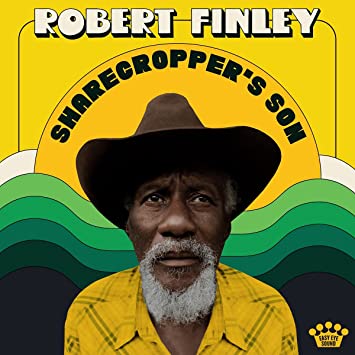

Artist: Robert Finley

Album: Sharecropper’s Son

Label: Easy Eye Sounds

Release Date: 5.15.21

When Robert Finley first walked into Easy Eye Sound in Nashville, studio owner Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys fell right out of his chair. Finley’s leather pants cinched with a huge Western belt buckle, his snakeskin boots, leather cowboy hat, three-quarter-length leather duster, and folding cane that the legally blind singer wore on his hip, in a holster, presented a man striking in style. But when Finley sings, it places him in a completely different, singular category. Robert Finley’s emotion comes straight from the gut, the heart, and the soul, no sign whatsoever of that exterior flash. Auerbach cites Finley as the greatest living soul singer, an assertion validated ten times over on Sharecropper’s Son.

Robert Finley was born and still resides in small-town Louisiana. He bought his first guitar as an eleven year-old, using the twenty bucks his mother gave him for shoes. In the Army at 17, he played in the band, enlightening fellow soldiers to the virtues of the blues and soul music. Once discharged, he busked in hopes of a career, but economics demanded that he land a job as a carpenter. But when Finley began losing his sight ten years ago in his late ‘50s, he resumed following his dream. Sharecropper’s Son is his third album, and the second one that Auerbach’s produced. His first two were eye and ear-opening treats. This one’s a stone-cold killer.

The instant Finley croaks the words “Souled out on you,” and as pianist Bobby Wood plays regal little couplets around him, the album proves spellbinding. Finley moves from a cracked falsetto of frustration into gritty, fed-up determination with natural, melodic ease. His animation, carried by a flavorful, full band performance, drive his points like spikes to the heart of the matter. Auerbach gathered a crew of players that like him, know Finley’s story. And it’s a series of those stories that Finley couldn’t hold inside any longer, that make this album so special. For several, he even made the lyrics up on the spot, as the band played along, and the tape rolled. He calls it speaking his mind, straight from his soul. I call it astounding.

Spooky, swampy melodies envelop “Sharecropper’s Son,” Finley’s recollections of his early childhood. As he sings “Never had time for playin’, never got to have no fun…out in the red hot sun, because the work was never done,” Finley nails the definition of real blues because he was there, obvious by his urgent delivery. But Finley believed, and he persevered. Inside the raw, bumpy, hill country rumble of “Country Child,” he relates how as a young man, he tolerated living in the city, in a messed-up world. The effects of that are startling. But then, as if a huge flag unfurls, “My Story” opens up wide and celebrates success, gratitude, and possibility with grand, glorious waves of soul. Finley’s proclamation that “We’ve got to teach our children how to fly, so they can reach those stars in the sky” could prove as life-changing for others, as it was for him.

Otherwise, 1970s-era soul music pops in “Starting to See,” Finley’s song about true love realized. And in “Make Me Feel Alright,” he illustrates through tough-rocking music and words how a man’s need to utilize the oldest profession in the world can make you feel alright too. But ultimately, it all comes back to the gospel truth. “All My Hope” closes the album with Finley thanking his Lord for all his virtues, and for getting him through. Sharecropper’s Son has it all— extraordinary songs and singing, robust and exciting musical accompaniment, and an overall presentation that makes a difference in more ways than one.

—Tom Clarke

Be the first to comment!