lot of it’s just based on your life. That’s why I stay on the road a lot. In a way it’s inspiring to be out seeing and meeting people, playing for a different audience every night and traveling. I find that inspiring because it sets you up for things that are unexpected, and when unexpected things happen, that allows things into your mind. A song will come in through that window.

Craft is different; it’s not really a compliment. It’s sneaky, crafty. What you want is something that takes people away, that has an incredible vibe to it. It’s mysterious. You’re always looking for that thing that’s more than you are or more than we all are. It comes from a window or from outside; it’s not just mundane. You never really know where the next thing’s gonna start.

EM: Your career has spanned all kind of different scenes, moments in history, analogue to digital. What’s different today than when you first started out?

PC: Music today has a much less important place in society. It was looked at in a different way in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Now it’s just part of all the options that people have. But music’s really prevalent anyhow. A lot more people want to have an authentic relationship with music than they used to. It used to be that I was the only kid who played guitar at school. Now everybody plays, or they’re a DJ or something. So it’s very different. In a way that’s good, that’s interesting. On the other hand, there’s less people who are really committed to the history of it. You gotta know the history and know what’s been done to know what’s left to be done. And you need to know the old stuff. These days people know less about the past; it’s more homogenized.

EM: Do you think the transition from records to CDs to digital downloads has affected people’s relationship to music? Clearly an mp3 is not the same as holding a record in your hand, but there’s been a resurgence of vinyl, which I hope helps people connect more again.

PC: Yeah, like streaming. They don’t pay the artist, which is a huge demotion, but on the other hand you’re able to hear more. But it’s possible that you hear more but have less of a relationship to it. I remember when I was a kid I had one Bob Dylan record, Bringing It All Back Home, and I used to listen to it like a million times. I had like about 10 records. You learned them so much, you knew everything about it. That’s a very deep relationship to music. I guess that’s still happening, but you have to create that yourself. But like they say, you can have incredible access but no context.

This is an excerpt of a larger phone conversation, recorded in September. To listen to the full interview, head over to Mike’s Mixcloud page here.

Be the first to comment!