I have a habit sometimes of buying albums, listening to them once, and then relegating them to a shelf for upwards of ten years or more.

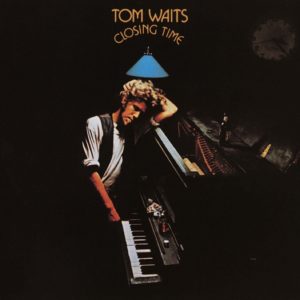

I’m ashamed to admit it, but that’s what happened with Tom Waits’ 1973 debut album, Closing Time. I bought it in Little Neck as a teenager, plugged it in once, and then set about forgetting how good it was.

I hope Waits will forgive me. After all, he’s been one of my all-time favorite musicians since high school, back when a friend lent me a copy of Small Change to check out. In my freshman year at Binghamton University, I’d always enjoy trying to replicate Waits’ look and sound by donning a newsboy cap and ripping my throat apart during open mic nights. I’d tear into the six-minute “Step Right Up,” sometimes accompanied by an upright bassist, sometimes solo, always trying not to lose my place in the tune’s near 800-word count.

I enjoy Waits in all his permutations – the jazzy beatnik reeking of blues and cigarette smoke circa 1976; the Bertolt Brecht wannabe in suspenders, enveloped in marimbas throughout the Reagan era; the 21st century Mad Hatter constantly turning sounds and genres into a kaleidoscope of craziness.

But there was one type of Waits I wasn’t prepared for– folksy singer/songwriter. This was before unkempt suits, Rickie Lee Jones, soundtrack work, Kathleen Brennan and macabre inclinations all shifted his discography into something still wonderfully anomalous by today’s standards.

Though Waits wouldn’t release a “live” album until two years later, with Nighthawks at the Diner, each of Closing Time’s songs have a live feel to them. They could fit right in with Birdland or a Village Vanguard in terms of dynamic and atmosphere. You can envision the clinking glasses, the haze of smoke, the dim bulbs hanging overhead.

Arguably, Closing Time could be Waits’ most accessible album. He’s not barking. His vocal rasp is there, but in a much more subdued manner. Unlike its title, Waits is open to being appreciated, because from here, if you’re not familiar with his canon, you’re in for quite the roller coaster ride of creativity.

Arguably, Closing Time could be Waits’ most accessible album. He’s not barking. His vocal rasp is there, but in a much more subdued manner. Unlike its title, Waits is open to being appreciated, because from here, if you’re not familiar with his canon, you’re in for quite the roller coaster ride of creativity.

Closing Time opens with “Ol 55,” a wistful number that’s almost sad in its terrific delivery; it’s the kind of song you could envision Harry Nilsson singing in the “Without You” vein. There’s no screaming, no double entendres – just a 23 year-old, longhaired kid trying to make it big.

“I Hope That I Don’t Fall in Love With You” is based primarily around an acoustic guitar as Waits croons along with his pluckings. You hear the muted trumpet on “Virginia Avenue,” and you’re suddenly transported from 1973 to 1943, the Maltese Falcon days of fedoras and uncertainty. Hard to believe this is the same guy who would later scare the bejesus out of us with future numbers like “Red Shoes by the Drugstore,” “Hell Broke Luce” and “16 Shells from a Thirty-Ought-Six.”

“Old Shoes (And Picture Postcards)” can best be considered country and western. Same with “Rosie.” One highlight to pay attention to is “Martha,” played on an out-of-tune piano (he’s already bending convention), but fast on its way to becoming one of Waits’ most-covered tunes. It’s a Tin Pan Alley standard, and establishes a sound Waits would revisit frequently over the years. Listen to this and then immediately follow it up with “Johnsburg, Illinois” from 1983 and “Coney Island Baby” from 2002.

Only Waits plinking along at an out-of-tune piano can make something pleasing to the ear. That’s why “Lonely” is an album highlight, while “Ice Cream Man” is a fun treat, perfect for a little soft-shoe. The album also establishes Waits’ ear for instrumentals as its eponymous closing track is a longing melody that beautifully lingers in the air, even after silence takes hold.

In the time it took for me to listen to this album once and then a second time, Waits had already released eight studio albums, including some of the most critically acclaimed music of his career.

I have no excuse…

-Ira Kantor

Dig the column? Reach out to Ira via email at ikantor84@gmail.com or on Twitter at @ira_kantor

Be the first to comment!